What is love according to Leonard Cohen?

“It is in love that we are made; / In love we disappear,” Leonard Cohen sings after having been abandoned by the “Crown of Light, O Darkened One” with whom he experienced a momentary union (“Boogie Street”). Love is seen as a force which chooses the singer to serve it (“Love Calls You by Your Name”); it is a scorching power in which he extinguishes [End Page 1] his existence (“Dance Me to the End of Love”); a purely divine phenomenon which unites both masculine and feminine forces inside him (“Joan of Arc”) and gives meaning to his earthly existence (“There Ain’t No Cure for Love”). “Love Itself” is seen as the light coming “through the window, / straight from the sun above,” a kind of transforming power that opens the door towards the Divine (“Love Itself”).

In an almost liturgical language, as we shall see, Cohen describes the receiving of love through prayer, repentance, and bodily pleasures. Yet he is also afraid of love, as he sings in a cover version of Frederick Knight’s “Be for Real,” “I don’t want to be hurt by love again.” Moreover, Cohen presents himself as a slave to both Divine and Human love, a man who continuously fails in his faithfulness to each. His work propounds that the profane does not exclude the sacred in the language of love and that the human body, and lust for it, may anticipate the attainment of Divine love (“Light as the Breeze”).

Divine Love and Mysticism

In the song “Love Calls You by Your Name,” the singer implies that love arrives when one is between two unspecified states: “But here, right here, / between the birthmark and the stain, / between the ocean and your open vein, / between the snowman and the rain, / once again, once again, / love calls you by your name.” According to him, love is a force that is revealed neither when one is alive or dead. It is somewhere between, in the liminal space, on the margins of daily life. One receives it in loneliness when “you stumble into this movie house, / then you climb, you climb into the frame.” It appears when we are able to leave the human existence behind, or when we are capable to forget our self and let the soul escape into some “other frame.” Then love comes and calls us by our “name,” which means not only that it recognizes us, but also that it recognizes us as worthy of love.

Here one may ask, but where is the other person to give and accept love? Cohen does not portray love in such a way. To Cohen, love is not limited to the relationship between two partners. Indeed, in the very same song, he sings that he has to leave the woman for some other kind of love: “I leave the lady meditating on the very love which I, I do not wish to claim.” He even describes the “bandage,” the symbol of healing, loosening and calls: “Where are you, Judy, where are you, Anne?” which sounds as if he was trying to address the women who had hurt him and who can no longer hold him back from his thirst for the spiritual form of love. (This is one of the reasons for ending the relationship with Marianne Ihlen, described in the song “So Long, Marianne”).[1] However, the song “Love Calls You by Your Name” suggests that the physical love prepares the singer for the attainment of the Divine love. The chorus then reveals that this attainment is temporary and that the whole experience will repeat and thus prove its cyclical nature: “Once again, once again, / Love calls you by your name.”

Throughout Cohen’s work, the word “name” signifies earthly human existence. (It is distinct, therefore, from “The Name,” which is a traditional Jewish term for G-d.) As in many Biblical stories, from Abram / Abraham and Sarai / Sarah onward, a change of name in Cohen’s work thus implies a change of self, a new existence, and perhaps therefore a new relationship to love, both human and divine. In the song “Lover, Lover, Lover,” for example, Cohen presents a dialogue between himself and the Father G-d in a variety of religious and [End Page 2] mystical idioms, in this case with both Biblical and Islamic (Sufi) references, and much of their conversation concerns the singer’s history and future as one who loves and is loved.

The first verses of the song go: “I asked my father, / I said, ‘Father change my name.’” As the subsequent lyrics reveal, in order to have his “name” changed, the singer has to overcome his bodily desires and the “filth and cowardice and shame” that they have brought him. This is corroborated by the Father G-d responding to the singer: “I locked you in this body, / I meant it as a kind of trial” (“Lover, Lover, Lover”). Understanding this, we see that Cohen’s plea for the new name is, in reality, a plea for letting his soul escape and return to the Father G-d. Sufi teaching refers to this version of repentance as tawba, which entails regretting of the past sins and the return to G-d and to that which is inherently good (cf. Khalil). As Sylvie Simmons attests, Cohen studied the Sufi poet Rūmī (303), and the use of “lover” in this song’s chorus to name both G-d and the human singer, each of whom sings “lover, lover, lover, lover, lover, lover, lover come back to me” to the other, echoes Sufi thought. Although the Sufis in general distinguish between the lover and his Beloved―the lover is a human being, Beloved represents G-d— this dichotomy is to be overcome once the lover and the Beloved become one. The repetition of “lover” in this song invokes this overcoming of the dichotomy, and the rhythmic, incantatory quality of this refrain, when sung by Cohen, recalls the chanting of “La ilaha ilallah,”[2] one of the creeds of Islam, just as the ecstatic music of the song resembles the musical accompaniment for sama, the ritual ceremony during which the Sufis of the Mevlevi order perform their whirling dance. The dance results not only in the re-enactment the death of their ego and rebirth, but also in the attainment of Divine love and wisdom through the union with the Creator on the vertical axis spanning between the Earth and Heavens (cf. Friedlander). (On a more Judaic note, the seven-times repeated word “lover” may speak of the seven days in the creation of the world, with emphasis on love as a creative force characterising each day, and finally the seventh day celebrated as Sabbath.)

