[End Page 1]

Introduction and Background

The romance genre is one of the bestselling genres in the United States (US). It is also the largest genre read in e-book (electronic book) format in the consumer market (RWA). An e-book format, for the purpose of this study, is defined as Adobe PDF, Mobipocket, Adobe EPUB, OverDrive Read and Kindle library downloads (OverDrive). The discovery of e-books and the growth of e-reading is rapidly increasing as more materials become available online and accessible on different technological devices. With this growth in e-reading, the demand for a diverse range of titles in e-book format is increasing. OverDrive, a global digital system that distributes e-books and other multimedia, offers the primary source for e-book library downloads. The Wisconsin Public Library Consortium (WPLC) currently has an OverDrive digital library (DL) of electronic materials for Wisconsin residents.

This exploratory case study examines how Wisconsin public libraries’ digital collections present a range of racial and ethnic perspectives and reflect the racial and ethnic demographics of their service communities by reviewing multicultural romance genre e-book title records in the WPLC digital library. Within this context, the study addresses the following questions: Do public libraries’ digital collections present a diversity of racial and ethnic perspectives and reflect the racial and ethnic demographics of their distinct service communities? What is the accessibility of these e-books within the digital system? This study analyzes the availability (number of titles, copies and holds) of the books as well as their accessibility (language selection and classification of titles) within the WPLC digital library system, determining whether the DL was supplying racially and ethnically diverse romance titles in e-book format and whether the e-books were accessible to potential users. The study also examines whether the DL is increasing the amount of these e-books in the collection to assist in the demand for the popular romance genre.

Romance Fiction and Multicultural Romance Fiction

Romance fiction has developed and expanded as a genre since its early beginnings. It is, by definition, a genre of literature that presents a fictional or legendary love story, tale, or prose narrative, which may include heroism, chivalry, adventure, and mysterious and/or supernatural elements (Merriam-Webster). Romance fiction writing and leisure reading has been a popular activity for centuries. Subgenres include historical, contemporary, paranormal, suspense, westerns, inspirational/religious, fantasy, and young adult romance (RWA). Romance novels specifically focus on relationships. They may contain varying sensuality degrees, from sweet to extremely hot (Bouricius 3-11). Readers can become involved on an emotional level with the story’s characters, experiencing a journey to a “Happily Ever After” that makes them feel satisfied at the end (Radway 61; Wendell 8). [End Page 2] Romance fiction has traditionally presented homogeneous representations of White, non-Hispanic characters, cultural traditions, and social values.

Multicultural romance fiction includes works written by authors who identify as Hispanic or Latina/o, Black or African American, American Indian or Alaska native, and/or Asian. It also includes romance fiction that depicts characters of color or indigenous characters and culturally diverse narratives, either by authors from that same racial/ethnic group or not (Bostic 214). The representations of characters of color or indigenous characters vary within romance fiction (and among other genre fiction), ranging from one-dimensional, stereotypical characters to characters with three-dimensional depth and realistic characteristics. The range contains problematic stereotyping of women of color and indigenous women as hypersexual, sexually aggressive, violent, or submissive sex objects in contemporary fiction (White 1-3; Gregor xiv). Characteristics of less educated people or those from lower socioeconomic classes have often been used to add “ethnic flavor” to stories (Forster paragraph 10). Narratives that interrupt and challenge such stories introduce more positive, relevant representations, highlighting culture, empowerment of families and communities, and a range of realities (White 7). Multicultural romance encompasses a variety of cultures, with the most frequent emphasis on African American romance (Ramsdell 290).

Authors of color and indigenous authors have been writing and publishing romance works for centuries, but it has only been within the past twenty years that they have benefited professionally and financially from such publications (White). Publishing companies did not publish African American authors’ romance fiction until the 1980s and only began introducing publications representing African American characters in the 1990s (White 6). Before this time, publications with African American and American Indian characters were rare (Osborne; Gregor 175-176). The early 1990s brought a boom in multicultural romance publications, with major publishing companies establishing specific multicultural imprints. In 1991, Ballantine was the first major publishing company to establish an imprint specifically focusing on multicultural books of “African-American, Asian, Latin, and Native American interest” (One World). In 1994, Kensington established “Arabesque Books,” an imprint focusing on African American romances (Osborne; White), and in 1999, “Encanto,” a line of “Hispanic contemporary romances.” The “Arabesque” imprint was sold to B.E.T. in 1998, which prohibited Kensington from publishing competing books. After this limitation was lifted, Kensington launched “Dafina” in 2000 “by and about people of the African descent” (Publishers Weekly, “Kensington Returns to African-American Market,” 1; Kensington Publishing Corp.). Furthermore, Harlequin developed Kimani Press, a division publishing mainstream fiction predominantly featuring African American characters, in 2005. Kimani now includes five distinct imprints (Harlequin; Reid). Harlequin also publishes Spanish translations in their “Bianca” and “Deseo” lines, which are popular romance novels written by White, non-Hispanic authors, featuring White, non-Hispanic characters (Engberg 237). Independent publishing companies have likewise committed to the publication of multicultural romance novels. Genesis Press, established in 1993, is the largest privately owned African American publishing company in the US. It has expanded to produce eight distinct imprints as well as classic and new books that are translated into Kiswahili. Parker Publishing is a small publishing company that was developed in 2005 to create literature for “Black and multi-ethnic readers,” including the Fire Opal line of publications (Parker Publishing). [End Page 3]

Encounters with literature that reflects one’s own experience, familiar settings, or recognizable themes can be empowering and validating. Encounters with literature that portrays a diverse range of representations and narratives can expand individuals’ worldviews. Librarians have the opportunity and the responsibility to facilitate such encounters by developing collections that portray diverse perspectives and representations, regardless of the local community (Bostic 216). Van Fleet in 2003 addressed the lack of diversity in popular fiction library collections by recognizing the failure to understand popular literature’s impact on social and personal validation (70). Library materials need to reflect the diversity of their service communities and present a diversity of ideas. These goals can be fulfilled through the development and maintenance of an e-book DL.

