Romance has long been associated with a wide range of often exotic locations, but the literature I explore in this article makes the most homely of domestic spaces – the kitchen – integral to the plot construction. The literature published in popular Pakistani Urdu[1] magazines, called “digests” by the consumers, is mostly comprised of plot-driven narratives. Previous scholarship on women’s digests in Pakistan is restricted to questions of female emancipation, patriarchy, and regional politics, overlooking the multilayered digest fiction. This research contributes to ongoing literary-critical debates on women’s digests through an [End Page 1] investigation of this distinctive national variety of fiction that is predominantly romantic in nature and offers insights into the reading culture of the country. I use the term “kitchen literature” to describe the fiction published in three popular digests in the country, the monthly Shuaa, Kiran and Khawateen Digest. The multi-layered digest fiction covers myriad social, psychological, and domestic themes including child abuse, domestic violence, trauma, and feminism. Some authors utilize romance plots of courtship and marriage to comment on social issues, but most popular narratives are celebrations of heterosexual love within the boundaries defined by patriarchal Pakistani society.

Kitchen literature is an appropriate term for this fiction because the kitchen is a space strongly associated with Pakistani digests and their readers in every city. This space has particular significance in the predominantly patriarchal Pakistani society as a site that defines gender roles in the upper- and lower-middle classes. Moreover, the kitchen is a frequently used setting in digest fiction, regardless of its theme. I examine the fiction printed in the Shuaaa, Kiran, and Khawateen digests between the years 2001 to 2018. I have limited my research sample to a randomly selected fifty love stories, and confine my analysis to the diegetic and extra-diegetic roles of the kitchen, and the interconnection of these roles.

There are a number of important precedents for labelling a national variety of popular fiction “kitchen literature.” There was, for instance, a genre cycle in the United Kingdom in the mid-twentieth century which was titled “kitchen sink drama” (Dornan). Kitchen sink drama had a leftist ideological stance and focused on the portrayal of people who struggled against the “degradation of powerlessness, the loss of community, or the deadening influence of suburbia” (Dornan 452). More pertinently for my research, the term “kitchen literature” has been used in connection with the genre of sensation fiction, which became popular in the 1860s (Hughes; Steere; Bernstein; King). Studies of sensation fiction frequently refer to an 1865 article in North British Review by William Fraser Rae, which designates the novels of Mary Braddon “as the least valuable among works of fiction” and “literature of the kitchen” (Rae 203-204). Rae maintains that Braddon’s stories are favoured by readers who are “the lowest in the social scale, as well as in mental capacity” (204). Sensation fiction readers, at the bottom of the social scale, are “scullions” who prefer reading about “[t]hugs,” “murderers” and “detectives” (202). Rae further interprets the inferior literary taste of sensation fiction readers higher on the social scale as a symptom of low mental capacity (204). Elizabeth Steere notes that after the publication of Rae’s review, several other publications started using kitchen literature as a derisive term for an emerging reading culture in which “the sensation novels that the cook or maid would read were now being read by the mistress of the house as well” (1).

Besides the important difference in genre and themes, my usage of the term is neither derisive nor limited. I define the nuanced fiction of Pakistani women’s digests as kitchen literature because the kitchen is the favoured reading space of the majority of the middle-class readers living in cities. It is an empowering space for the readers as they can exercise control there and have some moments of privacy. The urban domestic setting is diegetically important for the characters’ declarations of love, because the readers can relate to it, and it constitutes the romantic chronotope that distinguishes this brand of fiction.