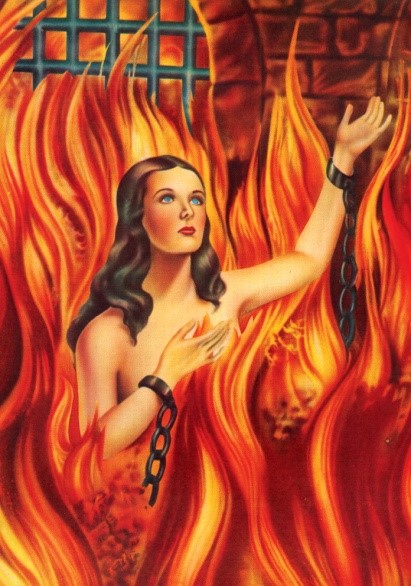

Such a union and the subsequent rebirth is also portrayed in another song, this time using Christian imagery: “Joan of Arc.” The song insinuates that the soul qualifies itself to accept divine love only after the trial period of unfulfilled longing and solitude. The soul is portrayed as a lonely “bride” represented by the character of Joan of Arc, while G-d is the bridegroom represented by the “flame” pursuing her.[3] In a poem from the collection The Energy of Slaves, Cohen acknowledges that he is “the ghost of Joan of Arc” (32), and hints at the possibility that the soul described is his own. In addition, on the back cover of his first album, Songs of Leonard Cohen, there is a picture of her engulfed in flames. Ira Nadel says that Cohen found this picture as a postcard in a Mexican magic store and felt that he was this woman looking for an escape from “the chains of materiality” (154-155). The Christian concept of anima sola, a soul burning in purgatory and waiting for salvation is quite apt for this description. Therefore, the song portrays a purifying annihilation in the arms of the Lord represented by the flame. [End Page 3]

Joan of Arc, the soul, is tired of the war; in other words, she is tired of living a solitary life seen as a kind of warfare against love and her body because she is a virgin. Now she is longing for “a wedding dress or something white / to wear upon [her] swollen appetite.” Her solitude and pride are to be abandoned before she will be consumed by love and born once again.

However, Cohen does not rely only on Biblical and Islamic symbolism in order to portray the soul’s purification process. In the song “Ballad of the Absent Mare,” we may see how Jewish symbolism collides with Cohen’s Zen practice and other mythical motifs. As Ira Nadel points out, the journey which the cowboy undertakes to find his mare follows to some extent an old Chinese text, “Ten-Ox Herding Pictures” (225-226), which illustrates ten stages of Zen practice.[4] In this song, then, the soul is not a woman longing for purification nor a man longing to return to his Lover / Father G-d, but rather a mare pursued by a cowboy: a spiritual seeker looking for an elusive, redeeming Beloved who is ultimately an aspect of himself.

As in the traditional Ox-herding narrative, the seeker in Cohen’s poem is an Everyman trying to attain enlightenment—a completion of self that is also, paradoxically, a loss of self—through taming the animal. For us, the most important of the series is the eighth picture in which the tamer and the bull both disappear in their union. Yet Cohen changes the narrative, both in its imagery and in its plot. First, he turns the image of a masculine bull into a mare: a shift that does as much to Westernize the parable—the soul is represented as feminine in most Western traditions—as his displacement of the story to an idyllic American setting. Having made these shifts, Cohen can retell the “Ten-Ox” story as though it were a love story. Unlike the first picture in the “Ten-Ox” series, in which the bull is wandering the plains and cannot be tamed, Cohen signals that the cowboy once kept the mare close to him and is about to depart to find her again.

As the song begins, the cowboy is injured, and his loss makes him solitary and repenting: a motif familiar from the songs I have discussed so far. Then, suddenly, the mare grows tamer, standing “there where the light and the darkness divide” (“Ballad of the Absent Mare”). This liminal space recalls those listed in “Love Calls You by Your Name,” but with this difference: where Cohen once again speaks about the threshold between the life and death, [End Page 4] he does so here by invoking Biblical imagery, specifically from the creation story in Genesis, as though we had returned to a moment outside of space and time. This biblical echo is reinforced by Cohen’s having the cowboy quote from the Book of Ruth to declare his love for the mare. “He leans on her neck / And he whispers low, / ‘Whither thou goest / I will go’” (KJV, Ruth 1:16). Unlike Ruth’s love for her mother-in-law Naomi, however—and very much in keeping with Buddhist teaching―the singer indicates that this union will be impermanent, which is one of his most consistent statements:

Now the clasp of this union

who fastens it tight?

Who snaps it asunder

the very next night

Some say the rider

Some say the mare (“Ballad of the Absent Mare”)

We do not know whether the union will be broken by the cowboy or the mare, but we know that, as the Zen series portrays, the rupture begins a new circle in which the cowboy will once again be alone, and the initiatory experience of the annihilation / rebirth of the soul will repeat.

In another song that fuses Biblical and Zen imagery, “Love Itself,” Cohen explores in close detail the experience of solitude as a necessary means to attain Divine union. After his return from the Zen Monastery in 2001 he commented that this song portrays a “rare experience of dissolution of self”:

I was sitting in a sunny room, watching the motes of dust, and accepted their graceful invitation to join in their activity and forget who I was, or remember who I was. It’s that rare experience of dissolution of self, not the careful examination of self that I usually work with. I played it for a couple of brother monks and sister nuns and they said it was better than sesshin—a seven-day session of intense meditation (rpt. in Burger 484).

In the lyrics, an entity Cohen calls “Love Itself” comes unexpectedly and is compared to light. “Rays of love” enter the singer’s “little room,” which implies, with regard to Cohen’s output, one’s heart. The light coming into this room makes little particles of dust visible and, in a moment of enlightenment, the singer sees them dancing in the air. Out of this dust, he sings, “the Nameless makes / A Name for one like me,” which implies that love resurrects him from “the dust”—recreates him as in the biblical story of Adam’s creation (cf. Genesis 2:7)—and thus gives meaning to his existence. In a more peaceful version of the scenes described in “Love Calls You by Your Name,” the singer becomes realised in such a love, so that love may call him by his “real” name. As in the “Ballad of the Absent Mare,” this recreating of love is an initiatory experience which lasts for a while and then disappears. “I’ll try to say a little more,” the song concludes: “Love went on and on / Until it reached an open door – / Then Love Itself / Love Itself was gone.”[5]

The album on which “Love Itself” appears, Ten New Songs (2001), returns to this Zen experience and the momentary union described above, often giving them a more Cabbalistic touch. In the first verses of the song, “Boogie Street,” for example, Cohen sings: “O Crown of [End Page 5] Light, O Darkened One, / I never thought we’d meet. / You kiss my lips, / and then it’s done: I’m back on Boogie Street.” In his commentary on the song, Eliot Wolfson assumes that the singer depicts a state after being unexpectedly struck by “the primordial light so bright that it glistens in the radiance of its darkness” (135). This certainly carries connotations of the revelation of light in Kabbalah, which springs out from its hiding place and is only to be seen thanks to its “concealing and clothing itself” (Cordovero, qtd. in Matt 91), just as Cohen’s names for the divine here—“Crown of Light, O Darkened One”―call to mind the highest Sefirah in the Kabbalistic system: Keter or Crown, the infinite, boundless or Ein Sof. Each verse of the song offers an initiatory and ephemeral experience of love taking place outside the ordinary world, and each returns the speaker to that ordinary world of “Boogie Street.”