E-Books in Public Libraries

E-books range in format variety and are downloaded on an e-reader or other technological device (Pawlowski 58). While the first e-book became available in 1971 via the Internet DL Project Gutenberg, e-book commercialization in the late 1990s was a turning point for their current ubiquity and popularity (Galbraith). Downloadable audiobook availability in 2004 helped spur librarians’ interest in providing access to e-books in public libraries (Pawlowski 55). NetLibrary became the first e-book lending platform for libraries in 1998 (Galbraith), while current library e-book vendors include Baker & Taylor Axis 360, EBSCO eBooks, Gale Virtual Reference Library, Ingram MyiLibrary, OverDrive, ProQuest ebrary, and 3M Cloud Library (Blackwell et al. “ReadersFirst” 4). OverDrive is the highest ranked vendor for e-book services in libraries by ReadersFirst, a group of 292 library systems working to improve e-book access and services for public library users (3-6). OverDrive offers the most e-book format options for libraries (Pawlowski 61). Adobe EPUB, or “electronic publication,” is the current industry standard for e-books as developed by the International Digital Publishing Forum (Pawlowski 58-59). These e-books are accessible via e-readers, computers, handheld mobile devices, and tablets (Griffey 8; Library of Congress).

E-book popularity has been increasing in the last few years. There was triple digit growth in 2011 of e-book discovery and online readers due to the expanding use of digital devices and consumer awareness (Burleigh). E-book collections and overall demand have stabilized, yet a 2013 public library survey reported that e-book circulation in libraries has continued to rise (Enis, “Library E-book Usage,” 3). Keeping note of item usage can show how popular the item has been among users over a period of time (Wolfram 169). A 2012 Pew study of e-book usage illustrated that 21 percent of the American population has read an e-book (Rainie et al.). The most popular genre read in e-book downloads is romance (Veros 303). In 2011, OverDrive’s data from over five million users indicated romance was one of the top four genres searched in a DL (Reid). Libraries need to understand user habits to connect them to digital content (Menchaca 109).

Library development and maintenance of digital and print collections provides a diverse range of materials and formats for all users. Results from a 2013 PEW study indicates more than half of American participants definitely want more e-books offered as a library service (Zickuhr, Rainie and Purcell). With the increase in e-book availability and popularity, public library collection practices have changed to include print and digital [End Page 4] content (Bailey 57). Findings from a 2013 study showed that 89 percent of public libraries offer e-books to their patrons and a majority (also 89 percent) expect their e-book circulation to increase within the next year (Enis, “E-book Usage Survey,”3). A study tracking e-book circulation from 2004-2010 at the New York Public Library (NYPL) depicts an increase in patrons and e-book usage, with e-book usage disproportionately higher. A 2009-2010 NYPL e-book study showed that usage rose 37 percent and reported that library e-book users read digital content repeatedly (Platt 252). Libraries need to refine e-book services to accommodate users’ interests and needs. Public libraries provide collections of popular digital materials by working with a commercial vendor, rather than through a direct relationship with publishers (Pawlowski 56), which can present a cumbersome user experience (Blackwell et al. “ReadersFirst” 3). A PEW survey comparing e-book and print titles revealed 50 percent of library e-book borrowers feel there are long waiting lists and a lack of novel titles in e-book formats (Rainie and Duggan). While few studies have examined public libraries’ e-book services (Platt; Rainie and Duggan; Zickuhr, Rainie and Purcell), none specifically analyze racial and ethnic diversity within a public library’s e-book collection. This study explores diversity in the popular e-romance genre.

Library Policies and Philosophies

The Wisconsin state legislature’s policy for libraries states that libraries need to provide free access to information, a diversity of ideas, and knowledge, as well as providing electronic delivery of information, in order to maintain eligibility for state aid (Wisconsin Public Library Legislation and Funding Task Force; Wisconsin Statutes 43.00(a-b); Wisconsin Statutes 43.24(f-m)). Local policies and professional ethics drive public librarians’ commitment to providing materials that respond to community interests and needs, including racial, ethnic, and linguistic relevance and format interests.

The American Library Association Code of Ethics provides normative ethical guidelines for library and information professionals, beginning with, “We provide the highest level of service to all library users through appropriate and usefully organized resources; equitable service policies; equitable access; and accurate, unbiased, and courteous responses to all requests” (“Code of Ethics”). This principle recognizes the profession’s commitment to serving all library users with equitable access, without distinction based on race or ethnicity. Librarians have the opportunity as well as the obligation to provide encounters with e-books that reflect their diverse communities’ experiences and portray a diverse range of narratives with the potential to expand their worldviews.

E-book collection development

The WPLC mission is to provide Wisconsin residents with access to a broad, current, and popular collection of electronically published materials in a wide range of subjects and formats (Gold et al. “Collection Development Policy” 2). The Digital Library Steering Committee manages the WPLC digital library, including the development of policy and budget recommendations approved by the Board, decision-making for daily operations of the DL, and the establishment and management of a Selection Committee tasked with selecting materials for the DL. It is led by a member-selected Chair and membership is [End Page 5] comprised of one Board representative and one or more representatives from each partner, based on annual investment (Gold et al., “Members,” 2012).