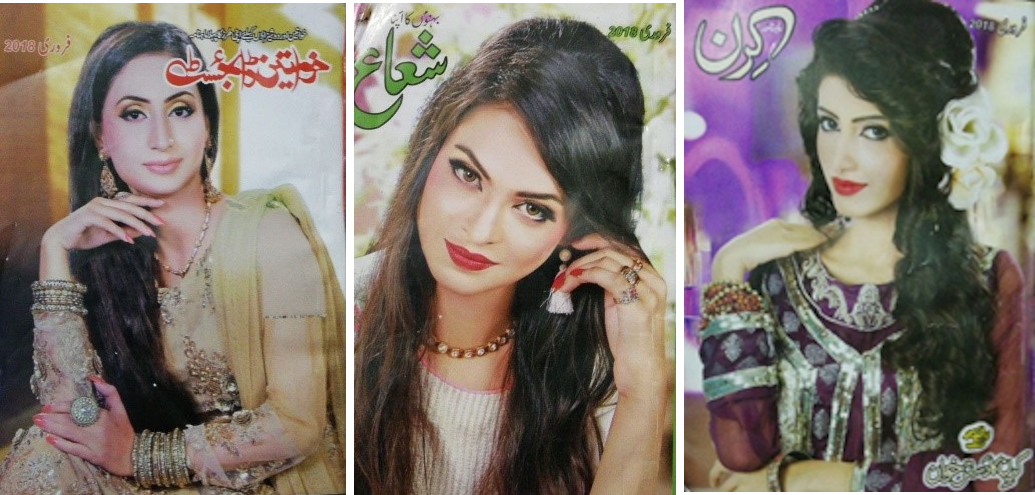

Kitchen literature is central to a “genre world” designed by and for middle-class Pakistani homemakers. Lisa Fletcher, Beth Driscoll, and Kim Wilkins explain that a “genre world” is a “collective activity that goes into the creation and circulation of genre texts, and is particularly focused on the communities, collaborations, and industrial pressures that [End Page 2] derive and are driven by the processes of these socio-artistic formations” (2). Shuaa, Kiran and Khawateen Digest (see fig.1) are more popular than other women’s digests such as Pakeeza and Anchal (Hassan), a fact that becomes more interesting when you realize that all three of them are printed by one publishing house: Azar Publishers. In Urdu, Shuaa means “ray of sun,” Kiran means “sunshine” and Khawateen means “women.” Shuaa and Khawateen Digest have subtitles that declare them to be “Sisters/Women’s Own Monthly Magazines,” which constructs a bond between the readers and the texts by evoking, to quote Janice Winship, “the ‘we women’ feeling” (77). The female camaraderie of editors, authors, and readers the kind of “a dynamic real-and-imagined sociality” (Fletcher et al. 2) typical of romance genre worlds. This existence of an “imagined sociality” is strengthened by the use of editorial we and possessive ours, in the non-fiction sections of the digests.

The digests share a common format. They measure approximately 8×6 inches, have a coloured cover and include 290 black-and-white pages. The physical design of the digests is highly reflective of the reading habits of their target readers: mostly middle-class homemakers with an average education, who usually keep the digests in their kitchen. The position of the kitchen as the favoured reading space of the digest readers is supported by my own observations and reading experiences, and by surveys published in the digests, which include readers’ comments on their favourite authors and reading habits. For example, the segment “Journey of Bright Moments” in a randomly selected sample of Shuaa includes reader Anila’s experience of making biryani rice while reading the digest, which she had conveniently placed on a kitchen shelf (Editorial Board 18-19). Another reader burned her roti because she was engrossed in reading her favourite author Misbah Ali (Editorial Board 24-25). The black and white pages of Shuaa, Khawateen Digest and Kiran contain, in exact order, inspirational/religious quotations, celebrity/author interviews, an episode from a serialized novel, a novella, several short stories, reader’s letters, celebrity gossip and beauty tips. In the past, serialized novels were based on everyday family issues, marriage politics and romance, but for the past ten years, thrillers such as Umera Ahmed’s Aks (Reflection) (2011), Nimra Ahmed’s Jannat key Pattey (Leaves of Heaven) (2012) and her blockbuster Namal (2014) have completely taken over this space. Such serialized thrillers garner an enormous national and diasporic fan following, which grows when they are printed after their serialization as stand-alone hardcover novels. However, a discussion of thrillers or another subgenre of fiction in the popular Urdu digests falls outside the scope of this paper, which focuses only on the construction of romantic chronotopes in the love stories. [End Page 3]

While there is relatively little research on fiction published in women’s magazines, in her 1963 classic study The Feminine Mystique, Betty Friedan does discuss the evolution of the heroine of American magazine fiction. She explains that fiction written for magazines in the US before the 1950s featured independent, confident and career-oriented heroines. This type of heroine was replaced after the 1950s by the “happy housewife heroine,” who Friedan interprets as the embodiment of a “feminine mystique” that celebrates the housewife-mother as the role model for all women and glorifies the “passivity implicit in their sexual nature” (43, 58-59). She explains that “serious fiction writers” eventually disappeared altogether from women’s magazines and “fiction of any quality was almost completely replaced by a different kind of article” focused on domestic details ranging from “the color of walls or lipstick, [to] the exact temperature of the oven” (55-56). Friedan’s critique centres on the development of the feminine mystique for American women by the society as a whole and the way it has been portrayed in women’s magazines. Closer to the issues of my study is the sociological content analysis conducted by Cornelia Butler Flora of 202 examples of women’s magazine fiction published in the United States and Latin America. Her findings are that, across her corpus, the “female, because of her sex, is rewarded for passive behaviour. Few models of females actively controlling their own lives were presented positively in any of the fiction examined” (443). Similarly, Carmen Rosa Caldas-Coulthard argues that the first-person stories, published in US women’s magazines in the 1990s such as Marie Claire, Cosmopolitan and New Woman, are a blatant reaffirmation of traditional views of female sexuality and emancipation: “Through evaluative structures that link positive images to ideas of inadequate and insecure women, these texts put an emphasis on the themes of social asymmetries. Transgressive pleasure and social punishment are closely associated” (251). These analyses of magazine fiction intended for American middle-class women focus primarily on the representations of female characters and home-and-hearth settings and have little to say about the dominant genre of romance, or, indeed about magazine fiction in non-Western markets. For the most part, fiction is absent from or marginalized in [End Page 4] Anglophonic women’s magazines, which accounts for lack of attention to fiction in recent studies.