One final instance will show the complexity of Cohen’s use of Jewish, Sufi, and Christian symbolism all at once. In the song “The Window,” Cohen speaks of a spiritual journey of the soul in three stages: solitude, suffering, and the final union in which she is annihilated. “Why do you stand by the window,” the song begins:

Abandoned to beauty and pride

The thorn of the night in your bosom

The spear of the age in your side

Lost in the rages of fragrance

Lost in the rags of remorse (“The Window”).

The soul depicted is in the state between two worlds: the primordial darkness of creation and the secular world. The window symbolises the threshold between the two worlds. The fact that the soul is described as having a thorn in her bosom and “the spear of the age in [her] side” gives the song a Christian cast, as this may echo Jesus’ Crown of Thorns and the spear of the Roman soldier piercing the side of Christ. Yet the soul is further described as “lost in the rages of fragrance,” which calls to mind the Havdalah Ceremony performed in the end of the Sabbath, during which observant Jews smell fragrant spices in remembrance of the departing Sabbath Spirit. In this imagery the soul would seem to be suffering from the loss of the Sabbath’s peace and the extra Sabbath soul called Neshamah yeteirah—although this perhaps also recalls Christ’s sense of being abandoned by the Divine when dying on the Cross (cf. Matthew 27:46 and Mark 15:34). In both cases, we can see the song as describing the return of the soul to the body as something painful and difficult.

The singer then pleads for Love the Saviour to come and gentle this suffering soul, but Love, too, is described in bewildering series of ways:

O chosen love, O frozen love

O tangle of matter and ghost.

O darling of angels, demons and saints

and the whole broken-hearted host—

Gentle this soul (“The Window”).

First, Love the Saviour is portrayed as “frozen love” which means that his love is constant and unchanging—but “frozen” also suggests something cold, or at least not yet flowing. He is also described as “a tangle of matter and ghost,” which could be transcribed as “a tangle of the flesh and soul,” which points to the fact that the singer is a human being harbouring [End Page 6] the Divine soul—but also suggests Christ (born of matter and the Holy Spirit or Holy Ghost). “The whole-broken hearted host” likewise stands for the “host” in the Eucharist, Christ, but also all of those who suffer, since G-d is said to be close to those who have a broken heart (Psalm 34:18).

The following stanza (which includes some of Cohen’s alternate lines, discussed below) is an invocation for the soul’s ascent from the bodily confinement, which enables it a more advanced form of existence:

And come forth from the cloud of unknowing

and kiss the cheek of the moon;

the New Jerusalem glowing [the code of solitude broken]

why tarry all night in the ruin? [why tarry confused and alone?]

And leave no word of discomfort,

and leave no observer to mourn,

but climb on your tears and be silent

like a rose on its ladder of thorns (“The Window”).

The “cloud of unknowing” is a clear reference to a 14th century book of Christian mysticism called The Cloud of Unknowing. The book is, in reality, a manual for a young adept who embarks on a spiritual journey. Entering the cloud means to lose any notion of one’s self and sensory perceptions. Only in this state caused by deep meditation and prayer one may leave the notion of one’s self behind and allow the soul to depart from its body.

The phrase “kiss the cheek of the moon” seems to be referring to the ascent and union with the lunar / feminine power. Here, it is apt to mention the masculine and feminine qualities of the G-dhead. Jewish, Christian, and even Islamic mysticism in general speaks about the nature of G-d as both masculine and feminine.[6] Without going deeper into these issues, one may simply state that G-d is not dual but its nature is masculine and feminine at once, at least to the mystic poets.

“The New Jerusalem glowing” symbolises the union of the soul with the Lord and its complete annihilation and rebirth. The reference could also imply that this “New Jerusalem” is the fulfilment of the covenant that manifests itself in one’s heart. The “Book of Revelation” says: “And I saw the holy city, the new Jerusalem, coming down from G-d out of heaven like a bride beautifully dressed for her husband” (NLT 21:2). Therefore, this “Jerusalem” might stand for a purified soul that is to descend back to the Earth into the human body.

In a complementary verse appearing in Cohen’s Stranger Music collection, the “New Jerusalem” is exchanged for the word “solitude,” which means that the solitude such as that lived by “Joan of Arc” is to be abandoned in order that love may be attained (299).

The soul is urged to climb on its suffering like a rose which climbs on its thorns before it blooms.[7] The “thorn” in the poem epitomizes human experience which, actually paves the way for the higher ascent and the appearance of the bloom. The “rose” symbolism in Christianity represents the drops of Christ’s blood during his ascent to the cross. Its contemporary notion stands obviously for passion and the fire of love. However, most importantly, it stands for life and death as it implies annihilation in love and rebirth. The descent of the soul is described as its rebirth in the body: “the word being made into flesh.” [End Page 7]

Then lay your rose on the fire;

the fire give up to the sun;

the sun give over to splendour

in the arms of the High Holy One

For the holy one dreams of a letter,

dreams of a letter’s death—

oh bless the continuous stutter

of the word being made into flesh (“The Window”).

