Romance fiction explores culturally-specific notions of intimacy. Because it portrays a group’s conventions about love and amorousness, it can provide outsiders glimpses of norms and practices. Authors can describe and critique features of a given social context—such as racism or religious prejudice—in ways that inform outsiders and, at the same time, [End Page 1] allow insiders to recognize and identify with behaviors and situations described. For example, Conseula Francis’ analysis of Addicted by Zane demonstrates how romance narratives provide Black women “a powerful counternarrative” to the “oversexed vixens of rap videos or gonzo porn” (173). Romance as a venue to foil extant stereotypes about Black women’s sexuality also situates Black female protagonists as receivers of the eros love typically reserved for White female characters and allows for nuanced social commentary related to the Black American experience. In her analysis of Brenda Jackson’s Tonight and Forever, Julie E. Moody-Freeman outlines how safe sex love scenes between Black protagonists reflect the promotion of Black women’s sexual health during the “age of HIV/AIDS” when the author published the novel (112). Francis and Moody-Freeman’s explorations of African American romance narratives offer powerful critical tools in observing cultural elements of a social group and ways in which the genre may be used by authors to address biases, stereotypes, and social issues affecting its members at the most intimate levels.

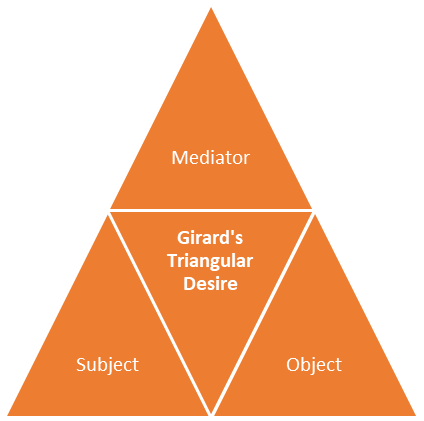

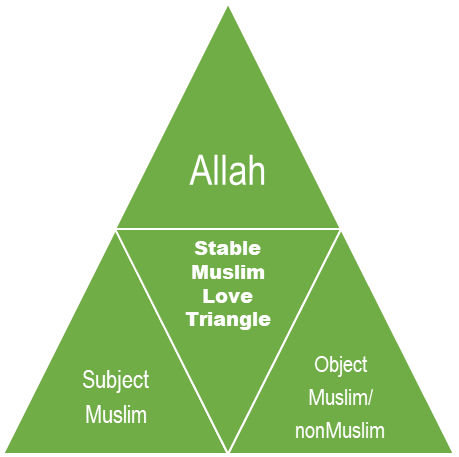

African American (AA) Muslim romance fiction is sui generis. It combines Islamic, African American, and American notions of love, courtship, and sexual dialogue. In this article, I explore four romances—Areebah’s Dilemma: Love or Deen by Karimah Grayson, American Boy by Zara J., Khadijah’s Life in Motion by Jatasha Sharif and His Other Wife by Umm Zakiyyah—and argue that they have a consistent, and uniquely AA Muslim, structure. Applying René Girard’s theory of triangular desire to the Islamic thematic underpinnings of AA Muslim romance, I show the consistent presence of a Stable Muslim Love Triangle (SMLT), a culturally-specific triangular romance structure permeating romantic plots. Girard grants fluidity to love triangles in Deceit, Desire, and the Novel: Self and Other in Literary Structure and presents one love triangle containing a mediator of desire that dictates the yearning of the subject for the object of desire (2). AA Muslim romance novels consistently include a SMLT triangular structure of desire, wherein Allah (swt)[i] firmly maintains position as mediator of desire at the love triangle’s apex. Consequently, when determining whether to pursue or maintain a romantic relationship with the object of desire, the subject unfailingly relinquishes individual passions and acquiesces to the protocols set by Allah (swt) through interpreted Islamic teachings.

There are three primary manifestations for the SMLT in the surveyed AA texts:

- Muslim subject – Muslim object.

- Muslim female subject – non-Muslim male object.

- Muslim male subject – non-Muslim female object.

Each of the above manifestations of the SMLT involves nuances of religious application and identity that jeopardizes the joining of the novel’s protagonists. When both are Muslim, one protagonist’s un-Islamic behavior imperils the couple’s relationship. When one of the protagonists is non-Muslim, the lack of belief disrupts the SMLT.

AA Muslim romance is a distinctive subgenre reflecting unique notions about love and romance held by African Americans resulting from the infusion of Islamic observations with American heritages. The analyzed works illustrate the multiple cultural identities which comprise the multi-layered American Muslim experience. [End Page 2]

Cultural Identity

Layered Islamic and African American identities encapsulated in the AA Muslim experience simultaneously feed its members’ cultural productions. Therefore, it is necessary to distinguish notions of culture and identity that create a distinctive AA Muslim cultural identity.

Although the terms “identity” and “culture” are usually used interchangeably, following Stuart Hall’s approach allows one to explore the differences among the various nationalities, ethnicities, and identities that comprise American Muslim culture while recognizing a common Islamic culture.[1] Hall asserts that identity serves as a point of human delineation: “Identities are constructed through, not outside, difference” (4). Therefore, one establishes identity by creating a distinction from another. An individual may have layered identities from which they have the ability to draw and clarify differences from those around them, although Hall’s identity binary allows for specified application of terms “culture” and “identity”.

Categorizing identity as a space of distinction makes room to apply an explicit definition to the term “culture.” Hall, as well as Geoffrey H. Hartman, designate culture as a sphere of appreciated similarity. Hall asserts that culture comprises practices, representations, languages and customs (439), while Hartman notes that culture is a “specific form of embodiment or solidarity” (36). In other words, a culture comprises associations with people sharing languages, customs and heritages, holding the same values, and relating to representations of shared experiences.

Thus, the term “cultural identity” indicates a distinction within shared experiences. In American Secularism, Joseph Baker and Buster Smith explain that where culture provides artifacts with which an individual may make a stable connection with others, identity is that with which we emotionally describe and differentiate ourselves (504). Personal identification is subjective and varies based on societal influences and internal processes (Baker and Smith 504). Individual relationships to cultural artifacts and desires to identify with cultural nuances of a social group vary as well. AA Muslims, and the authors who identify as such, assert identities distinct from the broader American Muslim culture, wherein they share similar Islamic cultural practices, customs, language[2], and representations. As a result, cultural artifacts from the AA Muslim cultural identity highlight a unique American Muslim cultural experience, influenced by social intersections of religion, race, gender, and national origin. The SMLT expounded upon in this article outlines a standard trope in AA Muslim romance reflective of American religious romances (i.e. Evangelical, Puritanical, etc.), demonstrating literary connections between novels written by authors of varying religions who weave faith with human love.