The WPLC has a Digital Media Vendor/Product Selection Committee of eight members representing public library systems, individual libraries, the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction, and Wisconsin Interlibrary Services. This committee surveys the marketplace for products to support digital media material distribution in public libraries, develops criteria for WPLC vendor selection and contracts, and recommends a purchasing strategy for digital media to the WPLC Board (Bend et al. “Digital Media Vendor”). In 2011, the Vendor Selection Committee reported an “awareness of the inadequacy of the WPLC E-Book collection to cope with current demand” and a commitment to focus on offering “a rich collection of E-Books to public library patrons” (Bend et al. “Vendor Selection Committee”). The Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction Division for Libraries, Technology, and Community Learning organized an E-book Summit in 2012, which spurred WPLC organization of a statewide initiative to pool funds and purchase $1 million of e-books and audiobooks (Gold et al. “Collection Development Policy” 2). As of 26 April 2014, the WPLC digital library collection contains 9,433 romance e-book items, which has steadily increased by 505 items over the past two months.

Methods

The researchers in this study investigated how the WPLC digital library collection presents a range of racial and ethnic perspectives and reflects the racial and ethnic demographics of their service communities by conducting an exploratory case study with targeted searches for multicultural romance e-book authors and book titles in the WPLC digital library. A case study method was chosen to examine and better understand (Stake “Case Studies” 237) this particular DL and was the first phase of a longitudinal examination (Glesne 22). Future phases will include triangulation of multiple sources of evidence to validate findings (Stake “The Art of Case Study Research” 45).

Wisconsin Demographics

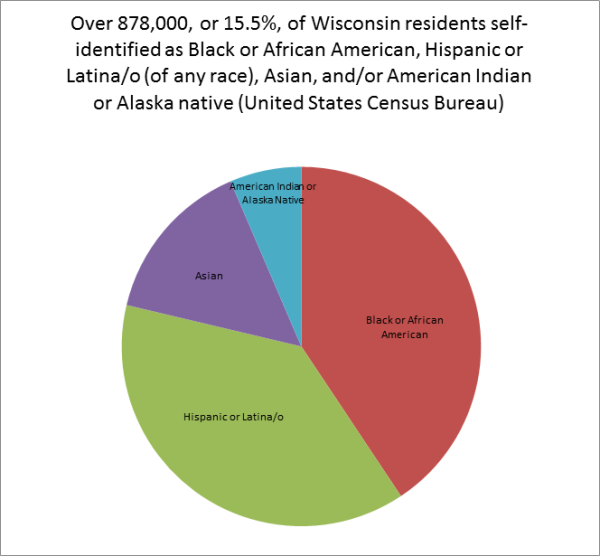

Out of the 5.6 million residents of Wisconsin, 878,000, or 15.5 percent, self-identified as Black or African American, Hispanic or Latina/o (of any race), Asian, and/or American Indian or Alaska native in 2010 (United States Census Bureau). Within this group, 6.3 percent of Wisconsin Census respondents identified as Black or African American, 5.9 percent identified as Hispanic or Latina/o (of any race), 2.3 percent identified as Asian, and 1 percent identified as American Indian or Alaska Native (see Fig.1). Additionally, 2.4 percent self-identified as some other race and 1.8 percent identified as two or more races. [End Page 6]

Wisconsin Public Library Consortium

The WPLC was formed in 2000 as a partnership of eight library systems and now includes 17 libraries and systems, covering almost all public libraries within the state (Gold et al. “For Patrons”; “Members”). WPLC focuses on increasing public access to information technology and digital materials through research, development, public awareness, library staff training, and public library cooperation (Gold et al. “About”). Advantages of consortium partnerships are vendor discounts, access to a larger breadth of titles, and less local spending on bestsellers that may quickly lose interest (Wisconsin Public Library Legislation and Funding Task Force; Schwartz, “OverDrive Data,” 6). The WPLC Collection Development Policy states its intention to “portray different viewpoints, values, philosophies, cultures, and religions in order to serve the varied statewide community” (Gold et al. “Collection Development Policy” 2).

Selection Process

The general descriptors for race and ethnicity by the US Census Bureau that are used as categories for exploration of multicultural romance e-books within the WPLC digital library are Black or African American, Hispanic or Latina/o, Asian, and/or American Indian or Alaska native. The researchers use the term multicultural to represent the collective racial and ethnic groups throughout this paper. The researchers explored a [End Page 7] variety of romance websites, wikis, and books to select a range of racially and ethnically diverse authors and book titles to include in the study.