Fiction remains central to Pakistani women’s magazines but, surprisingly, the few extant studies follow the lead of Western scholars and have little to say about fiction. Studies of women’s digests in Pakistan are mostly sociocultural in nature, and describe a middle-class reading culture that advocates passivity in women by depicting, to use Friedan’s term, “house-wife heroines (38).” Kamran Asdar Ali’s article “Pulp Fictions: Reading Pakistani Domesticity” is by far the most comprehensive analysis to date of fiction printed in Pakistani women’s magazines. Ali offers a definition of the distinctive national variety of popular fiction published in magazines:

These Urdu magazines, known commonly as digests, contain a specific genre of short stories that are considered far below the highbrow literary production of more established yet less commercially successful literary journals. The closest translation of these narratives into a European-American idiom would be to compare them with Harlequin romances or television soaps (123-24).

Ali maintains, however, that a comparison with Anglophonic popular romances is not adequate for comprehensive analysis of the form, which can be traced back to Pakistani women-oriented narratives of the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries. He provides a brief literary history of magazine fiction, locating its origins in the oral tradition of women’s storytelling and distinguishing it from reformist literature in colonial India, which flourished after the independence of Pakistan and India and produced high-culture literature on tabooed themes like homoeroticism, inter-religious romance, and antipatriarchal politics (124-27). Ali analyses two stories, which he reads in relation to the culture and politics of Pakistan in the 1990s, and concludes, “[w]here early-twentieth-century reformist literature had its overt pedagogical task, the digests are a more fluid and complex genre” (140). While Ali’s claims for the distinctiveness of contemporary digest fiction informs my conceptualization of kitchen literature, he does not comment in detail on the centrality of domestic settings or the genre conventions of romance.

Shirin Zubair uses a case study conducted in a rural area of Pakistan to analyse various literacy practices of local women, including reading popular fiction. She comments that in the rural Siraiki area where she conducted her research, “younger and middle-aged women are generally more interested in romantic fiction and women’s magazines” whereas older women like to read newspapers (Zubair, “Qualitative Methods” 89-90). She does not, however, consider digest fiction in any detail. Instead, her research focuses on the role of the patriarchy in literacy and identity formation in rural Pakistani women. In a later article, “ ‘Not Easily Put-Downable’: Magazine Representations and Muslim Women’s Identities in Southern Punjab, Pakistan,” she turns her attention to women’s magazines in Pakistan, drawing heavily on Joke Hermes’ Reading Women’s Magazines and Janice Radway’s Reading the Romance: Women, Patriarchy and Popular Literature. Treating magazines as semiotic and linguistic constructs, Zubair argues that “even within a patriarchal Muslim society like Pakistan, there are subcategories of age, social class, education, and occupation that shape women’s identities and reading practices” (177). Curiously, she does not differentiate between fiction-based titles (such as Shuaa or Khawateen Digest) and magazines that contain no fiction (including Women’s Own, Mag, and She). This oversight may be explained by her [End Page 5] own lack of interest in the genre: “I am not a reader of these popular women’s magazines, which have a particular kind of readership” (178). According to Zubair’s content analysis of Shuaa and Khawateen, they contain 72 % fiction, which she reads as evidence that the digests offer a utopian world of romance to subjugated female readers in rural culture (187-89).

Nadia Siddiqui’s research is also conducted from the perspective of a non-reader of digests. She compares fiction in Pakistani digests with women’s magazine fiction in other countries (“Women’s Magazines”), and discusses the theme of matrimony, which she argues weaves together romance and traditional Islamic values (“Who Reads Urdu”). She categorizes digest readers into regular, less regular, and non-readers and attempts to “provide evidence if reading digests has any influence on readers by comparing them with the beliefs, choices and practices of the people who do not read” (“Who Reads Urdu”). She contends that, in general, digests aim to reform women according to Muslim ideals and thus adopt an educational approach. Women read magazine romances because they provide a “guilty pleasure” (“Who Reads Urdu” 9), which is difficult to obtain in their highly patriarchal society.