African American Muslim Cultural Identity

Dominant culture tends to assume Muslims are immigrants or descendants of immigrants from the Middle East or South Asia (MESA). Like many other social spheres in the United States, AA and Black Muslims encounter erasure of their identities resulting from intersections of race and religion via the promotion of a “foreign” MESA Muslim archetype. [End Page 3] Consequently, publishers, agents, etc. feed into the creation of an “ideal type” of American Muslim, and reinforce it, restricting ventures of the inclusion of Muslims to members of those two finite demographics. AA Muslim authors experience professional erasure which limits markets for and appreciation of their literary work. Since having an opportunity to highlight their distinctive—and distinctively American—identities matters to them, they must self-publish and create small presses.

I coined the term Native-born American (NbA)[3] Muslims to highlight social groups whose members have an extended American heritage and merge intersections of the country’s social intersections[4] with Islam. I elaborated on some distinctions existing in the culture when I created the NbA Muslims online platform:

The dynamics of the native-born American Muslims [NbA Muslims] hybrid culture are complex. There are a variety of socio-cultural topics that warrant in-depth academic investigation. For example, many NbA Muslims belong to multi-religious families. Consequently, there are various familial situations such as family reactions to conversion as well as interacting with the family while maintaining an Islamic ethic. Additionally, there are social concerns such as interfaith communal dialogue, gender relations and roles, community involvement, racism, contact with the immigrant Muslim population, and artistic expression (NbA Muslims).

The NbA Muslim cultural identity hybridizes Islamic and American conventions to produce unique social groups which implement components from each. The NbA African American[5] Muslim cultural identity includes the social intersection of race, influenced by the country’s historical and modern racial systems. Thus, literary productions of NbA AA Muslims reflect how the group redefines social intersections of race, gender, and nation for themselves.

The adoption of the Islamic faith by native-born Americans generates an additional cultural divergence in the American Muslim subculture. Unlike immigrant Muslim populations, the Islamic experiences of native-born African-Americans[6] primarily consist of conversion and adoption of Islam as a new faith.[7] Converts comprise ninety-one percent of native-born American Muslims (Pew Research). Therefore, Islam is new for the majority of native-born American Muslims, who must construct interpretations and observances for their new religion.

AA Muslims also maintain ownership of their Americanness, stemming from heritages extending from ancestral enslavement, recognized citizenship after emancipation, and continual assertion of their socio-political capital. They resist the reductive national narrative that Muslims are perpetually foreign.

NbA AA Muslims also encounter racism and anti-Blackness within Muslim spheres, which augment systemic racism from the broader society. Examining experiences of racism and racial micro-aggressions perpetrated by White and non-Black[8] Muslims reveals social clashes among adherents in the United States. The predominance of said racism means that many AA Muslims encounter a paradox, wherein the egalitarian ideals contained in their religion are superseded by the racial objectification inflicted on them (Karim 37). [End Page 4]

NbA African American Muslim Romance

African American Muslim authors represent the largest subset of writers in the NbA Muslim hybrid culture.[9] My research uncovered over thirty Muslim fiction[10] titles written by AA Muslims. A consequence of the continued lack of diversity the publishing industry, the majority of authors self-publish or become indie publishers.[11] Most AA Muslim authors are not full-time novelists. Consequently, publishing remains inconsistent, with no stable annual book releases[12] save a few professional authors like Umm Zakiyyah, Sa’id Saleem, and Umm Juwayriyah.

Of these thirty texts, I chose six to critically examine.[13] Some tropes shared by these works across genres diverged from those used by American Muslim authors who are not African American.[14]

- Many titles include conversion experiences and interactions between main characters and non-Muslim characters with whom they share familial (i.e. parent, sibling, relative, etc.) ties, as well as intimate friendships and/or relationships.[15]

- Plots tend to center the Islamic faith, and many characters are motivated by or recognize the significance with their relationship to Allah (swt).

- There is a connection to the tradition of AA novelists seeking to utilize fiction to articulate their cultural experiences, raise social consciousness, and affect social change—known as the Black Literary Tradition.[16]

Through an extensive African American heritage, AA Muslim authors tap into a rich literary tradition spanning centuries with some steady messaging, and infuse it with culturally-specific Islamic observances and interpretations reflective of members merging faith and race. Also, when centering the Islamic faith and characters’ fictional relationships with Allah (swt), AA Muslim romance authors often produce recurrent themes in Muslim fiction novels that highlight a triangular desire similar to those contained in Christian romance, but with a few marked differences, which will be noted later.

Faith-based Romance

Romantic distinctions stemming from religious and belief structures offer a subtle but significant divergent perspective differing from secular norms exclusively centering the heroine and hero. In romance fiction, the central (and occasionally the only) focus of the plot is on the love relationship and courtship process of the two main characters (Ramsdell 4; Regis 14). Characters and elements exterior to the couple serve to facilitate or foil the developing relationship, resulting in their lifetime joining either through marriage or committed partnership.[17] However, romance critics Lynn S. Neal and Valerie Weaver-Zercher present romance formulas wherein God maintains omnipotent influence over protagonists in Christian love stories. Neal explains in Romancing God: Evangelical Women and Inspirational Fiction how belief or lack of belief plays a pivotal role in the protagonists’ ability to unite in Evangelical romance (Neal 6): “Evangelical romances place one’s relationship with God before all other relationships [and the characters are] transformed [End Page 5] and brought together through the power of God’s love” (5). In Thrill of the Chaste: The Allure of Amish Romance Novels, Weaver-Zercher posits a comparable objective for Amish fiction: to encourage readers to cherish and prioritize the sacred love of God (127). Both Neal and Weaver-Zercher seem to agree that “God is the ultimate lover who pursues them and will always be there for them” (Neal 159). However, numerous approaches to faith, love and romance makes it necessary to appreciate nuances beyond one construct. Since multifaceted representations of God as the ultimate lover across Christian denominations requires distinct analyses, so too should literary criticisms of works from authors of different faiths.

Similar to Christian romance models, romances written by AA Muslim authors prioritize Allah (swt) in the development of the romantic plot, barrier to the protagonists’ union, and ultimate objective in the love story. Although not an “ultimate lover” pursuing the protagonists—something I will unpack further later—the deity remains at the pinnacle of the Stable Muslim Love Triangle prevalent in AA romance fiction, whereby at least one of the protagonists’ commitment to Allah (swt), as opposed to attraction to the object of desire, serves as a lynchpin to the union.

The Love Triangle

The love triangle is a frequent feature of romance novels. In The Look of Love: The Art of the Romance Novel, Jennifer McKnight-Trontz outlines ways in which married protagonists encounter challenges to their happily ever after (HEA) via “the heartache of matrimonial trouble by way of adulterous affairs, love triangles, and divorce” (35). However, romance love triangles are not limited to causing disruption in a marriage. David Shumway states that modern “popular novels or stories are much less likely to make love triangles explicitly adulterous [but] the love triangle remains fundamental to popular fiction of the turn of the century” (45). Love triangles are one manifestation of the “triadic structure”[18] of relationships, wherein one subject is excluded (Shumway 14-15). Love triangles present an opportunity to provide “the barrier” to the protagonists’ union, an essential romance element.