In order for the rose / soul to bloom, she must pass through the period of solitude and longing and give herself to the fire, as in the song “Joan of Arc.” Therefore, the whole song might be seen as the instruction to the soul not to linger in the worldly realm but to ascend into the arms of the High Holy One, which echoes Kabbalah. The rest of the stanza indicates that the purified soul will be returned back into the flesh. That is why “the continuous stutter” is mentioned. This process is never ending because love triggers continuous rebirth, even as each individual instance of rebirth (each syllable in the stutter) also ends at some point.

Rūmī, the medieval Sufi mystic whom Cohen studied (Simmons 303), comments on the continuous rebirth by saying:

In the slaughter house of love, they kill

only the best, none of the weak or deformed.

Don’t run away from this dying.

Whoever’s not killed for love is dead meat (trans. Barks 270).

In other words, love and the willingness to “die” in love is the prerogative of “the best,” the elect, not of “the weak or deformed.” The Sufis encourage us to be part of this elect: to die for love and thus strive to have our souls purified. Cohen’s songs show this aspiration put into action.

In the above analysis of a few songs lyrics we have seen how Cohen portrays the union with G-d through various religious systems and how he uses symbolism coming from these religions in order to describe this divine phenomenon, which is not normally to be expressed in words but revealed to the initiates in sacred rites. Such is the case with the attainment of the new name, which, every time after being bestowed, stands for a renewed life which is one step higher than the previous existence. The next part of the essay will focus closely on the soul, its bodily sojourn, and the metaphor of its ascent through the imagery coming from the Kabbalistic and Alchemical teachings.

Kabbalah and Alchemy

Leonard Cohen has dedicated a great deal of work to portraying a man whose self and soul are divided and tormented, struggling against one another. This theme appeared in full in the book of psalms called Book of Mercy. In psalm III, Cohen offers a parable in which his [End Page 8] soul is singing against him and the effort of the self to reach that singing soul is painful and in vain:

I heard my soul singing behind a leaf, plucked the leaf, but then I heard it singing behind a veil. I tore the veil, but then I heard it singing behind a wall. I broke the wall, and I heard my soul singing against me. I built up the wall, mended the curtain, but I could not put back the leaf. I held it in my hand and I heard my soul singing mightily against me.

Although this particular psalm does not specify the soul’s complaint against the self—“this is what it is like to study without a friend,” the piece concludes—the Book of Mercy repeatedly describes vain efforts to reach the soul by our own effort and volition, rather than through the sort of patience which would prove our worthiness to receive love. Comfort and reassurance comes in those few psalms that show Cohen on more amicable terms with his suffering, willing to accept the fact that the preparation of the soul entails an almost unbearable degree of solitude and seclusion. I think here of psalm XVII, in which he addresses G-d with these words: “How strangely you prepare his soul” (referring to the loneliness before any union could take place); later in the volume, in psalm XLI, G-d responds that He is already present in the heart of the singer. “Bind me to you, I fall away. Bind me, ease of my heart, bind me to your love. […] And you say, I am in this heart, I and my name are here.” In Cohen’s theology―a synthesis of all the religious schools that Cohen studied, and perhaps one that comes out of his own experience―we see that G-d is present in the heart of the believer and to reach Him involves both self-criticism for one’s failures (“Blessed are you who speaks to the unworthy,” psalm XLI concludes) and the aspiration to be purified, the ascent of the liberated soul.

In the Sefirotic Tree, liberation is the outcome of reaching Da’at, a point in which other Sefirot unite or merge. This level allows the human soul, still perceiving itself as a soul, to receive the Divine spark and leads it to the most profound state of existence. According to Gareth Knight,

Da’at is the highest point of awareness of the human soul regarded as a soul (or in other terminologies Higher Self, Evolutionary Self, etc.) for awareness of the supernal levels can only be possible to the Spirit or Divine Spark itself. It is the gateway to what is called Nirvana in the East, and thus represents the point where a soul has reached the full stature of its evolutionary development, has attained perfect free will and can make the choice between going on to further evolution in other spheres or remaining to assist in the planetary Hierarchy (102).

In “New Jerusalem Glowing,” Eliot R. Wolfson quotes from Robert Charles Zaehner, a British scholar of Eastern religions, who describes the path of the mystic and his soul in terms of a bride who is annihilated in love of her Lord. The soul in such a state of existence is, according to Zaehner, very much aware of its “feminine” nature:

Zaehner describes the soul of the mystic in relation to the divine as the bride who passively receives from the masculine potency of God. The soul [End Page 9] recognizes its ‘essential femininity’ in relation to God, for in her receptivity, she is annihilated, which serves [. . .] as a paradigm of the mystical union whereby the autonomy of self is negated in the absorption of the soul in the oneness of being. Zaehner remarks that in this state the soul of the mystic, limited in his remarks to the male, is comparable to a ‘virgin who falls violently in love and desires nothing so much as to be ‘ravished’, ‘annihilated’, and ‘assimilated’ into the beloved (Wolfson 132).

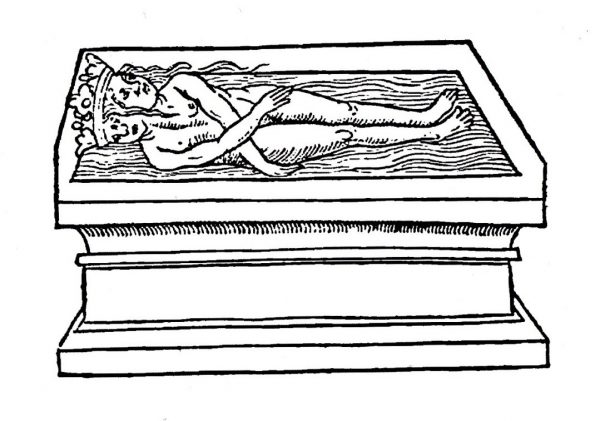

Both of the above quotations seem relevant to the work of Cohen, who in 1974 employed an engraving from an alchemical tract called Rosarium Philosophorum (published in Frankfurt in 1550) for the cover of his album New Skin for the Old Ceremony. The tract describes the alchemical process of transmutation of the human soul and the concrete picture depicts the union between the King and his Queen, or symbolically between the seeker and his purified soul.