In contrast to Siddiqui, Ali refuses to label the digest genre fiction as “reformist literature” or to condemn their reading as vicarious pleasure (140). He writes that the popular narratives in the digests “represent local histories in a global moment, as these localized stories become afflicted by cosmopolitan scripts that influence domestic life along with other social processes in Pakistan” (141). Similarly, my research employs the term kitchen literature to describe digest fiction because of the extra-diegetic position of the kitchen as the physical space where the women read the digests while intermittently stirring the curry pot. This genre fiction explores complex, and controversial, themes of domestic violence, child abuse, female emancipation, and gender politics. Romance subplots often penetrate social commentaries in the form of happy endings: caring lovers for survivors of abuse, husbands who fall in love with their financially independent wives, and so on. However, newer forms of bildungsroman are emerging after the year 2016, which do not follow this reward trajectory of romance. In “Traveler on the Road of Passion”, Sumaira Hameed recounts the innumerable struggles of the self-made, unmarried, young woman Deena, who achieves professional rather than romantic success. I confine my analysis to the significance of kitchen as a space and place of romance, while opening the way for future studies of the multidimensional genre world of kitchen literature.

An analysis of romance narratives in kitchen literature shows that in most of these texts, romantic chronotopes are formed through the space of the kitchen and the time of love. Mikhail Mikhailovich Bakhtin adopted the term chronotope from the field of mathematics, where it functions as an introduction to Einstein’s theory of relativity. However, Bakhtin states that his use of the term is metaphorical in nature and that he is concerned with it only as a “formally constituted category of literature,” which points out the inherent connection between time and space:

In the literary artistic chronotope, spatial and temporal indicators are fused into one carefully thought out, concrete whole. Time, as it were, thickens, takes on flesh, becomes artistically visible; likewise, space becomes charged and responsive to movements of time, plot and history (84).

[End Page 6] Bakhtin uses his conceptualization of the chronotope to define genres and sub-genres and traces the rise of novel back to the Greeks. However, the Greek chronotope “enters adventure-time and a foreign (but not alien) country” (97), but the romantic chronotope in kitchen literature enters the familiar space of the kitchen and changes that space into an emotionally, romantically, and culturally charged place. The kitchen is not only the space where the essential union between the lovers takes place but also the extra-diegetic space where romance is usually read. The temporal markers in this chronotope are the declaration or acceptance of love, verses from some popular song, short poems and romantic wordplay. The short poems are either extracts from a popular, romantic poetic work or they are composed by the authors of the stories. These poems are usually placed at the beginning or the end of a meeting scene. For example, the first scene of Rehana Aftab’s “Let Me Live” takes place in the kitchen where the heroine, Samaviya, is busy cooking. The hero, Awaiz, enters, reciting poetry and asking for love:

“Heard that you lost your heart in the gamble of love,

This love will kill you, O Lover; you are still like a flower.

Samaviya please, fall in love with me.”

She had just finished making the lunch and was cutting salad now. Small beads of perspiration were glistening on her beautiful face. Stray tendrils of her curly hair were annoying her constantly, defying her efforts to push them back.

She was startled when she heard Awaiz in the doorway. Her hands, busy in slicing cucumbers on the cutting board, stilled for a split second. Then she took a rather long breath, shook her head disapprovingly at Awaiz and resumed working (Aftab 59-60).[2]

The analogy of a fragile flower has clear sexual undertones that are emphasized in a later scene when Awaiz wants to “absorb her fragrance deep inside him” (90). This opening scene sets the tone for the entire short story, which tells of Awaiz’s efforts to convince Samaviya, his parents and society more generally, of his love that is considered a taboo by all because of the age difference between them. Through the poem, Awaiz asserts that even though Samaviya is older than him, she is “still like a flower” to him. Three out of four of the lovers’ meetings in this novella happen in the kitchen, where they share meaningful smiles and double entendres. When she refuses to give him tea, he draws her close to him and whispers in her ear, “I have seen myself in your eyes and I wish to see this face there all my life” (80). The construction of the romantic chronotope in kitchen literature is completed when the hero enters the heroine’s space –the kitchen – and declares his love. In its formation, the romantic chronotope in kitchen literature therefore resembles Bakhtin’s “meeting chronotope” of Greek adventure-time in so far as it unifies the spatiotemporal markers without merging them.