Pamela Regis describes the barrier in romance fiction as a series of scattered scenes containing external (outside the protagonists’ minds) or internal (inside of at least one of the protagonists’ minds) conflicts that establish reasons for the inability for the lovers to unite (32). In a romance containing at least one love triangle, an individual often serves as an external barrier to the lovers. However, a common theme in religious romance involves a protagonist’s internal conflict between a commitment to God and human love for another character, generating a love triangle jeopardizing both relationships. René Girard’s theory of triangular desire serves as a base to reveal how AA Muslim romance authors consistently place Allah (swt) at the apex of romantic structures, maintaining principle authority in determining the viability of love between characters.

René Girard’s Triangular Desire

The love triangle involving Allah (swt) as the ultimate arbiter of the feasibility of a union between the protagonists is a constant in African American romance. African [End Page 6] American authors often include an internal barrier where one or more characters use(s) Islamic parameters to decide whether to initiate or continue a romantic relationship. In Areebah’s Dilemma, the titular character Areebah chose not to pursue a relationship with her love interest, non-Muslim Frankie. Although Areebah was in love with Frankie, the character decided, “no matter how much she cared about him, she loved Allah [swt] the most” (134-135). Areebah’s decision indicates the level of dedication to her faith as well as Allah’s (swt) role as the “mediator of desire” (Girard 2) in a love triangle comprising the novel’s protagonists and God. Girard describes the “mediator of desire” as the “model” with which the “subject” pursues objects of desire (2). Girard uses the triangle as a “spatial metaphor” that expresses the triple relationship, wherein, “The mediator is there…radiating toward both the subject and the object” (Girard 2). The mediator of desire dominates all of the connections in the love triangle, and the subject forsakes personal desires and aspirations for the mediator’s criteria.

A subject surrendering desire to a mediator is present in various forms of literature. Girard uses Don Quixote as an example of the “subject/disciple” surrendering to a mediator (in this case, Amadis and chivalry), allowing it to supersede his desires (2). Others have extended Girard’s mediator of desire love triangle for specific cultural applications. Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick states, “The triangle is useful as a figure by which the ‘commonsense’ of our intellectual tradition schematizes erotic relations, and because it allows us to condense in a juxtaposition with that folk-perception several somewhat different streams of recent thought” (597). Sedgwick utilizes Girard’s literary love triangle as a vehicle to convey homosocial bonds between the subject and the mediator (598), demonstrating the pliability of Girard’s model.

Lisa M. Gordis outlines two Christian triangular love structures, both of which maintain a rivalry between a supernatural God and human lovers. In Puritan texts, the human lover—typically the husband—becomes a rival with God for the affection of the love interest—usually the wife. In these works, God is a “full partner” and “active presence” as in most Christian romances, but He presents a superior lover to the wife in particular and an adversary to the husband’s affections (Gordis 324). Portrayals include God as “jealous” supreme being in the love triangle who punishes spouses for having too much love for their [End Page 7] corporeal love interest (325). The structure is triadic, with God vying predominantly with the husband for the affection of the wife, demanding priority in her heart through punishment and death.[19]

Evangelical romances reinforce the superiority of divine over human love, but through less grave content. Gordis asserts that the demand to uphold the genre’s happily-ever-after convention results in God being, “less a jealous God than a matchmaking deity, sending his beloved children earthly comfort” (331). Consequently, the humans must “learn to balance their triangulated relationship,” and God, while consistently victorious, continues to compete with the lovers for amorous supremacy (333).

AA Muslim romances differ from both of these Christian models in their placement of Allah (swt) in the love triangle. The distinctions among and between Christian and Muslim triangular models of desire[20] deserve sustained critical attention beyond the scope of this article. I will focus here on one significant difference regarding the position of Allah (swt) in the Muslim love triangle as well as His roles as competitor, intermediary, and arbitrator for the human couple and stabilizer of the triangular desire when the relationship dynamics between the lovers change.

Instead of positioning Allah (swt) as a victorious competitor—either through pain/death or enlightenment—for love between human subjects, AA Muslim romance authors continually recognize the immediate superior status of the deity in the love triangle. One or both human subjects pursue His affection and approval to the point of deferring to His protocols when determining the suitability of the object of desire. Amina Wadud posits that any relationships between any two people or two groups and Allah (swt) are essentially one of horizontal reciprocity, explaining, “Each of the two persons are sustained on the horizontal axis because the highest moral point is always occupied metaphysically by Allah [swt]” (850). Wadud’s horizontal placement of humans at the base of the triangle structure not only stabilizes Allah (swt) at the pinnacle, it infers and reinforces Islamic teachings regarding the deity’s independence as well as His appreciation for love between humans without the need to compete with it.[21]

AA Muslim fiction presents an additional departure from the Christian romance rivalry between God and the couple worshiping him, in that authors regularly emphasize the individual relationships each character maintains with the deity. Aysha A. Hidayatullah expands on Wadud’s horizontal reciprocity and explains that humans simultaneously occupy “horizontally equivalent” spaces under Allah (swt) while each also maintaining separate “vertical” relations to Allah (swt) (168), which they ideally prioritize. Habeeb Akande includes individual characteristics, stressing worship and love of Allah (swt) as premier attributes in a love interest. Akande highlights “taqwa” (god-consciousness) for men and “righteousness” for women as desirable qualities in potential partners (205, 240).[22] Writers of American Boy, Khadijah’s Life in Motion, Areebah’s Dilemma, and His Other Wife include pressures on love triangles stemming from characters’ embodiment of or challenges with belief or exhibiting righteous behaviors. Main characters must consequently navigate barriers to attaining a happily-ever-after because love interests either do not satisfy expectations of “righteousness” or do, but are not the immediate characters to whom the main characters are attached. The primacy of the vertical relationships existing between Allah (swt) and human subjects highlighted in AA Muslim romance situates Allah (swt) as the exalted arbitrator in the horizontal relationships between them. Furthermore, the authoritative role of Allah (swt) remains stable, whether plots include the deity as a [End Page 8] matchmaker like in some Evangelical texts, wherein he sends “his beloved children earthly comfort rather than deferring their happiness to the heavenly plain” (Gordis 331), or a barrier resulting from issues of faith or lack thereof in the object of desire.

In Muslim romances, Allah (swt) is the mediator of desire, and the Muslim protagonists submit to His dictates and protocols to determine whether to pursue the “object.” The level of commitment each Muslim subject has to Allah (swt) as mediator of desire varies, and Girard posits that simpler characters do not utilize a mediator (2).[23] However, Allah’s (swt) mediator status remains and generates a Stable Muslim Love Triangle at the foundations of AA Muslim Romance, even with the presence of subsidiary love triangles.