The Reader’s Advisor Online website is based on the “Genreflecting Advisory Series,” a print book series published by Linworth Libraries Unlimited which is designed to help library staff with readers’ advisory, reference, and collection development in various fiction genres (Maas et al. “About”). The modular tab “Sample Core Collection” provides a recommendation list for basic romance collections, which includes a section for “ethnic/multicultural” authors and book titles organized under headings of “African American,” “Asian,” “Latino,” and “Native American (sometimes called ‘Indian’ in the trade)” (Maas et al. “Sample Core Collection”). The listing includes 31 authors, though the list might be used as a guide to be adapted and expanded to respond to the libraries’ specific needs. The modular tab “Publishers” lists trends in romance publishing and provides detailed information about various publishing companies and imprints, including Ballantine, Fawcett, One World, Genesis, Arabesque and Kensington (Maas et al. “Publishers”). The RT Book Reviews website is based on the RT Book Reviews Magazine that feature reviews of romance novel published along with blogs, news, awards, upcoming releases and themed booklists (Romance, “RT Book Reviews”). The website lists two themed (Asian and Native American) titles and a list of titles by author as recommended reads in 1999 and 2001 respectively (RT Book Reviews Themes: “Asian”; “Native American”). The All About Romance website consists of reviews, blogs, lists and features from readers and romance writers. The website offers a compiled list of Native American titles and authors from 2001-2007 (“American Indian Romances”). The Goodreads website includes options for a reader to find and share books as well as to create an account to keep track of personal books wanted or read (Chandler). Under the modular tab “Genre” is African American Romance, consisting of Most read this week titles tagged African American Romance and Popular African American romance books (“African American Romance”). These books are compilations from reader tags where contributors review books and place information on the website. The RomanceWiki website is based on the premise of Wikipedia, where anyone can contribute to the website. Booksquare.com, a leading literary blog, produces it. The website contains a range of information, featuring romance history and today’s leading romance bestsellers as well as reviews, books, publishers, authors, and articles of the romance genre (Simpson). Different categories in the RomanceWiki include information on titles, authors and publishers under the different category names. The categories examined on the website were African American, Chica Lit, Cuban-American Authors, Interracial Romance, Latina, Latina Lit, and Multi-Cultural (“Romance Sub-Genres”). The authors and book titles from these resources are categorized for inclusion in this study.

Results

Study results were analyzed by examining the history (Huberman and Miles 436) of the collection, including availability and accessibility of titles within the WPLC. Data was then scrutinized for underlying themes or patterns and clustered into meaningful groups (Creswell 101). [End Page 8]

Availability

A total of 151 individual authors in the study identified as Black or African American, Hispanic or Latina/o, Asian, and/or American Indian or Alaska native; or as authors who write multicultural romance fiction. A total of 153 individual book titles were identified as Black or African American romance book titles, Hispanic or Latina/o romance book titles, Asian romance book titles with settings in China, Hong Kong, Japan, Korea, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam, or historical and contemporary American Indian romance book titles. The researchers searched for each author and title individually in the WPLC digital library between 12 February 2014 and 26 April 2014. Keyword searches were conducted for authors’ names and book titles. Search results were limited to e-books, excluding some available audiobooks by selected authors.

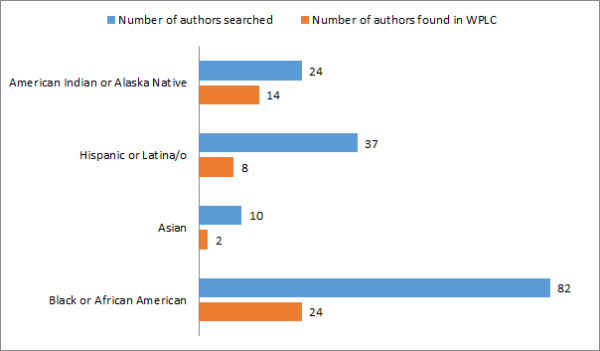

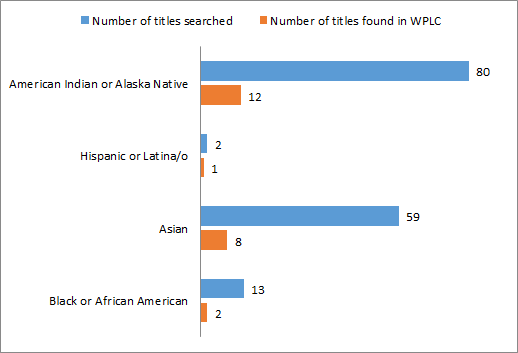

The results of these searches returned records for individual author titles and records for multiple author titles. In some cases, the catalog had multiple records of the same title, such as when WPLC digital library purchased copies of a title and partner libraries purchased additional copies of the same title for exclusive use by their local library cardholders. Additionally, 29.8 percent of the authors had e-book titles (see Fig. 2) and 15.7 percent of the individual book titles were available in e-book format within the WPLC digital library (see Fig. 3). [End Page 9]

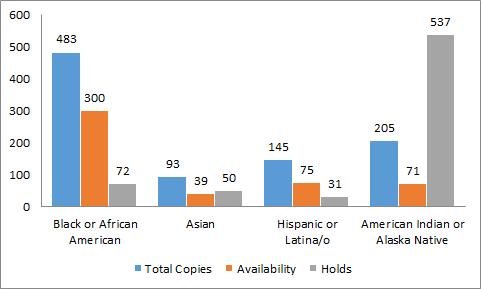

Data for each search includes the number of e-book titles present in the WPLC digital library; the number of copies of each title, the number of holds on each title, and the number of available copies of each title (see Fig. 4). Additional data includes subject headings (e.g., romance, fiction, African American fiction, historical fiction, urban fiction) and e-book format (e.g., Kindle, Overdrive, Adobe EPUB, Adobe PDF).

| Racial or ethnic group | Author | Number of titles | Number of copies of each title | Number of holds on each title | Number of available copies of each title |

| Black or African American | Alers, Rochelle | 18 | 2 2 2 … |

0 0 0 … |

0 2 1 … |

Figure 4: Example of monthly data collection.

Additionally, the researchers found that in February 2014, at least 10.3 percent of the WPLC romance e-book collection was multicultural romance e-books, and in April 2014, 10.2 percent of the total romance collection was multicultural romance e-books. The total of multicultural romance e-book records (i.e., individual authors, individual titles, and titles by multiple authors) in the collection in February 2014 was 430 items and 926 copies, which increased by 19 items and 41 copies over the two-month study period. There [End Page 10] were likely additional multicultural romance e-books within the WPLC digital library that were not found in this study because of the limited selection of multicultural romance authors and book titles.