“Let Me Live” opens with Awaiz standing on the kitchen doorstep, watching Samaviya intently. This creates a “scene,” in Roland Barthes’ terms, which represents a domestic [End Page 7] romantic ideal to the readers. Barthes writes, “the first thing we love is a scene,” because “love at first sight requires the very sign of its suddenness” (192, emphasis in original). The readers sitting in their kitchens can relate to the scene, register the cucumber, the sweat, and the smoldering gaze of the lover, and recognize the significance of their love. The kitchen setting authenticates the romance by rooting it in the immediate reality of the readers. To quote Barthes, “the scene consecrates the object I am going to love” (192, emphasis in original). The kitchen literature love scenes are usually crafted with plenty of details: the color and style of heroine’s dress, her hair, the quivering cup of tea in her hands, and the blush on her cheeks.

My analysis of romantic chronotopes in kitchen literature also draws upon the dialogical readings of Lynne Pearce. Writing about Jeanette Winterson’s Sexing the Cherry (1989) and Toni Morrison’s Beloved (1987), she maintains that even though Bakhtin’s representation of chronotope is “blindly gender neutral,” her reading of these two texts reveals that “ all time and space is gendered; that every chronotope, like every house, city or nation is characterized by the sex of its ruling class” and we cannot escape the influence of gender (Reading Dialogics 175). In a later work, on contemporary feminist fiction, she further propounds that “what the heroines most desire are the spaces/places of romance rather than the man who presently ‘owns’ them” (“Another Time, Another Place” 109). According to Pearce, falling in love provides the lovers with a “metaphorical bridge” through which they explore the possibilities of another world, without losing sight of their old world (“Another Time, Another Place” 106-109). In the context of the present study, Pearce’s theorization helps to highlight the gendered space of the kitchen. Kitchen literature frequently asserts that a woman is the queen of the household and the kitchen is particularly her territory, space where the heroine goes for reflection and private deliberation on her love life. Therefore, when the macho, masculine figure of the hero enters the feminine space, the sociocultural space of the kitchen becomes the “charged and responsive” place in the romantic chronotope (Bakhtin 84). In this chronotope, time is celebrated in relation to the moment of love that is a verse, a simple declaration of “I love you” or a double entendre. Lisa Fletcher deliberates that “I love you” is the key to the plotting of romance in general as it draws a connection between the past and present and “encapsulates heterosexuality’s (impossible) claim to universality, timelessness and truth” (14, emphasis in original). The performative force of the speech act of love simultaneously depends on the knowledge that it has been said many times before and the demand of its conventionality. Hence, the speech act of love “invokes a kind of continuous present” (Fletcher 14-16). In most kitchen literature love stories, the speech act of love provides the temporal framework of the chronotope by an amalgamation of the past and present of the lovers, within the charged and responsive space of the kitchen. Chronotopicity in these romance narratives is arguably more dependent on the performativity of the poetic love utterance than contemporary Western romances because it provides figurative references to the physical union of lovers, which is otherwise absent from the text because of the socio-cultural limitation.

Adun, the hero of Sadaf Omar’s “Craving For A Look of Yours,” uses double entendre throughout the novella, which rattles the innocent heroine, Beila. Their first meeting takes place in the kitchen, where he startles her with his abrupt entrance and she bumps her head on a shelf, crashing many pots and amusing him with her clumsiness. As the plot and their love progress, the intensity of their kitchen rendezvous increases:[End Page 8]

Beila was looking absently at him. He looked so careless in a blue t-shirt and white trousers. The ends of his trousers were folded and stray rings of his light brown curled hair were adorning his forehead. His broad shoulders were indicators of the fact that he could fight the world for his love. Her reverie was broken when the maid put their breakfast on the table. She had taken one piece of her paratha[3] before Adun snatched her plate.

“ Sorry. I couldn’t resist the fragrance,” he said.

He tried to put a bite in her mouth but she pushed his hand away.

“I would have eaten poison from your hands, with relish,” he said mischievously, drew her closer abruptly and put her hand, which was still holding the piece of paratha, in his mouth. She sprang up from her chair as if electrocuted.

“You…you….are too much…” she stuttered.

“I know what I am. For you” (Omar 78).

Barthes states that the scene is not always visual, and it can have a “linguistic” frame: “I can fall in love with a sentence spoken to me” (193, emphasis in original). Adun and Awaiz’s utterances of love, charged with romantic overtones, act as a proxy for scenes of explicit sexual intimacy and place the narrative within cultural norms.