Numerous AA romance novels contain standard love triangles involving three characters. In American Boy by Zara J, main character Celine struggles to keep the father of her child Umar with her and away from her rival Tara. In Khadijah’s Life in Motion by Jatasha Sharif, Tyrone returns from prison to find out that his live-in lover Pamela converted to Islam and had a beau in the form of Muslim police officer Ibrahim. Deanna conspires to keep her husband Jacob and best friend Aliyyah apart in His Other Wife by Umm Zakiyyah. However, in addition to the external barriers presented by love triangles between characters, AA romance habitually contain internal barriers emanating from a SMLT, where Allah (swt) is the mediator of desire at the apex. The AA romance novels Areebah’s Dilemma: Love or Deen, American Boy, Khadijah’s Life in Motion, and His Other Wife reveal how Islamic ideals emphasizing love of Allah (swt) produce a SMLT comprising of the deity, heroine, and hero, the specifics of which vary depending on religious identity and adherence.

In a small research study I conducted, all of the self-identified AA Muslim novelists indicated that they intentionally wrote to 1) convey NbA Muslim experience, 2) as a means of da’wah and social commentary. Authors also informed the survey that they included Muslim characters as literary vehicles to highlight Islamic faith practices according to their interpretations (Abdullah-Poulos). In many instances, authors construct Stable Muslim Love Triangles, where faith serves as an internal barrier against as well as a catalyst for the union of romantic protagonists. Consequently, Allah (swt) influences the Muslim’s affection and the moral compass with which the believer determines how to interact with people, including a potential or current love interest. These authors consistently highlight marriage as the primary objective of romantic interactions in their works, and position Allah (swt) as establisher of the protocol with which the believer determines who is suitable. The parameters for an acceptable spouse set in the Quran include: 1) faith,[24] 2) marital status,[25] and 3) familial ties.[26] Observant Muslims should follow the dictates of the religion to assess the qualifications of a potential spouse.[27] Muhammad al-Jibaly describes marriage as “a bond held together by mutual rights and responsibilities,” and spouses should have certain characteristics that make them competent in what is ideally a fair partnership (1) according to divine dictates. Al-Jibaly uses revelation and prophetic guidance to focus on obligations between the spouses, extending the deity’s authority in the horizontal relationships between the spouses as well as horizontal ones directly with him.[28] Thus, Allah’s (swt) exalted status and dual prevailing influence stabilizes the triangle of desire. [End Page 9]

The Stable Muslim Love Triangle (SMLT)

African American romance authors often use the Stable Muslim Love Triangle to serve both as a barrier to and the catalyst for the protagonists’ ultimate union. Two static components of the SMLT are the heteronormative nature of the triangle and marriage. Beyond these fixed confines, the composition of the SMLT, as well as its presentation as a barrier or catalyst, shifts due to a number of factors. Two prominent factors affecting the status of a SMLT in AA romance are 1) observation of the faith, and 2) the religious identity of the object. The former of these two factors influences the SMLT concerning two Muslim characters, while the latter applies to love triangles involving a Muslim subject and non-Muslim object. AA romances containing one or both of these factors generate three distinctive love models, as noted above:

- Muslim subject and object;

- Muslim woman and non-Muslim man;

- Muslim man and non-Muslim woman.

Exploring each of these love models reveals the SMLT’s role in fostering and impeding connections between protagonists.[29]

Muslim Subject and Object

Novels include romance triangles with two Muslim protagonists. However, characters’ daily religious application and characteristics frequently differ. Consequently, African American romance contains unions with two Muslim characters strengthened by the Stable Muslim Love Triangle, as well as those weakened resulting from a shift in the mediation of desire dictated by Allah/the mediator. One protagonist in romance upholds an idealized Muslim archetype of a practicing Muslim who prays, fasts, and prioritizes their relationship with Allah (swt) in their daily interactions and interpersonal connections. In His [End Page 10] Other Wife, protagonists Jacob and Aliyyah both fulfill the idealized Muslim archetype. The novel contains scenes of hero Jacob performing Qiyaam al-Layl, a special late-night prayer to seek guidance from Allah (swt) about his marriage to Deanna and love for Aliyyah (182). Similarly, many of the scenes in His Other Wife show Aliyyah offering Qiyaam al-Layl as well as Fajr (early morning) prayer and reading Quran (46, 63-64, 111-112). The praying of Qiyaam al-Layl and Fajr denote a level of devotional excellence in Muslim culture, and Zakiyyah frames the protagonists as idealized Muslim archetypes. Satisfying the idealized Muslim archetype solidifies the viability of the Jacob and Aliyyah’s union and reinforces a positive SMLT between them. However, Jacob pursues Aliyyah while married to Deanna, whose behavior diminishes her ability to exhibit an idealized Muslim archetype and, we will later see, eventually jeopardizes the couple’s marriage.

Unlike the characters engendering Muslim devotional traits, an insufficient exhibition of religious excellence or an error made in the story line disqualifies a flawed Muslim character from obtaining idealized status. There are numerous major character defects contained in the examined novels that may make a character ineligible for idealized Muslim status. Umar in American Boy is a devoted Muslim but flawed by engaging in illicit sex through a one-night stand with his non-Muslim co-worker Celine. Tyrone’s sexual violence via his attempted rape of Pamela/Khadijah in Khadijah’s Life in Motion similarly disqualifies him as an idealized Muslim archetype despite his regular offering of prayers and attending Islamic classes at the masjid. Umar’s brother Khalid in American Boy drinks and gambles; Ahmed in Her Justice is extremely violent. These character flaws prevent them from being ideal Muslims. Whether a character is an idealized or flawed Muslim, their relationships follow a common pattern: if both partners in a relationship apply religion to their lives, their relationship solidifies; if one of them fails to do so, it fractures. Ultimately, characters who observe the Islamic faith to any significant degree defer to Allah’s mediation of desire, which delineates faith as the primary characteristic for a spouse in a Muslim marriage.

In the studied texts, novelists largely prioritize faith and piety at the pinnacle of desirable characteristics for a Muslim subject in AA romance, and when a Muslim object falls short of satisfying the expectations of the subject, there is a breakdown in the relationship. Observant Muslims tend to place religious dedication as their top preference when searching for a spouse. In His Other Wife, Jacob’s relationship with his first wife Deanna begins to deteriorate as his distaste for her perceived un-Islamic behavior increases. In one scene, Jacob and Deanna are driving home and she slaps him (63-64), which introduces readers to her abuse and violation of Islamic protocol regarding slapping (Muslim 6321). Jacob initially tolerates Deanna’s “slaps, hits, punches, or kicks” (63-64) as a part of their marriage, but when layered with more perceivably un-Islamic behavior, such as lying, harassment, and appearing on television with “her hijab pushed back displaying half her hair” and “her lips in a pout, shiny with red lipstick” (184-185), Jacob ultimately dissolves the marriage. Leaving Deanna is not easy for Jacob; she had a firm grasp on him through marriage and sexual control. In one scene, Deanna approaches Jacob during their separation and offers herself for sex. Jacob, torn by his emotions, “yearned for Deanna in a maddening way, and he hated himself for it” (132). Jacob eventually sees Deanna’s proposition for “halal intimacy” as “physical and psychological manipulation” (132). Jacob prays to Allah (swt), “O Allah, give me strength,” spurs Deanna’s advances, and walks away. Jacob’s distaste for his wife’s un-Islamic behavior supersedes the hero’s desires, and Jacob appeals to Allah/Mediator to intercede. Despite being Muslim, Deanna is unable to secure idealized Muslim archetype [End Page 11] status. The combination of Deanna’s physical abuse, immodesty, and aggressive sexual behavior transforms the SMLT she shares with Jacob from a catalyst of their union into a barrier, and ultimately, they divorce.[30]