The WPLC digital library provides a range of formats for the multicultural romance e-books. The e-books are available in four different formats, Kindle, Overdrive READ, Adobe EPUB, and Adobe PDF. The findings reveal the first three formats presented balanced numbers, while the lowest availability was in Adobe PDF format. The Library of Congress states that a PDF format is widely used among individuals, so e-books presented in Adobe PDF might be accessible to a greater population. However, there can be limitations with Adobe PDF because the fixed layout can make it difficult to adjust text size. The WPLC digital library provides a balanced number of options, facilitating access to the multicultural romance e-books for current and potential users.

The researchers found that there were an adequate number of copies of multicultural romance e-books available to respond to user interest and appeal to potential users. Most of the multicultural romance titles listed two copies available at a time. One person may check out a copy of the title for seven to twenty-one days, depending on the format. All items are available for at least seven days and Kindle, Adobe EPUB, and Adobe PDF may be checked out for seven, fourteen, or twenty-one days (WPLC). If an item is not available, users may place a hold on the item that prompts the system to send an alert when the item is returned by the previous user and available for checkout. Using NVivo data analysis software, the researchers conducted a text query for all holds and found that 82.6 percent had zero holds on the item, while the next highest holds were one (6.2 percent) and two (2.1 percent). The highest hold was eighty-one, but that was on a single item in one month. This outlier might have affected the results, which show that 78 percent of the holds are on American Indian records (see Fig. 5).

Data in February 2014 (see Fig. 5) depicted that the majority of the multicultural romance copies are Black or African American romance e-books. This aligns with Ramsdell’s point that there is a current emphasis on African American romances over other [End Page 11] racial or ethnic representations (290). The majority of the multicultural romance e-book titles are Black or African American, which is not proportionate to the percentage of Hispanic or Latina/o residents in Wisconsin. Further, each racial/ethnic category is diverse (e.g., nationality, culture, language, and religion) which may or may not be represented within the findings. For example, the majority of Wisconsin residents who identify as Hispanic or Latina/o also identify as Mexican (72.8 percent), followed by Puerto Rican (13.5 percent) (United States Census Bureau). These findings do not reveal the specific representation of distinct racial and ethnic groups in Wisconsin.

Item availability and holds influence the other, meaning if there are holds on the items, their availability decreases. Within the WPLC, the availability and hold status for each item is quite fluid and can change at any given time because the DL is a consortium of 17 libraries with library cardholders accessing the system 24/7. For example, this study shows a significant difference between the relatively low number and availability of American Indian books and the high number of holds for this category. This may be because of the mainstream popularity of authors who primarily write about White, non-Hispanic characters, and happen to have one or more books with characters who are American Indian. This may also simply be because American Indian stories were particularly popular at the time of the study. Romance readers can be loyal and may want to read everything by their favorite author (Bouricius 29) or might pick up a certain book because it is what they want to read at that particular time. This data is a snapshot of the multicultural romance e-books from February to April 2014. When comparing the three total data sets with the same totals compiled over the following two months, the researchers found there was not a significant increase or decrease in the percentage of total number of copies, item availability, or the number of holds with the percentage range of 5 percent or less for all of the racial and ethnic categories. More research needs to be undertaken to explore the data sets over a longer period to determine if the data remains constant within each racial and ethnic category.

Accessibility

Digital library materials need to be accessible to users with a range of information seeking behavior. A library user’s information needs, interests, and information seeking behavior can vary due to “cultural experiences, language, level of literacy, socioeconomic status, education, level of acculturation and value system” (Liu 124). In addition to exploring the availability of multicultural romance e-books, the researchers conducted advanced searches to investigate the accessibility of multicultural romance e-books. These searches were for all romance e-books available in languages other than English, and all romance e-books under the subject headings, “Multi-Cultural” and “African American Fiction.” Search results were limited to e-books, excluding some available audiobooks.

The WPLC digital library collection offers a minimal selection of romance e-books in languages other than English and the DL interface does not accommodate users that speak languages other than English. In February 2014, the collection contained 11 Spanish romance e-book title records, which increased by four items over the following two months. A German language romance e-book was added in March. While the WPLC digital library also contains materials in Arabic, Chinese, Czech, French, Greek, Hebrew, Italian, Japanese, Romanian, Russian, Swahili, and Swedish, there were no romance e-book titles [End Page 12] found in those respective languages. The DL interface is in English and does not offer any options to change the interface to any other language. The advanced search tools provide access to the limited number of materials in languages other than English, yet access to this search tool is restricted by the tools’ exclusive English accessibility. The records that contain words or names in languages other than English are not consistently precise in their presentation. For example, the Latina author Caridad Piñeiro, a.k.a. Caridad Piñeiro Scordato, is listed as “Caridad Pineiro” and “Caridad Pi¤eiro,” neither record accurately representing the ñ in her name. These factors limit the accessibility for users that speak languages other than English or records for materials containing words or names in languages other than English. At the February 2014 WPLC Digital Library Steering Committee Meeting, members agreed on the future discussion item “Multi language interface: Selecting titles in languages other than English” (Gold et al. “Steering Committee Minutes”). Improvement in this area might make the multilingual materials accessible to users that speak and read languages other than English.