The corpus reveals a variety of bildungsroman in which the heroine learns to synthesize love with her desire for home and hearth or career choice or some contradictory cultural demand. In “Only You Are In My Heart,” the heroine Urwa is frightened by the idea of matrimony and resists the advances of the hero, Rawal. She learns to believe in love through her various encounters with other married and unmarried female relatives and acquaintances and accepts Rawal at the end. Khan’s story starts with Urwa coming out of the kitchen with a cup of tea for Rawal, who first tries to touch her hand while taking the cup and then moves “perilously” close to her, so much so that she can smell his perfume, which increases her heartbeats and her breath seems to stop. When Urwa’s apprehensions and fears have been resolved and the wedding date is fixed, Rawal yearns to meet his bride-to-be, which is a daunting task in a house full of guests, and a friendly cousin arranges his secret rendezvous with Urwa in the kitchen where she is making tea. Her response to Rawal’s “brimming with love” and “intoxicating” utterances of love is to blush furiously and lower her eyelashes (Khan). Movement of the spatiotemporal markers in the romantic chronotope comes full circle when the meeting between the lovers takes place in the kitchen, anticipating the journey of the couple to, presumably, another happy kitchen.

The highest level of bodily contact between the lovers in kitchen literature is holding hands or whispering in the ear. In the course of most romance narratives, the hero enters the feminine space where the utterance of love is usually accompanied by the highest degree of physical proximity between the lovers within the text. The kitchen in the hero’s home is the embodiment of a happily ever after future and a space where the heroine will rule after [End Page 9] her marriage. There are innumerable references to this happily ever after in kitchen literature. One example of it is the love letter that the hero Sarmad writes for the heroine Shabana, who is his next-door neighbour in Abida Ahmed’s novella “Make Me Beautiful.” His mother is ill and he seeks help from his neighbour. When Shabana opens the door, her hands are smeared with flour as she was making bread dough in the kitchen. He falls in love at first sight. Unaware of his sentiments, she helps his mother in the kitchen, cooks delicious food for them and leaves. Later he throws a rolled up love letter at her when she is drying her laundry on the rooftop, which reads:

How are you, Shab? I will not apologize for my frankness in naming you thus. You captured my heart without my permission so I have the right to call you with whatever name I want. The rice and fruit trifle you made yesterday featured in my dreams all night. I hope to bring you to my kitchen very soon as you have already entered my heart (183).

The utterance of love in this story is performed outside the space of the kitchen. However, the explicit references to the kitchen as a site of romance and happily ever after marks it as a love story of kitchen literature.

The meeting chronotope in most of kitchen literature love stories fulfils two of Bakhtin’s “architectonic function(s)” (98), and serve s as both opening and closure in the course of the text. In Aimal Raza’s “Season of Confessions,” the heroine Zubia is antagonistic towards the hero Hassan because of the misdeeds of his mother towards her mother, who were step-sisters. The events of the story consist of Zubia’s attempts to avenge her mother by refusing to offer dinner or breakfast to Hassan and his siblings, who visit to renew the relationship between their respective mothers. A pattern similar to previously quoted examples emerges when the agency of the hero moves into the private space of the heroine, invading her thoughts, winning her love and giving the readers (reading in the kitchen) a glimpse of the happily ever after in another kitchen, which will be her space in the hero’s home:

She was afraid to look into Hassan’s eyes. She had finished cooking and was cleaning the stove. He came closer and sat down near her. Zubia had impressed him a lot. She wasn’t rolling in luxury but she had a contentment, a softness about her which touched something deep in him.

“You are amazing Zubia. I will miss you in America. Will you miss me?”

She did not reply. Did not even look up. She hated him when he came and now that he was leaving, it seemed her breath was leaving her body.

“Will you miss me?” he asked again.

“Everyone who comes has to leave anyway,” she mumbled, barely hearing her own voice. Hassan came closer and held her hand. She wasn’t wearing gloves [End Page 10] this time. He hid her hands in his; swallowing them and looked straight into her eyes.

“Don’t you dare make the mistake of forgetting me” (Raza 98).

In this example, the hero’s utterance of “Will you miss me?” is charged with contextual significances and can be construed as an equivalent of “I love you” because of the proxemics involved. His utterance, connected with a gradual decrease of the physical distance between the lovers, charges the setting of the kitchen with multiple metaphoric meanings and becomes, in Bakhtin’s words, a “verbal stratagem” (98). This proximally and contextually charged utterance is a verbal device that is pivotal to the temporal framework of the story, connecting Hassan’s and Zubia’s past, present and future together. In most cases, the heroine’s transportation within the narrative, from one kitchen to another, is only a part of the happily ever after schema provided to the readers. However, in stories like Iffat Sehar Tahir’s “The Unsaid Prayer,” the meeting chronotope appears at the end when Abeeha, the heroine, is shown standing in the kitchen in the hero’s house, which is the space she is going to “rule” like the hero’s heart. While Abeeha is making soup for her mother-in-law, “with quick, lithe movements of her henna-colored hand,” the hero comes in, “covers her hands with his” and whispers sweet nothings in her ear (Tahir 184-85). As discussed above, in the emotionally charged space of the kitchen, trivial everyday utterances, to borrow Bakhtin’s expression, “takes on flesh” (84), and inform the temporal structure of the chronotope.