In AA romance, the Muslim subject concedes to Allah/Mediator and the mediation of desire to initiate and maintain an amorous relationship. The Muslim subject will seek and dispose of a Muslim object love interest based upon the former’s conforming of resistance to the mediation of desire via adherence to the Islamic faith. As demonstrated in His Other Wife, the object’s failure to comply with the subject’s mediation of desire jeopardizes the SMLT.[31] The surveyed stories also convey a theme among AA romance authors that once the SMLT destabilizes, the subject rejects the flawed character, and there are no apparent means of redemption for the object. I have not yet found a novel with a plot structure diverging from this model.

Muslim Woman and Non-Muslim Man

African American Muslim romances with a Muslim subject and non-Muslim object play out differently depending on participants’ gender. Islamic law differentiates between potentially permissible relationships between a Muslim man and a non-Muslim woman and always forbidden relationships between a Muslim woman and a non-Muslim man. As a result, Muslim women choosing to marry non-Muslim men often meet cultural and religious resistance. AA Muslim romance authors address the gender distinction when Muslim characters explore relationships with non-Muslims, and the Stable Muslim Love Triangle functions as catalyst (when the relationship is permissible) or barrier (when it is forbidden).

Unlike the more common romance trope between a Muslim man and a woman outside of the faith, AA romance authors infrequently pair a Muslim woman with a non-Muslim man. One clear example, Areebah’s Dilemma, demonstrates the effects on the SMLT of a Muslim woman desiring a non-Muslim man and their potential union. Realizing that a romantic relationship with Muslim Areebah was impossible, non-Muslim Frankie begins to explore Islam as a faith option. In Areebah’s Dilemma, Frankie accepts Islam, develops his spiritual connection with Allah (swt), and marries Areebah. However, before Frankie’s conversion, Areebah is perplexed and wavers back and forth between avoiding and pursuing him.

Areebah is clearly smitten with Frankie. She loses sleep thinking about him and even considers being his second wife (137).[32] She takes the opportunity to arrange an “accidental” meeting with Frankie at the hospital when he visits his dying mother. Grayson writes, “When she saw Frankie…exit the elevator, she almost jumped into his arms” (112). However, Areebah is aware that Frankie is married and eventually meets his wife, Felicia. Consequently, Areebah and Frankie face an external barrier presented as Frankie’s marriage to Felicia, as well as an internal barrier that manifests because Allah (swt) is Areebah’s mediator of desire, and Frankie’s non-Muslim status challenges their union.

Felicia dies in the novel, removing the couple’s external barrier. Areebah and Frankie engage in a series of text and Facebook direct messages, reigniting their love for each other. However, the SMLT remains an obstacle, and hero and heroine remain distant. Consequently, instead of acting on her carnal desire for Frankie, Areebah appeals to her mediator, Allah (swt), to make Frankie interested in conversion and make him a suitable beau. Because of Allah’s (swt) supremacy over Areebah’s desire, Frankie becomes an object “emptied of its [End Page 12] concrete value and enclosed in an aura of metaphysical virtue” (Dee 391). In other words, Areebah wants an idealized Frankie that simultaneously embodies her temporal desires and the necessary spiritual markers by becoming a possession of the Mediator/Allah (swt). Once Frankie converts, Areebah experiences a fusion of her desire for Frankie and the need for her as a Muslim to adhere to the mediation of desire constructed by the Mediator/Allah (swt) in Islamic marital protocols.

Allah (swt) also becomes Frankie’s mediator of desire when he converts. Wanting to ensure that his conversion would be authentic and not because of his feelings for Areebah, Frankie distances himself from Areebah and begins to study Islam. Frankie did not want to “enter into a way of life for anyone except himself” (168). The character was “determined to learn more about Islam” regardless of whether or not he ultimately ended up with Areebah (168). Frankie’s fervor to study Islam reflects a common theme in AA romance and culture, where non-Muslims develop an interest in the religion because of a Muslim love interest. The shift that takes place in Frankie reflects the malleability of the SMLT, which is constant but not stagnant. Girard mentions that love triangles may change in shape and size without destroying the “identity of the figure” (2). Therefore, the Allah/mediator, Areebah/Muslim Subject, Frankie/non-Muslim object triangle transitions into an Allah/mediator, Areebah/Muslim Subject, Frankie/Muslim object triangle, which reflects Girard’s assertion that the stability of the love triangle emanates from the mediator and subject, while the object “changes with each adventure” (2). The changeable nature of the object – in this case, Frankie – promotes diversity in the SMLT without dissolving the structure.

The relationship between Areebah and Frankie shows a significant pitfall that a Muslim woman encounters when the object of her affection is a non-Muslim male. In practice, Muslims globally do not always observe limitations on Muslim women’s marriage to non-Muslim men. There are instances of Muslim women entering interfaith marriages (Abbas), and there are examples of Muslim imams who perform such ceremonies. However, they face considerable pushback from those strictly adhering to the faith’s traditional restriction. Riad Fataar, a senior leader of South Africa’s Muslim Judicial Council, asserts, “Everybody knows that such a marriage is not permissible in Islam. It is ridiculous to think otherwise” (Moftah). Therefore, Grayson’s portrayal reflects a circumstance resulting from a Muslim woman’s fundamental observation of Islamic law, which frequently occurs in orthodox Muslim cultures.

The lack of a valid marriage between Muslim women and non-Muslim men simplifies the SMLT between such characters in AA romance. However, when the lovers are a Muslim male and non-Muslim female, the triangle’s nature increases in complexity. AA authors offer prolific storylines comprised of variable relationships between Muslim heroes and non-Muslim women.

Muslim Man and non-Muslim Woman

Compared to Muslim women, the Islamic faith affords more latitude to Muslim men regarding amorous relationships. Although non-physical courtship and heteronormative marital sex apply to Muslim men, the religious status of the inamorata is not as stringent. Islamic law, based on interpretation of a Qur’anic verse (Al-Quran, 5:5), traditionally allows Muslim men to marry certain non-Muslim women, specifically Jews and Christians. Similar to a relationship between a Muslim female protagonist exhibiting interest in a non-Muslim [End Page 13] man, African American authors predominantly respect the Islamic parameters interpreted by the culture for amorous plots involving a male adherent and woman who falls outside of these allowed groups. The majority of the novels include self-identified Christian women and Muslim men.