The limited subject headings to classify materials within the WPLC digital library present barriers to accessing racially and ethnically diverse romance e-books. The researchers found an advanced search limited to subject headings “Multi-Cultural” and “Romance” returned zero titles between February and April 2014. Only one subject heading, “African American Fiction,” was used to identify racial or ethnic subjects within romance e-books materials. The only other relevant subject heading, “Multi-Cultural”, was not attached to any of the romance e-books. Print materials need to be physically arranged within a particular section of the library, while digital materials such as e-books do not have such limitations. Additional subject headings might increase the accessibility of digital materials. For example, classifications of the Latina/o romance e-books subject headings were limited to Fiction, Romance, Suspense, Short Stories, Erotic Literature, Fantasy, and Western. There is an invisibility of the range of racial and ethnic diversity represented within the DL collection that is a barrier to the accessibility of multicultural romance e-books.

Implications

Access and general issues

System usability is important in the discovery of and access to e-books. If a user is discouraged or disappointed with a search, it can lead to unsuccessful interactions with the system, leaving users unsatisfied (Xie 140). As stated earlier, accessing information from a DL can be challenging for users since some users are familiar with a traditional library of print books on shelves to browse titles (Lesk 204). This poses challenges for libraries to design an accessible system interface since there are many complexities to making digital items available and readily accessible for the online user (Van Riel, Fowler and Downes 244). Further research is needed to examine if the design of the WPLC digital library is a factor in current and potential users’ barriers to e-book access.

There can be additional accessibility issues that hinder users’ interactions with a system. These barriers are not covered in the scope of this study, but are explained briefly [End Page 13] here. Being a novice or expert user can determine the success a user experiences when searching in an online system. Users can have more difficulty finding or retrieving desired information if they have less experience with the system. In addition, a user’s information literacy or digital literacy skills can determine how well the user accesses materials within an online system. The fewer skills users have in understanding how to use a system, the less successful the interaction. Another possible issue is connectivity. Users might not have broadband access at home due to lack of infrastructure or affordability. Internet accessibility issues directly affect users’ access to online systems. If users have limited access to the Internet at home, they might rely on institutions, such as public libraries, to provide the access they need to find information.

Relationships between libraries and vendors

Publishers’ licensing agreements and commercial vendors’ policies limit the number and range of e-books. In 2013, “half of the big six publishers did not allow their e-books to be licensed by public libraries. Since then, Penguin has stated they will begin licensing e-books to OverDrive” (Enis, “Library E-book Usage,” 5). The WPLC Collection Development Policy explains how the selection criteria is based on the availability of titles from vendors (2), since some titles are not accessible for acquisition as a result of publishers’ limitations on digital editions of titles or limited embargos on new titles. The publishers might unexpectedly pull other titles from the collection (3). There are additional limitations on the DL collection from commercial vendors. OverDrive allows independent authors to submit titles for inclusion in DLs only if they have at least ten titles available. If authors have fewer books, it is recommended they work with an aggregator who can represent the independent authors as a collective. WPLC digital library contracts with OverDrive to follow these policies. If a local author wishes to add an e-book to the collection, it must be made available to all OverDrive DLs in the US. This can be beneficial to authors since Zickuhr et al. explained that 41 percent of users who read a library e-book are more likely to purchase their most recent e-book. However, OverDrive’s policies present independent authors barriers to making their works available. The option for libraries to increase their collections with items from individual authors can increase the collection by satisfying the demand for more titles, user-requested titles, and more multicultural romance titles by authors who are not represented by large publishing companies.

Commercial vendors hold the control over DL interface design and subject heading maintenance, which limits libraries’ system management. The vendors determine the options for e-book content and management systems for necessary or optional adoption by the contracted libraries. For example, in 2013, OverDrive announced its multilingual interface options in French Canadian, Simplified Chinese, and Spanish with plans to develop Japanese, Traditional Chinese, and additional language options. It was not possible for individual libraries to provide a multilingual interface before it was available through OverDrive. Additionally, libraries cannot customize the subject headings of their own DL collection records. The options to add or remove subject headings for specific titles through OverDrive is possible, yet it is necessary for OverDrive to receive multiple recommendations for subject heading changes before they make global changes to the record (OverDrive Partners). Collective groups of librarians, like ReadersFirst, work to improve users’ e-book access and public library services by addressing barriers to access to [End Page 14] e-books because of external issues related to publishing companies and commercial vendors.

Barriers

The greatest barrier to developing or expanding e-book collections has been funding limitations, although there has been a lack of interest in some cases (Enis, “E-book Usage Survey” 3). Ashcroft mentions how licensing and costs are issues that continue to be a problem in regards to library e-books (405). While financial constraints can leave libraries in a dilemma, multicultural fiction might not be considered a “special” acquisition, since these might be the first items omitted during budget cuts (Bostic 210). Multicultural fiction might be a constant component of libraries’ offerings that requires careful selection and maintenance. A 2013 survey of public libraries reports 42 percent of Midwest libraries state they might purchase e-books, but it was not a priority (Enis, “E-book Usage Survey” 23). This data might foretell future barriers in regards to e-book collection development.

Selecting materials for a library collection involves the library, the library patrons, and an understanding of the literature available (Van Fleet 78). The WPLC Selection Committee is comprised of two representatives from each of the partner libraries, divided into 24 selectors for adult materials and 10 selectors for young adult and children’s materials (Gold et al. “Selection Committee”). According to the 2014 collection development policy, selectors refer to reviews in professional journals, lists of recommended or award-winning titles, and other selection resources to inform their decisions (Gold et al. “Collection Development Policy” 3). Similar to recommending books to library patrons, a librarian needs to have knowledge of the literature and know what appeals to the patrons. Talking to the patrons to gain a sense of the community needs in turn guides the policy and procedures in acquiring the content for the collection (Gold et al. “Collection Development Policy” 73). George Watson Cole points out that “the library is in existence by the grace of the public, and it is a duty to cater to all the classes that go towards making up the community in which it is established” (qtd. in Bouricius 36, emphasis in original). Community interest, anticipated interest, individual requests and reports of satisfaction related to authors, titles, or subjects, are considered important to the WPLC selectors (Gold et al. “Collection Development Policy” 2). Libraries need to focus more attention on collaborative community assessments rather than library use studies alone, particularly to improve library services for racially and ethnically diverse communities (Bostic 217; Liu 131; McCleer 271). It is challenging for libraries to make an informed choice about collection development without knowing the interests, needs or concerns of the users (Ashcroft 399). Continued research needs to explore how the WPLC digital library conducts community assessment and analyses to inform their collection development.