Another distinctive characteristic of the romance narratives of kitchen literature is that they closely link the expression of love with the preparation and consumption of “tea.” Farzana Kharal’s novella “Love Like January” documents several social dilemmas within the upper-middle-class extended family of the heroine Mashal, whose father’s infidelity resulted in her mother’s death and his second marriage, which led to his estrangement from her. Mashal makes tea five times in the story and on another occasion she prepares joshanda, a throat elixir. Like the heroines of other stories discussed above, she frequently comes in to or out of the kitchen – but in her case, there is no sense of ownership as she is living in her relatives’ house. The romantic chronotope is developed at the time when the hero Ashab takes small sips of the tea that she has prepared for him and feels envious of his aunt who is holding his lover’s hand. In this chronotope, the space of the kitchen is not described in the text as space and is only imagined as the happily ever after place in Ashab’s home. Ravissment is predominantly temporal in nature as it happens when Ashab fanaticizes physical proximity with Mashal while drinking tea and later through the poem that he recites in his imagination during family dinner:

O lover in the dense forest of your eyelashes

There is a season of fragmented glass

Just a glance

Utter destruction

[End Page 11]

The seasons in your eyes

Just scatter haunting vacuums in hearts

The people, the conversation, the food…everything vanished except her. He could not stop looking at her. He became restless. Why did he start looking into the depths of her eyes after ages? It should not have happened. There was a fire burning in those kohl-lined green eyes, which consumed him. Totally (Kharal 110-11).

Here, Ashab has to fantasize about his lover to a greater extent than the other romance heroes already discussed earlier, because Mashal does not have her own private space. In the absence of the kitchen as space, the chronotope has to be structured around the time of love, marked by the hero’s fantasies, his poetic utterances and kitchen as the happily-ever-after, imagined future place. The intricacies of romantic chronotopes in kitchen literature connect with the schema of the readers, who understand the formula of love that is presented through the cultural values observed by the protagonists and the domestic settings in these love stories.

To conclude, the romantic chronotope in the love stories of kitchen literature uses the space of the kitchen on both the diegetic and extra-diegetic levels. The familiarity of the domestic space transports the readers to the world of love, without affecting the sense of their immediate location. This is not, of course, the only use that kitchen literature makes of the space of the kitchen. It serves as a setting for negotiations between criminals in thrillers like “Namal” (Ahmad), and as a stage to showcase heroine’s infidelity in front of the hero in “My Companion” (Ishtiaq)[4]. Likewise, the preparation and presentation of tea in the kitchen is a favored trope by the authors, which can be put to a variety of uses. There are heroines who blush when the hero touches their hand while taking a cup of tea. There are also villains who manipulate the private space to victimize young women when they prepare tea. In short, this article has introduced the genre world of kitchen literature, which is ripe for further exploration with reference to additional uses of the “kitchen” as chronotope and the publication, distribution and author selection processes of the popular digests more generally.

[1] Urdu is the lingua franca of Pakistan.

[2] All quotations from the Urdu stories are my translations.

[3] A flat bread made from wheat and oil.

[4] Both novels were first published as serials in Shuaa and Khawateen digests. Popular digest serials are printed in book format immediately after the publication of their last episode. Here, I refer to the book format. [End Page 12]

Bibliography

Aftab, Rehana. “Let Me Live.” Kiran, vol. 40, no. 53, November 2017, pp. 58-98.

Ahmed, Abida Aabi. “Make Me Beautiful.” Shuaa, vol. 31, no. 52, June 2017, pp. 164-90.

Ahmed, Nimra. Namal. IlmoIrfan Publishers, 2014.

Ali, Kamran Asdar. “‘Pulp Fictions’: Reading Pakistani Domesticity.” Social Text, vol. 22, no. 1, 2004, pp. 123-45.

Bakhtin, M. M. The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays. Translated by Michael Holquist, University of Texas Press, 1981.

Barthes, Roland. A Lover’s Discourse : Fragments. 1st American ed., Hill and Wang, 1978. Art Main PC 2440. B3613 1978.

Bernstein, Susan D. “Ape Anxiety: Sensation Fiction, Evolution, and the Genre Question.” Journal of Victorian Culture, vol. 6, no. 2, Jan. 2001, pp. 250-71. Taylor and Francis+NEJM, doi:10.3366/jvc.2001.6.2.250.