Muslim male characters in AA romance typically do not desire to sacrifice the idealized Muslim archetype to preserve their relationships with non-Muslim women. In some novels, Muslim male characters attempt to coerce their non-Muslim lovers—with whom they frequently have an existing or past sexual relationship— to convert, insisting that failure to do so will jeopardize the union. In American Boy, Umar refuses to marry Christian heroine Celine, whom he has impregnated, unless she converts. Umar is determined to have a Muslim family; he explains to Celine, “Growing up, my mother always talked about having a good Muslim wife and marrying the ideal woman. It was embedded in us” (180). Umar’s desire for a Muslim wife dually satisfies his desire as well as his obedience to his perception of what Allah/the Mediator arbitrates for him, which further impresses the urgency of the provision of Celine’s conversion before their nuptials. Umar’s ultimatum threatens more than their relationship. Celine’s pregnancy means that if she and Umar remain unmarried when she gives birth, their child will be born illegitimate.

Legitimacy among American Muslims is extremely important; illegitimate children are subject to numerous legal issues. For example, if Umar’s child is born out of wedlock, Islamic law dictates that he or she will have Celine’s last name and the child will not be able to inherit from Umar. Both Umar and his family may be unaware of Islamic law. However, the author presents them as a traditional Muslim family observing Islamic protocols, so it is doubtful. Umar and his family prioritize the main character having a wife who satisfies the idealized Muslim archetype over the interests of the unborn child. The fact that Umar’s “ideal” Muslim wife is available in the form of Tara makes it easier for him to court her and overlook how his decision to marry her instead of Celine will affect his baby. For Umar, standards about a Muslim wife from his upbringing supersede the reality of the need for him to marry a woman, who is an acceptable candidate for marriage under Islamic law, to protect the legitimacy of his child, which is arguably the priority. Consequently, the novel contains two love triangles. The Allah/mediator à Umar/subject à Celine/object presents a barrier love triangle and the Allah/mediator à Umar/subject à Tara/object a catalyst love triangle.

Ultimately, Umar commits to the SMLT with Tara at the detriment of his child, which was acceptable for the novel’s Muslim characters. Umar abandons Celine and their baby because of her non-Muslim status and marries Tara. However, by the novel’s end, Umar eventually takes his newborn child from Celine to raise with his new bride. He leaves the mother of his child alone and showing obvious signs of post-partum depression. The love triangle between Umar, Celine, and Tara excludes Celine, not because of anything she does but because she is a nonbeliever in the Islamic faith. Like Frankie in Areebah’s Dilemma, the main character flaw is being non-Muslim and aggravating the SMLT in each romance plot via their unsuitability according to Allah (swt) as the mediator of desire.

AA romance characters exemplify many issues that exist in AA culture. The romantic connections depicted in their love models involve either 1) two Muslims or 2a) a Muslim woman desiring a non-Muslim man or 2b) a Muslim man seeking to develop or maintain a relationship with a non-Muslim woman. These represent multifaceted applications of the SMLT, which firmly places Allah (swt) at the pinnacle governing the decisions a Muslim character makes about an object of desire. [End Page 14]

The SMLT is a consistent trope in AA romance. It is comprised of Allah (swt) as the mediator in a mediation of desire and one Muslim subject acquiescing to his dictates when determining whether to pursue or maintain a relationship with an object of desire. Variations of the SMLT appear along the lines of religious identity. In novels containing plots with a Muslim subject desiring a Muslim object, a character’s lack of piety and the inability for the object to satisfy the idealized Muslim archetype expectations destabilize the SMLT and disrupt the relationship. When the subject is a Muslim woman, and the object is a non-Muslim man, Islamic marital prohibitions, established by the mediator Allah, disqualify the union. Muslim men may marry Christian and Jewish women in addition to Muslim women. Consequently, when the object of desire for a Muslim male subject is a non-Muslim woman who self-identifies as either, conversion to transform the object and satisfy the idealized Muslim archetype creates the primary barrier to the union. The SMLT demonstrates culturally-specific usage of triangular structural relationships prevalent in romance literature by AA romance authors.

AA Muslim romances demonstrate the existence of a distinctive AA Muslim hybrid culture, resisting stereotypes of American Muslim culture as inherently foreign. Moreover, they offer sharers of the depicted experiences—AA Muslims—opportunities to negotiate tensions stemming from simultaneously belonging to AA, American, and Muslim American communities as well as the global Ummah.[33] Authors also provide unique romantic structures indicative of their cultural experiences, generating SMLT tropes that place Allah (swt) at the pinnacle as an authority over and not a competitor to the viability of protagonists’ love connections.

[i] (swt) is an abbreviation for the English transliteration Subhana wa Ta’ala, meaning “Glory be to Him, the Highest.” It is customary among Islamic scholarship to include the phrase after writing Allah’s name in their works.

[1] It is important to note that the term “Islamic culture” encompasses an array of practices, customs, and representations, with ideally Quranic and prophetic underpinnings – the interpretations of which vary individually, ethnically, regionally, etc.

[2] While American Muslims speak a multitude of languages, including English, Arabic maintains a widespread influence because of the use of the language in religious practices.

[3] Native-born American in the scope of this study comprises African-Americans, Euro-Americans, and Latino-Americans. The premise here is that these three Muslim groups represent specific American experiences and heritages with significant historical influence in the development of the country’s socio-political dynamic.

[4] i.e. socio-political, racial, gendered, nationalistic, etc.

[5] The term “Black” is often interchangeably used by people who also self-identify as “African American”. However, the term “African American” more specifically indicates a cultural identity and heritage connected to the enslavement of Africans in the Americas, to which not all Americans of African descent identify.

[6] Conversion populations also include NbA Latinx, Euro-American, and Native American Muslims.

[7] It is important to note that while there is a large conversion population in the NbA African American Muslim cultural identity, the subculture also contains extensive generational Muslim families, with some having as many as five generations. [End Page 15]

[8] Non-Black in this context represents a cross-section of identities within Muslim communities, including Middle Eastern, South Asian, Asian, and Latinx. In addition, African American Muslims may encounter bias from African-immigrant Muslims, who often seek to disassociate from them—the complexities of which are beyond the scope of this article.

[9] Although there are works of fiction written by NbA Muslims identifying with other ethnicities (i.e. Euro-American, Latino-American, etc.), I did not find a sufficient number of novels to present a well-rounded representative sample of those hybrid subcultures.

[10] Muslim fiction is a budding genre in the United States, with authors from numerous backgrounds comprising American Muslim culture, and Muslim authors and publishers still need to solidify a stable definition. However, there is a current consensus that Muslim fiction is 1) authored by self-identified Muslim authors and 2) contains Muslim characters. I have pushed back on those reductive parameters in conversations with authors and publishers because they tend to alienate certain Muslim author-produced texts.