The whole tract contains 20 engravings and an accompanying text describing the process of spiritual transformation by the means of the physical union. Milan Nakonečný, a Czech [End Page 10] scholar, claims that the act depicted aims to portray the union of opposites (coniunctio oppositorum) on the physical and also spiritual planes (152), but I would argue that it can also be read as depicting the return of the purified soul into the body blessed by the Holy Spirit, as in the third picture of the series, whose text reads “Spiritus est qui unificat.”

Paul D. MacLean, who is quoted in Nakonečný’s book, sees Rosarium philosphorum as a process in which the soul leaves the body in order to be purified, causing the body to decay, but which ultimately leads the soul back to the body: a reunion which restores harmony between the masculine and feminine divisions of a being (Nakonečný 153), reminding us of “the New Jerusalem glowing” mentioned earlier. Nakonečný compares this process to the “death” of a grain out of which develops a new ear of wheat (164);[8] he sees it portrayed in picture no. 6 of the series, in which the soul is being prepared for the leaving from the body and its subsequent return.

[End Page 11] The return of the purified soul into its body can also be seen in picture no. 10, described by Nakonečný as lapis philosophorum, which portrays a hermaphroditic being that has overcome its own death (as the dragon and serpent suggest) and represents the unity of the solar and lunar powers.

Here, we may remember the notion of the invisible sephirah Da’at, which means that the soul at this stage has reached the limits of its evolutionary possibilities. However, Cohen, by using the eleventh picture of the series for his album cover, suggests that he wants to go further. According to Nakonečný, this continuation of the ascent of the soul symbolizes transpersonal love towards one’s family, nation, or G-d (172). Hand in hand with this, Cohen portrays two angelic figures which are not going to undertake physical coniunctio because the Queen does not allow the King to lie between her legs. Although naked and lying on the top of one another, no penetration seems implied; rather, they seem primarily a reflection of one another. Eros in the picture is transmuted into another form of love, characterised by quenching bodily desires and nourishing the spiritual ones. Both represent the harmonic relationship between the purified soul and its reborn body.

With all of this in mind, the title and cover image of New Skin for the Old Ceremony become available for a variety of complementary meanings. From the Jewish point of view, the “old ceremony” implied in the very title of the album might be circumcision, that physical sign of a bond between the (male) Jew and G-d. The presence of “new skin” for this ceremony presages a new pact: one based on the human experience with love, betrayal, and [End Page 12] surrendering to G-d’s power as detailed in the songs on the album, rather than on the Biblical covenant. The songs themselves—which include “Lover, Lover, Lover,” discussed above, along with the famous “Chelsea Hotel #2,” “Who By Fire,” and “Take This Longing,” among others―speak by turns about love between two partners, carnal love and a complete abandonment of one’s own self and willingness to serve to G-d, but all are framed by the single image of the album’s cover, which casts them as aspects of or stages in a single process that includes both the spiritual and the carnal. In the next section we will see how Cohen acknowledges his own desire for the female body and what happens to love when he succumbs to it.

Human Love

Love portrayed by Cohen has for the ultimate goal to reach Divine union. However, he does not attain this union only through the spiritual exercise, but also through the sexual act. With regard to the union of opposites that we saw in Rosarium philosophorum and its physical description of spiritual processes, we may interpret sexual love and the subsequent “decay” of the body to be a precursor to the spiritual form of love and love for humanity which characterizes it. However, the work of the singer has not been consistent with this theme, as the spiritual exercise and sex interchange one another in a regular, cyclical way.

In the Key Arena in Seattle in 2012, Cohen, when introducing the song “Ain’t No Cure for Love,” acknowledged that sexual desire has been always winning him over:

I studied religious values. I actually bound myself to the mast of non-attachment, but the storms of desire snapped my bounds like a spoon through noodles (“Ain’t No Cure for Love”, live, YouTube).

“Ain’t No Cure for Love” is a song that was inspired by the spread of AIDS in 1980s. The story goes that Jenifer Warnes was walking with Cohen one day around his neighbourhood and they were discussing the fact that people would not stop making love with one another. Cohen ended the conversation by saying that “there ain’t no cure for love” meaning that there is no cure for people wanting to make love. Several weeks later he finished the lyrics and Warnes recorded the song for her album Famous Blue Raincoat in 1987 (Nadel 244). Cohen released his own recording of it on I’m Your Man the following year.

The fact that this song portrays longing for the woman, rather than for Divine love, is supported by the following verses: “I see you in the subway and I see you on the bus / I see you lying down with me, I see you waking up / I see your hand, I see your hair / Your bracelets and your brush / And I call to you, I call to you / But I don’t call soft enough.” The feminine character to whom he addresses these words is unresponsive. Then the singer wanders to an “empty church” and realises that his longing for the woman is of the same greatness as his longing for G-d (“Ain’t No Cure for Love”).

Cohen sings that he longs for nakedness, not only of the body but also of the soul: “I’d love to see you naked / In your body and your thought.” He refuses a brotherly form of attachment (philos): “I don’t want your brother love / I want that other love,” and repeats that he is not going to give up on his longing. However, in this song a longing for physical [End Page 13] union and the longing for union with G-d do not exclude each other and, if our supposition about the rebirth of the soul is right, we see a circle of constant purification and rebirth of which the sexual act might indeed be the first step. As discussed above, the sexual act ends the physical or interpersonal longing and commences the “decay” of the body in order that the soul could ascend and be purified. The end of the song contains the verse “And I even heard the angels declare it from above / There ain’t no cure, there ain’t no cure, there ain’t no cure for love,” thus ensuring us that the longing for the body of other person may be sanctified by G-d Himself (“Ain’t No Cure for Love”).