With the popularity of the romance genre, more attention needs to be given to digital collection development of multicultural romance e-books. According to PEW in 2012, 56 percent of respondents specified that their library did not carry the e-book they wanted to borrow, which might be because the libraries are still building their digital collections (Zickuhr et al. “Libraries, Patrons and E-books.”). Moyer states libraries need to acquire different types of novels to give options to readers’ varied interests (230). Most romance readers enjoy reading a new book by their favorite author (Bouricius 47), so [End Page 15] varieties of romance novels are important to have in the collection. Beyond the limited availability and limited funds for multicultural romance fiction, acquisitions librarians must also work to select materials that present accurate representations of the diverse realities of individuals and communities of all races and ethnicities, taking care to recognize materials with subtle and overtly racist or discriminatory representations (Bostic 218). These limitations relate to users and systems that are compounded by external barriers, which affect the accessibility of multicultural romance e-books.

Future Research

This study reveals the current multicultural romance e-book titles’ availability and accessibility within the WPLC digital library. Some of the challenges to diminishing availability and accessibility barriers can be addressed by the WPLC digital library. However, there are challenges presented by external sources: for example, the available subject headings can be limited by the OverDrive system and publishing companies can limit the available e-books. An advanced search in the WPLC digital library for the African American independent publishing house Genesis Press, Inc. returns only one listing. Such limited availability can be a barrier for all romance e-books and for e-books in general. Further research will distinguish the sources for such challenges as well as opportunities for improvement. Interviews with WPLC librarians, particularly Selection Committee members, might provide further insight to the barriers to selecting and purchasing multicultural romance e-books for the DL.

The racially and ethnically diverse authors and book titles selected for this study were gleaned from a variety of romance websites, wikis, and books. Data analysis illustrates that some of the included authors are White, non-Hispanic authors who might have only one or two titles that include characters of color or indigenous representations, which is why they are listed in the various websites, wikis, and book resources for multicultural romances. Further research methods need to refine this selection process by removing these outliers from the data sets. The book titles need to be explored, rather than the individual authors’ comprehensive offerings in the DL. The selection in this study includes predominantly female authors. Future studies need to add male authors, such as African American authors Timmothy B. McCann, Colin Channer, Omar Tyree, Eric Jerome Dickey, Jervey Tervalon, E. Lynn Harris, Franklin White, and Van Whitfield (Cook 1; Rosen 38). Gay and Lesbian romance novels appeal not only to the homosexual reader but can also be of interest to heterosexual readers (Maas et al. “Gay and Lesbian Romance”). A search for “Gay/Lesbian” and “Romance” limited to e-books returns one title in the WPLC collection. Future studies need to specifically include the accessibility of various perspectives of sexuality and gender in romance e-books. Another search refinement needs to focus on how well a digital library presents complete book series (e.g., Brenda Jackson’s “Bachelors in Demand” series contains three out of the four titles).

An advanced search limited to the subject heading “Urban Fiction” resulted in 116 titles in February and increased by 13 titles over the following two months. Urban Fiction, also known as “Street Lit”, is set in a predominantly city landscape with plots delving into the realities and culture of the characters. It is traditionally a genre written by and for African Americans, though there are also urban Latino fiction novels and it is branching out into different sub-genres (Morris 2, 43). The search for urban fiction narrowed by the [End Page 16] subject heading “Romance” returned 20 titles consistently over two months. While some of these 20 titles were Black or African American romance titles, not all urban fiction romance can be categorized as multicultural romance. Further research needs to focus on this subject heading specifically within the DL.

Further studies of multicultural romance e-book accessibility needs to explore items found through the process of browsing. In 2012, OverDrive reported that nearly 60 percent of readers rely on browsing practices to encounter new e-books instead of searching for specific titles, and romance is the most popular genre for browsing (Schwartz). In this study, several items were added to the data sets because of the researchers’ browsing within the WPLC digital library, but this was not an intentional research method. A study designed around browsing digital collections might further explore multicultural romance e-book availability and accessibility.

This exploratory study provides a snapshot of the multicultural romance e-book availability and accessibility in the WPLC collection. Expanding studies in this DL can give area libraries a more comprehensive understanding of the WPLC multicultural romance e-book collection and identify specific areas that need improvement or refinement. A continuation of this exploratory study to include data over an entire year will establish a record of increases or decreases of multicultural romance e-books over a significant period. This data will be beneficial to discover patterns in collection development for distinct racial and ethnic groups.