[11] A few examples of indie publishing presses launched by AA Muslim authors include Mindworks Publishing and University Publications.

[12] The last observable AA Muslim romance, Her Justice, was published in 2016.

[13] Ironically, I informed at least two authors (Umm Zakiyyah and Nasheed Jaxson) that their texts could be considered romances. The author categorized them outside of the genre. Umm Zakiyyah’s text His Other Wife remains so, but Nasheed Jaxson’s text Her Justice is now categorized with romance titles.

[14] Presently, most American Muslim fiction authors write mainly YA and children’s books. I discovered few romance titles by Muslims centering Muslim love interests and the faith—AA Muslim romance authors being the primary exception. There are Muslim authors like Sa’id Saleem writing general romance, but most titles do not fit within current parameters of Muslim fiction, which raises questions about them that makes further exploration by scholars, authors, and the industry necessary.

[15] Intimate relationships serve as a barrier catalyst in some AA Muslim romances, which will be explored later.

[16] Novels written by African Americans often serve as more than sources of entertainment. These literary works frequently reflect historical and social conditions of the African American experience as well as serve as “weapons for social change” within the culture (Carby 95). I explored this aspect of AA Muslim authorship in my thesis and think delving deeper into how authors tap into this tradition is important to understanding complex cultural connections contained in the subculture.

[17] The emergence of diverse romance plots that include polyamorous relationships push against the boundaries of heteronormative monogamous tropes, which makes them worthy for deeper exploration beyond the scope of this article.

[18] According to Shumway, triadic structures in narratives are not exclusively comprised of love interests and may include “father/daughter, king/court” as well as other examples. Triadic structure relationships are “intersubjective because all three subjects of the narrative are represented as both desiring and desirable” (15; emphasis in original).

[19] In her analyses of The Autobiography and The Parable of the Ten Virgins by Thomas Shepard as well as A Christale Glasse for Christian Women by Phillip Stubbes, Gordis provides examples of Puritan female characters who endure suffering and end up on their death beds resulting from an imbalance of their male love interest’s (husband’s) love for her or his inability to handle the stronger pull of God on his bride (325-330). [End Page 16]

[20] American Muslims are hardly monolithic or stagnant in their interpretations and implementation of the faith. The AA Muslim authors and works examined highlight a cultural sampling of a specific experience, which contain additional facets not revealed through textual analysis, which encourages further examinations and expansion.

[21] Quran and hadith both contain references to Allah’s (swt) supremacy and self-sufficiency without needing or desiring worship or love from His creation. In the Quran, Allah (swt) says, “O mankind, you are those in need of Allah [swt], while Allah [swt] is the Free of need, the Praiseworthy” (35:15). Therefore, unlike the Puritan and Evangelical texts, God is not a competitor for or jealous of love or affection between humans, nor does he punish humans for loving each other too much in an Islamic context.

[22] Although, Akande quotes specific ahadith (sayings of the Prophet Muhammad (saws) as well as scholarship in a way that categorizes them as gender-specific, Quranic teachings encourage adherents of both genders strive to attain taqwa and righteousness. Human subjects in AA Muslim triangular romance will ideally seek said qualities in the love interest.

[23] In Areebah’s Dilemma: Love or Deen, Areebah’s son Baqir has a non-Muslim girlfriend. However, as a minor character, the absence of Allah as mediator of desire is not relevant to the novel’s plot.

[24] Abdul A’La Madudi explains that the prohibition against marrying a “mushrik” (Al-Baqarah, 2:221) secures a believer from being influenced by a non-believing spouse and corrupting the faith in the home (volume 1, 162). He asserts, “One who sincerely believers in Islam can never take such a risk merely for the sake of the gratification of his lust” (volume 1, 162). Madudi’s default use of “his” indicates how androcentric Quranic exegesis from men can be, which influences the broader culture and reinforce misconceptions that Muslim women do not have inclinations towards non-Muslim men—mushrik or otherwise. Except for Karimah Grayson, the majority of Muslim novelists surveyed reinforced this generalization. Grayson’s Areebah’s Dilemma features a Muslim woman torn between her faith and the non-Muslim man she loves, something not uncommon in African American Muslim culture despite efforts to ignore it.

[25] Madudi also expounds on the allowance for Muslim men to marry chaste women from the “People of the Book”—generally accepted to mean Christian and Jews (Al-Maidah, 5:5). He mentions that the sanction contains a caveat requiring the women be “chaste” (volume 3, 20), something insufficiently addressed in AA Muslim romances. While there is yet to be a plot with a Jewish love interest, the chastity of Christian ones is not addressed, and is, in fact, often clearly nonexistent, which will be examined later. Muslim male protagonists in Khadijah’s Life in Motion and American Boy contain love triangles with apparent sexual history between the subject and object of desire.

[26] Prohibitions against certain women one may marry are mostly self-explanatory lists and infer the male gender by default: “Also (prohibited are) women already married…” (An-Nisaa, 4:22-24). Madudi does clarify that maternal and sibling marital injunctions extend to step- and foster parents and siblings (volume 2, 110). AA Muslim authors have yet to include any type of risqué plots involving incestuous desire.

[27] Additional sources that codify acceptable spouses for Muslims exist. There are ahadith (sayings of the Prophet Muhammad) that provide further description for Muslims deciding upon a candidate for marriage, but the mentioned Quranic passages serve as the foundation. [End Page 17]

[28] For example, al-Jibaly asserts, “A woman’s obedience to her husband is an obedience to Allah (swt) in the first place, because he ordered it (73). al-Jibaly’s obtuse treatment of the term “obedience” disturbingly reinforces spiritually-coercive gender oppression by inferring that male domination over women is by divine mandate, but his argument does exemplify the simultaneous vertical and horizontal sovereignty Allah (swt) retains as well as negates notions that the deity is jealous; rather, He directs interactions between the spouses.

[29] NB: I’ve concluded that the repetitive use of the terms “Muslim man,” “Muslim woman,” Non-Muslim man,” and “non-Muslim woman” necessary to highlight the defined heteronormative parameters to which the surveyed authors adhere as well as leave an “open door” for extension of the present frame to include love models that may not neatly fit into the current one. For example, I do not want to erase the possibility that there may be, now or in the future, an AA Muslim author who includes LGBTQ love interests, which would require new analyses.

[30] Deanna also experiences a mental breakdown and hospitalization as further punishment for her un-Islamic behaviors. Although the author reveals that she is a child sexual assault survivor, Deanna suffers a series of humiliations that justify Jacob’s leaving her and marrying Aliyyah, making her the other woman despite being married to the hero.

[31] The Muslim subject and Muslim object are gender-neutral terms. There is an opportunity for portrayals a woman who defers to Allah (swt) as mediator of desire and a man who jeopardizes the SMLT through un-Islamic behavior. Interestingly, I did not discover an example of an African American romance author writing this dynamic in a plot.