“Dance Me to the End of Love” can be read in the similar fashion since it describes not only the union of two lovers but also the ascent of the soul to G-d. The song is explained in this way through two accompanying videos. The first video, directed by Dominique Issermann in 1985, emphasizes the way that interhuman love works as a stage in the soul’s progress. It depicts, in a rather disconcerting manner, a woman who comes to the hospital to say the last goodbye to her male lover, played by Cohen himself. Only a moment later, Cohen’s ghost pursues the woman, both physically (by following after her through various wards in the hospital, and then, in a dream-like leap, watching her pose like a classical statue in a white shroud on a stage) and through his pleading voice. In the last part of the film, as Cohen sings, the woman disappears behind her shroud, as though breaking the bond of desire that held the singer to her, freeing him to move on to the next stage in his ascent. While this video emphasises love as a mystical union, the second piece―made in 1994 to promote the live album Leonard Cohen in Concert―is concerned with a sentimental depiction of romantic love between men and women. Featuring a multiracial set of couples at various ages—some older couples waltz in front of oversized portraits of themselves in their youth; one older woman waltzes alone in front of the picture of a man we assume is her lost lover, and other solitary figures gaze sadly at an empty chair—the video repeatedly cuts to a dapper, suited Cohen singing with his band and backup singers, a lady’s man and crooner rather than a spiritual seeker. Inviting these two contrasting visual interpretations, the song itself can be seen as portraying both divine and physical love, as though there were no necessary contradiction between them.

On the other hand, Cohen has criticised unrestrained human love that does not lead to the purification of the soul and which is characterised by inordinate lust and satisfaction of the basest instincts. He presented this criticism in the song “Closing Time,” which depicts a reverie in a country-like setting, with “Johnny Walker wisdom running high.” The feminine character of the song is described as the mistress who is “rubbing half the world against her thigh.” The whole binge is going to lead to its end sooner or later but before it happens, Cohen sings: “all the women tear their blouses off / and the men they dance on the polka dots / and it’s partner found and it’s partner lost / and it’s hell to pay when the fiddler stops / it’s CLOSING TIME.” Each stanza ends with the symbolic “CLOSING TIME” warning that this reverie is going to end soon. We do not know what happens later, whether the end will be revelatory or whether it will be a fall to an even profounder mire of bodily desires. Cohen speaks about the liminality, the threshold that we mentioned before, on which the whole event takes place: “I just don’t care what happens next / looks like freedom but it feels like death / it’s something in between, I guess / it’s CLOSING TIME.” Taken alone, “Closing Time” seems a portrait of frustration, since the singer seems trapped in the moment when “the gates of love they budged an inch” but “[he] can’t say [that] much has happened since.” In the context of the full album on which it appears (The Future), however, the song reads [End Page 14] differently. The bleak present and future that the songs here sometimes describe, in which “the blizzard of the world / Has crossed the threshold / And it has overturned / The order of the soul,” is what affords us the opportunity for and the drive to seek redemption. As Cohen sings on the album’s central track “Anthem:” “Every heart, every heart / to love will come / but like a refugee.” Love (divine Love, in this case) will be always there waiting for us, but we turn to come to it when other bonds and connections, romantic or political, have failed: when, like refugees, we do not have any other option.

The celebration of the union between two human lovers is a distinctive feature of Cohen’s oeuvre. Among the canonical songs that we have quoted so far one merits a special attention: the song “Hallelujah,” which portrays secular love between two partners as holy. The song addresses a “you” inspired by the Biblical King David (with touches of Samson mixed in) who in his piety let himself to be conquered by desire for the female body. In the chorus, Cohen consoles us that “There’s a blaze of light / In every word / It doesn’t matter which you heard / The holy or the broken Hallelujah,” meaning that G-d may be reached through sacred meditation or through sex as both lead to the union with Him. In the last stanza, the singer confesses that when he could not “feel”—feel the divine love—he had to “touch” the female body: “I did my best, it wasn’t much / I couldn’t feel, so I tried to touch.” Even if he fails in his devotion to G-d and later to his female partner as he confesses, he will be summoned by the Lord: “and even though / It all went wrong / I’ll stand before the Lord of Song / With nothing on my tongue but Hallelujah.” The song suggests that there is no difference between attaining Divine love through spiritual exercise or physical union. In one of the verses that Cohen occasionally sung live, he made this supposition quite clear: “remember when I moved in you / And the holy dove was moving too / And every breath we drew was hallelujah.”[9]

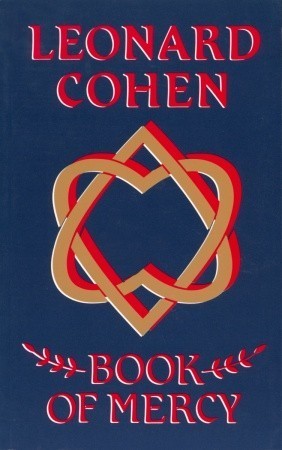

Order of the Unified Heart

Although he is better known as a songwriter, poet, and novelist, Cohen was also a visual artist. In order to promote the concept of a union between Divine and Human forms of love, Cohen created a symbol for his imagined “Order of the Unified Heart”: the Star of David made out of two intertwined hearts. These hearts stand as opposites to each other and are mutually dependent. One points to the Heavens while the other one points to the Earth. This motif first appeared on the cover of the collection of Psalms Book of Mercy. [End Page 15]

It is also mentioned in the song “Come Healing,” where Cohen sings: “The Heart beneath is teaching / To the broken Heart above.” The singer even made the two intertwined hearts the focus of the Priestly Blessing which the Jewish priests bestow upon the community and which he himself bestowed officially on September 24, 2009 at the Ramat Gan concert in Israel to an audience of around fifty thousand spectators.[10]

[End Page 16] The above picture of Cohen’s latest seal contains moreover the word Shin, which represents another name for G-d, Shaddai. Shin is formed by the priest’s hands when giving the Blessing and stands in between the two hearts. Therefore, the whole image represents the profane and sacred form of love at once blessed by the priest and proving that Cohen saw their intersection as the place where the Divine is made manifest.

Conclusion

“I don’t know a thing about love,” Cohen said in the interview with Pat Habron in 1973 (rpt. in Burger 50). More than twenty years later in 1997, when being interviewed by Stina Lundberg Dabrowski, he commented on the full realisation of the human existence in love and the possibility that it reconciles the opposing forces of our selves and paves the way to the liberation of the soul:

SLD: What is love to you?