Caldas-Coulthard, Carmen Rosa. “‘Women Who Pay For Sex. And Enjoy It:’ Transgression Versus Morality In Women’s Magazines.” Texts and Practices: Readings in Critical Discourse Analysis, Taylor & Francis, 1996, pp 250- 270.

Cosslett, Tess. “Feminism, Matrilinealism, and the ‘House of Women’ in Contemporary Women’s Fiction.” Journal of Gender Studies, vol. 5, no. 1, Mar. 1996, pp. 7-17, doi:10.1080/09589236.1996.9960625.

Dornan, Reade. “Kitchen Sink Drama.” Western Drama Through the Ages: A Student Reference Guide, edited by Kimball King, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2007, pp. 451-453.

Editorial Board. “Journey of Bright Moments.” Shuaa, no. 52, August 2018, pp. 17-25.

Fletcher, Lisa. Historical Romance Fiction: Heterosexuality and Performativity. Ashgate Publishing Company, 2008.

Fletcher, Lisa, Beth Driscoll and Kim Wilkins. “Genre Worlds and Popular Fiction: The Case of Twenty-First-Century Australian Romance.” The Journal of Popular Culture, vol. 51, no. 4, Aug. 2018, pp. 997-1015. Crossref, doi:10.1111/jpcu.12706.

Flora, Cornelia Butler. “The Passive Female: Her Comparative Image by Class and Culture in Women’s Magazine Fiction.” Journal of Marriage and the Family, vol. 33, no. 3, Aug. 1971, p. 435. CrossRef, doi:10.2307/349843.—.

Friedan, Betty. The Feminine Mystique. 1983 ed., W.W. Norton & Company, 1963.

Hermes, Joke. Reading Women’s Magazines: An Analysis of Everyday Media Use. Wiley, 1995.

Hughes, Winifred. The Maniac in the Cellar: Sensation Novels of the 1860s. Princeton University Press, 2014.

Ishtiaq, Farhat. My Companion. Ilm-o-Irfan Publishers, 2008.

Khan, Ayesha. “Only You Are In My Heart.” Shuaa, no. 52, January 2006, p. 85-111.

Kharal, Farzana. “Love Like January.” Shuaa, no. 53, February 2018, pp. 94-145.

King, Andrew. “‘Literature of the Kitchen’: Cheap Serial Fiction of the 1840s and 1850s.” A Companion to Sensation Fiction, edited by Pamela K. Gilbert, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2011, pp. 38-53. Crossref, doi:10.1002/9781444342239.ch3.

Omar, Sadaf. “Craving for A Look From You.” Kiran, vol. 41, no. 52, C May 2018, pp. 62-91.

Pearce, Lynne. “Another Time, Another Place: The Chronotope of Romantic Love in Contemporary Feminist Fiction.” Fatal Attractions: Re-Scripting Romance in Contemporary Literature and Film, edited by Lynne Pearce and Gina Wisker, Pluto Press, 1988, pp. 98-111.

[End Page 13]

—. Reading dialogics. Hodder Arnold, 1994.

Rae, William Fraser. “Sensation Novelists: Miss Brandon.” North British Review, vol. 43, no. 04, September, 1865, pp. 180-204.

Raza, Aimal. “Season of Confession (Of Love).” Khawateen Digest, no.53, March 2018, pp. 91-120.

Siddiqui, Nadia. “Who Reads Urdu Women’s Magazines and Why? An Investigation of the Content, Purpose, Production and Readership of Urdu Women’s Digests.” International Journal of Media and Cultural Politics., vol. 8, no. 2-3, 2012, pp. 323-34.

—. “Women’s Magazines in Asian and Middle Eastern Countries.” South Asian Popular Culture, vol. 12, no. 1, Jan. 2014, pp. 29-40. CrossRef, doi:10.1080/14746689.2014.879423.

Steere, Elizabeth. The Female Servant and Sensation Fiction: Kitchen Literature. Palgrave Macmillan US, 2013.

Tahir, Iffat Sehar. “The Unsaid Prayer.” Khawateen Digest, no. 53, November 2015, p. 184-85.

Winship, Janice. Inside Women’s Magazines. Pandora Press, 1987.

Zubair, Shirin. “‘Not Easily Put-Downable’: Magazine Representations and Muslim Women’s Identities in Southern Punjab, Pakistan.” Feminist Formations, vol. 22, no. 3, 2010, pp. 176-95. CrossRef, doi:10.1353/ff.2010.0024.

—. “Qualitative Methods in Reseaching Women’s Literacy: A Case Study.” Women, Literacy and Development; Alternative Perspectives, edited by Anna Robinson-Pant, Routledge, Taylor and Francis, 2004, pp. 85–99.

[End Page 14]