[32] Polygyny is never a viable option in the novel. Frankie remains an ineligible suitor for Areebah until after his wife Felicia dies and he converts. Interestingly, the majority of African American Muslim authors surveyed “toy” around with notions of polygyny in their works, and never present it as a functional marital option despite its practice in many AA Muslim communities. Examining portrayals of polygyny is beyond the scope of this article, but it does warrant further exploration.

[33] Ummah is a broadly-used term in Muslim cultures to denote the larger Muslim fellowship. [End Page 18]

Works Cited

Abbas, Rudabah. “‘Halal’ Interfaith Unions Rise Among UK Women – Al Jazeera English.” Al Jazeera: Live News | Bold Perspectives | Exclusive Films, 31 Dec. 2012, https://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/features/2012/12/2012122795639455824.html. Accessed 13 Mar. 2016.

Abdullah-Poulos, Layla. “Muslim Love American Style: Islamic-American Hybrid Culture and Native-Born American Black Muslim Romance.” MA thesis, SUNY Empire State College, 2016. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses. Accessed 6 Aug. 2018.

Akande, Habeeb. A Taste of Honey: Sexuality and Erotology in Islam. Rabaah Publishers Ltd., 2015.

Al Quran. Interpretation of the Meanings of the Noble Qur’an in English Language: A Summarized Version of Al-Qurtubi, and Ibn Kathir with Comments from Sahih-Al-Bukhari. Translated by Muhammad T.D. Al-Hilali and Muhammad M. Khan, Maktaba Dar-Us_Salam Publications, 1986.

Al-Jibaly, Muḥammad. The Fragile Vessels: Rights and Obligations between the Spouses in Islam. al-Kitaab & as-Sunnah Publishing, 2000.

Baker, Joseph O, and Buster G. Smith. American Secularism: Cultural Contours of Nonreligious Belief Systems. New York University Press, 2015.

Bukhari. The Translation of the Meanings of Summarized Ṣaḥîh Al-Bukhâri: Arabic-english = Ṣaḥīḥ Al-Bukhārī. Translated by Khan M. Muhammad, Maktaba Darul Salam, 1994.

Carby, Hazel V. Reconstructing Womanhood: The Emergence of the Afro-American Woman Novelist. Oxford UP, 1987.

Dee, Phyllis S. “Female Sexuality and Triangular Desire in ‘Vanity Fair’ and ‘The Mill on the Floss’.” Papers on Language and Literature, vol. 35, no. 4, 1999, p. 391-416, Academic OneFile, http://link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/A58163348/AONE?u=esc&sid=AONE&xid=cd5b42b2. Accessed 24 Sept. 2018.

Francis, Conseula. “Flipping the Script: Romancing Zane’s Urban Erotica.” Romance Fiction and American Culture: Love As the Practice of Freedom?, edited by William A Gleason and Eric M. Selinger, Ashgate, 2016, pp. 167-180.

Girard, René. Deceit, Desire, and the Novel: Self and Other in Literary Structure. Johns Hopkins Press, 1965.

Gordis, Lisa M. “Jesus Loves Your Girl More Than You Do: Marriage as Triangle in Evangelical Romance and Puritan Narratives.” Romance Fiction and American Culture: Love As the Practice of Freedom?, edited by William A Gleason and Eric M. Selinger, Ashgate, 2017, pp. 323-346.

Grayson, Karimah. Areebah’s Dilemma. Create Space, 2015.

Hall, Stuart, and Gay P. Du. Questions of Cultural Identity. Sage, 1996.

Hartman, Geoffrey H. The Fateful Question of Culture. Columbia UP, 1997.

Hidayatullah, Aysha A. Feminist Edges of the Qur’an. Oxford UP, 2014.

Jaxson, Nasheed. Her Justice. Kindle edition, Nasheed Jaxson, 2014.

J, Zara. American Boy. University Publications, 2014.

Karim, Jamillah A. American Muslim Women: Negotiating Race, Class, and Gender within the Ummah. New York UP, 2009.

Maududi, Abdul A’La. The Meaning of the Qur’ān. 3 vols. Translated by ‘Abdul ‘Aziz Kamal, Islamic Publications, 1988.

[End Page 19]

McKnight-Trontz, Jennifer. The Look of Love: The Art of the Romance Novel. Princeton Architectural Press, 2002.

Moftah, Lora. “South Africa Mosque Holds First Interfaith Marriage: Muslim Woman, Christian Man Marry in Controversial Ceremony.” International Business Times, 23 Mar. 2015, https://www.ibtimes.com/south-africa-mosque-holds-first-interfaith-marriage-muslim-woman-christian-man-marry-1855788. Accessed 13 Mar. 2016.

Moody-Freeman, Julie E. “Scripting Black Love in the 1990s: Pleasure, Respectability, and Responsibility in an Era of HIV/AIDS.” Romance Fiction and American Culture: Love As the Practice of Freedom?, edited by William A Gleason and Eric M. Selinger, Ashgate, 2016, pp. 110-127.

Muslim, Ibn -H.-Q, and Abdul H. Siddiqui. Ṣaḥiḥ Muslim: Being Traditions of the Sayings and Doings of the Prophet Muhammad As Narrated by His Companions and Compiled Under the Title Al-Jāmiʻ-Uṣ-Ṣaḥīḥ. Sh. Muhammad Ashraf, 1971.

NbA Muslims. “Purpose.” NbA Muslims, Patheos, http://www.patheos.com/blogs/nbamuslims/purpose/. Accessed 5 Sep. 2016.

Neal, Lynn S. Romancing God: Evangelical Women and Inspirational Fiction. U of North Carolina P, 2006.

Pew Research. “Converts to Islam.” Pew Research Center, Pew Charitable Trusts, July 2007, http://www.pewresearch.org/daily-number/converts-to-islam/. Accessed 6 July 2015.

Ramsdell, Kristin. Romance Fiction: A Guide to the Genre. Libraries Unlimited, 2012.

Regis, Pamela. A Natural History of the Romance Novel. Kindle edition, U of Pennsylvania P, 2003.

Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky. “Between Men.” The Novel: An Anthology of Criticism and Theory, 1900-2000, edited by Dorothy J Hale, Blackwell, 2006, pp. 586-604.

Sharif, Jatasha. Khadijah’s Life in Motion. Jatasha Sharif, 2012.

Shumway, David R. Modern Love: Romance, Intimacy, and the Marriage Crisis. New York UP, 2003.

Wadud, Amina. Inside the Gender Jihad: Women’s Reform in Islam. Kindle edition, Oneworld Publications, 2013.

Weaver-Zercher, Valerie. Thrill of the Chaste: The Allure of Amish Romance Novels. Johns Hopkins UP, 2013.

Zakiyyah, Umm. His Other Wife. Kindle edition, Al-Walaa Publications, 2016.

[End Page 20]