LC: Love is that activity that makes the power of man and woman [. . .] that incorporates it into your own heart, where you can embody man and woman, when you can embody hell and heaven, when you can reconcile and [. . .] when man and woman becomes your content and you become her content, that’s love. That as I understand is love—that’s the mechanics (rpt. in Burger 420).

We have seen that Leonard Cohen portrays receiving of divine love through solitude and meditation and sexual intercourse. Love thus attained has the power to purify the soul and reunite it with its body in a greater spiritual existence. With the help of religious and mystical motifs, Cohen attributes sacred qualities to the Divine as well as Human love and, finally, consecrates it in his seal.

Love portrayed in such a way has, of course, been the subject of many medieval mystical books and appeared even visually in alchemy. Cohen’s acquaintance with religious and philosophical thought across cultures and continents is unsurpassed among the singer-songwriters in the English-speaking world, and his lyrics and choice of visual art for covers and merchandise show that he is keen to bring these enduring traditions to the attention of his audience.

As I have argued at length elsewhere, Cohen’s work draws on and gives new life to motifs that appeared in medieval love poetry, making him in every sense a “modern troubadour.”[11] Like the medieval poets of Provença and Al-Ándalus, he blurs the division between the sacred and profane, between the Divine and Human, and between the high and low forms of art and situates his work in the popular culture.

May this essay contribute to his honour.

[1] “Well you know that I love to live with you, / but you make me forget so very much. / I forget to pray for the angels / and then the angels forget to pray for us” (“So Long, Marianne”).[End Page 17]

[2] The full Shahada (testimony) goes: “lā ʾilāha ʾillā llāh muḥammadun rasūlu llāh.” (“There is no god except for Allah. Muhammad is the messenger of G-d”).

[3] A similar motif can be found in Christian mystical poetry. One may think only of San Juan de la Cruz (1542 – 1591) and his texts such as “Noche escura del alma,” “Cántico espiritual,” and “Llama de amor viva.”

[4] For an illustrative example, see, for instance, Ten Bulls, woodcuts by the Japanese artist Tokuriki Tomikichiro (1902 – 1999) in Shigematsu 6-23.

[5] I have written about love as a phenomenon initiating the singer into the sacred mysteries elsewhere (Měsíc, “The Song of Initiation”).

[6] This very ancient idea about non-duality of G-d may be found in the texts as old as Plato’s Symposium, for instance, from which many mystical schools drew. Important for the Jewish mystics is the verse from Genesis 1:27 “So God created man in his own image, / in the image of God he created him; / male and female he created them.” (ESV). Therefore, the male and female beings are the image of G-d because He is male and female at once. The Christian mystics refer to the same verse and some of them even go so far as to give preferences to the feminine atributes of G-d, such as Julian of Norwich (1342-1416) in her book Revelations. Muslims do not assign a gender to Allah. We should keep in mind that although the religious texts often address G-d with the use of masculine pronouns, verbs and nouns, G-d is regarded as gender and sexless. In Sufism they avoid using the grammatical gender by using the words Hu or Huwa to speak about the One.

[7] The rose is a very common symbol in Persian poetry, standing for Paradise and love (Baldock 142).

[8] This supposition, which appears in Alchemy, seems to be taken from the New Testament, and is seen in verses of John 12:24 “Truly, truly, I say to you, unless a grain of wheat falls into the earth and dies, it remains alone; but if it dies, it bears much fruit” (ESV). The death of Jesus brings fruit in the form of a new life multiplied by the number of grain on the ear: a metaphor for his followers.

[9] It can be heard, for instance, on the 2009 Live in London recording.

[10] For the full report, see Jeffay. The video of the blessing may be seen on YouTube: cf: “Leonard Cohen Finale in Israel – Priestly Blessing.”

[11] This theory was developed in my PhD thesis (Měsíc, “Leonard Cohen: The Modern Troubadour”). [End Page 18]

Bibliography

“Ain’t No Cure for Love.” Perf. Leonard Cohen, 2012. YouTube, uploaded by Arlene Dick, 10 November 2012, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b4R2-GlBd-c. Accessed 14 May 2015.

Baldock, John. The Essence of Rūmī. Chartwell, 2005.

Barks, Coleman, and Jalāl Ad-Dīn Rūmī. The Essential Rūmī: New Expanded Edition. HarperCollins, 2004.

Burger, Jeff. Leonard Cohen on Leonard Cohen: Interviews and Encounters. Chicago Review Press, 2014.

Cohen, Leonard. Beautiful Losers. 1966. New ed. Blue Door, 2009.

—. Book of Mercy. McClelland and Stewart, 1984.

—. Death of a Lady’s Man. 1978. New ed. Andre Deutsch, 2010.

—. Selected Poems: 1956-1968. Viking, 1968.

—. Stranger Music: Selected Poems and Songs. Vintage, 1994.

—. The Energy of Slaves. Cape, 1972.

Friedlander, Shems. The Whirling Dervishes. State University of New York Press, 1992.

Holt, Jason, editor. Leonard Cohen and Philosophy: Various Positions. Open Court, 2014.

Holy Bible: New Living Translation. Tyndale House, 2004.

Jeffay, Nathan. “‘Hallelujah’ in Tel Aviv: Leonard Cohen Energizes Diverse Crowd.” Jewish Daily Forward, Sept 25, 2009, http://forward.com/articles/115181/hallelujah-in-tel-aviv-leonard-cohen-energizes-di. Accessed 14 May 2015.

Julian. Julian of Norwich: Revelations, Motherhood of God. Edited by Frances Beer, D.S. Brewer, 1998.

Jung, C. G. Osobnost a přenos. Tomáš Janeček, 1998.

Khalil, Atif. “Ibn Al-‘Arabi on the Three Conditions of Tawba.” Islam and Christian-Muslim Relations, vol. 17, no. 4, 2006, pp. 403-16.

Knight, Gareth. A Practical Guide to Qabalistic Symbolism. S. Weiser, 1978.

“Leonard Cohen Finale in Israel – Priestly Blessing.” Perf. Leonard Cohen. YouTube, uploaded by Amit Slonim, Sept 29, 2009, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4imJ7wWB9FU. Accessed 14 May 2015.

Lumsden, Suzanne. “Leonard Cohen Wants the Unconditional Leadership in the World.” Winnipeg Free Press [Winnipeg], 12 Sept. 1970, p. 25. Newspaper Archive, http://newspaperarchive.com/ca/manitoba/winnipeg/winnipeg-free-press/1970/09-12/page-93>. Accessed 1 July 2014.

Matt, Daniel Chanan. The Essential Kabbalah: The Heart of Jewish Mysticism. Harper San Francisco, 1995.

Meier, Allison. “Drawings by a Ladies’ Man: Impressions of Leonard Cohen.” HYPERALLERGIC: Sensitive to Art and Its Discontents, 7 April 2015, https://hyperallergic.com/197029/drawings-of-a-ladies-man-impressions-of-leonard-cohen/. Accessed 19 April 2015.

Měsíc, Jiří. “The Song of Initiation by Leonard Cohen.” Ostrava Journal of English Philology, vol. 5, no. 1, 2013, pp. 69-93.

[End Page 19]

Měsíc, Jiří. “Leonard Cohen: The Modern Troubadour.” Dissertation, Palacký University, 2016. https://theses.cz/id/ksff70/Leonard_Cohen_The_Modern_Troubadour.pdf

Nadel, Ira Bruce. Various Positions: A Life of Leonard Cohen. University of Texas, 2007.

Nakonečný, Milan. Smaragdová deska Herma Trismegista. 2nd ed., Vodnář, 2009.

Robertson, Jenny. Praying with the English Mystics. Triangle/SPCK, 1990.

San Juan. San Juan de la Cruz: Poesía. Edited by Domingo Ynduráin. Cátedra, 2002.

Shigematsu, Sōiku. A Zen Forest: Sayings of the Masters. Weatherhill, 1981.

Simmons, Sylvie. I’m Your Man: The Life of Leonard Cohen. Jonathan Cape, 2012.

Spearing, A. C., trans. The Cloud of Unknowing and Other Works. Penguin, 2001.

The Holy Bible: Containing the Old and New Testaments Authorized King James Version. Thomas Nelson, 2011.

“The Window” Perf. Leonard Cohen. 1979. YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ejzXh0DDe0w. Accessed 12 April 2015.

Wolfson, Eliot R. “New Jerusalem Glowing: Songs and Poems of Leonard Cohen in a Kabbalistic Key.” Kabbalah: Journal for the Study of Jewish Mystical Texts, vol. 15, 2006, pp. 103-53.

Discography

Cohen, Leonard. Songs of Leonard Cohen. Rec. Aug. 1967. John Simon, 1967. CD.

—. “So Long, Marianne.” Songs of Leonard Cohen. Columbia, 1967. CD.

—. Songs from a Room. Rec. Oct. 1968. Bob Johnston, 1969. CD

—. Songs of Love and Hate. Rec. Sept. 1970. Bob Johnston, 1971. CD.

—. Live Songs. Rec. 1970, 1972. Bob Johnston, 1973. CD.

—. “Love Calls You by Your Name.” Songs of Love and Hate. Columbia, 1971. CD.

—. “Joan of Arc.” Songs of Love and Hate. Columbia, 1971. CD.

—. New Skin for the Old Ceremony. Rec. Feb. 1974. Leonard Cohen, John Lissauer, 1974. CD.

—. Death of a Ladies’ Man. Rec. June 1977. Phil Spector, 1977. CD.

—. Recent Songs. Rec. Apr. 1979. Leonard Cohen, Henry Lewy, 1979. CD.

—. “The Ballad of the Absent Mare.” Recent Songs. Columbia, 1979. CD.

—. “The Window. Recent Songs. Columbia, 1979. CD.

—. Various Positions. Rec. June 1984. John Lissauer, 1984. CD.

—. “Dance Me to the End of Love.” Various Positions. Columbia, 1984. CD.

—. “Hallelujah.” Various Positions. Columbia, 1984. CD.

—. Dear Heather. Rec. 1985, 2002 – 2004. Leanne Ungar, Sharon Robinson, Anjani Thomas, Henry Lewy, Leonard Cohen, 2004. CD.

—. I’m Your Man. Rec. Aug. 1987. Leonard Cohen, Roscoe Beck, Jean-Michel Reusser, Michel Robidoux, 1988. Vinyl recording.

—. “There Ain’t No Cure for Love.” I’m Your Man. Columbia, 1988. CD.

—. The Future. Rec. Jan. 1992. Leonard Cohen, Steve Lindsey, Bill Ginn, Leanne Ungar, Rebecca de Mornay, Yoav Goren, 1992. CD.

—. “Anthem.” The Future. Columbia, 1992. CD.

—. “Be for Real.” The Future. Columbia, 1992. CD.

—. “Closing Time.” The Future. Columbia, 1992. CD.

—. Ten New Songs. Sharon Robinson, 2001. CD.

[End Page 20]

—. “Boogie Street.” Ten New Songs. Columbia, 2001. CD.

—. “Light as the Breeze.” Ten New Songs. Columbia, 2001. CD.

—. “Love Itself.” Ten New Songs. Columbia, 2001. CD.

—. Old Ideas. Rec. 2007 – 2011. Patrick Leonard, 2012. CD.

—. “Hallelujah.” Live in London. Columbia, 2009. CD.

—. “Come Healing.” Old Ideas. Columbia, 2012. CD.

—. Can’t Forget. Rec. 2012-2013. Mark Vreeken and Ed Sanders, 2015. CD.

—. Popular Problems. Rec. 2014. Patrick Leonard, 2014. CD.

—. You Want It Darker. Rec. 2015-2016. Adam Cohen and Patrick Leonard, 2016. CD.

[End Page 21]