Conclusion

This exploratory study finds that the WPLC digital library provides a foundational collection of multicultural romance e-books, which presents a range of racial and ethnic perspectives and provides a general representation of the racial and ethnic demographics of Wisconsin. In 2010, a total of 15.5 percent of Wisconsin residents identified as Black or African American, Hispanic or Latina/o, Asian, and/or American Indian or Alaska native (United States Census Bureau), and 10.3 percent of the entire WPLC romance e-book collection were multicultural romance e-books. The findings do not precisely align with the specific racial and ethnic demographics of Wisconsin. The multicultural romance e-books in the WPLC digital library present an adequate number and range of formats, which is beneficial to user access and appeal to potential users. The barriers to the accessibility of these items are related to language, subject headings, and system interface. Further research will explore the source of these barriers and opportunities for refinement. Overall, the WPLC has developed a solid foundation for fulfilling their mission to provide Wisconsin residents with access to a broad, current, and popular collection of electronically published materials in a wide range of subjects and formats. Continued development of the multicultural romance e-book collection will enhance their public library services to all of the 5.6 million Wisconsin residents with an interest in romance fiction. [End Page 17]

Works Cited

“About One World.” One World. n.d. Web. 7 April 2014.

“About Parker Publishing.” Parker Publishing. n.d. Web. 7 April 2014.

“About Us.” Genesis Press. n.d. Web. 7 April 2014.

“African American Romance.” Goodreads. n.d. Web. 24 November 2013.

“American Indian Romances.” All About Romance. 1 January 2014. Web. 2 February 2014.

“Asian.” RT Book Reviews. 1999. Web. 2 February 2014.

Ashcroft, Linda. “Ebooks in Libraries: An Overview of the Current Situation.” Library Management, 32.6-7 (2011): 398-407. Web. 15 March 2012.

Bailey, Timothy P. “Electronic Book Usage at a Master’s Level I University: A Longitudinal Study.” The Journal of Academic Librarianship 32.1 (2006): 52-59. Web. 8 December 2012.

Bend, Evan, Dale Cropper, John DeBacher, Noreen Fish, Jeff Gilderson-Duwe, Sara Gold, Mellanie Mercier, and Molly Warren. “Digital Media Vendor/Product Selection Committee.” Wisconsin Public Library Consortium (WPLC). 10 July 2013. Web. 9 April 2014.

—. “Vendor Selection Committee Report.” Wisconsin Public Library Consortium (WPLC). 2 November 2011. Web. 9 April 2014.

Blackwell, Michael, Christina de Castell, Ferriss, Thomas Lide, Sam Rubin, and Michael Santangelo. “ReadersFirst Guide to Library E-Book Vendors: Giving librarians the knowledge to be more effective e-book providers.” ReadersFirst. January 2014. Web. 10 July 2015.

Bostic, Mary. “Perspectives on Multicultural Acquisitions.” The Acquisitions Librarian 7.13-14 (1995): 209-222. Web. 7 April 2014.

Bouricius, Ann. The Romance Readers’ Advisory: The Librarian’s Guide to Love in the Stacks. Chicago: American Library Association, 2000. Print.

Burleigh, David. “Ebook Discovery and Sampling Skyrocketing at Public Libraries: OverDrive Digital Catalogs Connect Millions of Readers with Authors and Titles.” OverDrive. 19 January 2012. Web. 10 December 2012.

Chandler, Otis. “About Goodreads.” Goodreads. n.d. Web. 24 November 2013.

“Code of Ethics of the American Library Association.” American Library Association (ALA). 22 January 2008. Web. 8 April 2014.

Cook, Dara. “Real Men Read, Write, and Publish Romance: A Male’s Perspective.” Black Issues Book Review 1.4 (1999): 45. Web. 10 April 2014.

Corbin, Juliet and Anselm Strauss. “Grounded Theory Research: Procedures, Canons and Evaluative Criteria.” Qualitative Sociology 13.1 (1990): 3-21. Web. 10 February 2015.

Creswell, John. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. 4th edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2013. Print.

“Demographic Profile Data.” United States Census Bureau. 2010. Web. 14 November 2013.

“Device Resource Center.” OverDrive. 2012. Web. 8 April 2014.

“Devices and Formats.” Library of Congress: Web Guides. 23 September 2011. Web. 19 April 2014.

[End Page 18]

Engberg, Gillian. “Choosing Adult Romances for Teens.” Booklist 101 (2004): 237. Web. 7 April 2014.

Enis, Matt. “Ebook Usage Survey in U.S. Public Libraries: Fourth Annual Survey.” Library Journal. 2013. Web. 24 April 2014.

Forster, Gwynne. “Culture and Ethnicity: The African-American Romance Novel.” Affaire de Coeur Book Review Magazine (1997). Web. 7 April 2014.

Galbraith, James. “E-books on the Internet.” No Shelf Required: E-books in Libraries. Ed. Sue Polanka. Chicago: American Library Association, 2010. 1-18. Print.

Glesne, Corrine. Becoming Qualitative Researchers. 4th edition. Boston: Pearson, 2011. Print.

Gold, Sara, Stef Morill, Joy Schwarz and Bruce Smith. “About.” Wisconsin Public Library Consortium (WPLC). 6 July 2010. Web. 10 April 2014.

—. “Collection Development Policy.” Wisconsin Public Library Consortium (WPLC). December 2011. Web. 10 April 2014.

—. “For Patrons.” Wisconsin Public Library Consortium (WPLC). 12 March 2012. Web. 9 April 2014.

—. “Members.” Wisconsin Public Library Consortium (WPLC). 30 November 2012. Web. 10 April 2014.

—. “Selection Committee.” Wisconsin Public Library Consortium (WPLC). 18 December 2013. Web. 10 April 2014.

Gregor, Theresa Lynn. From Captors to Captives: American Indian Responses to Popular American Narrative Forms. Diss. University of Southern California, 2010. Ann Arbor: UMI, 2010. Web. 7 April 2014.

Griffey, Jason. “Chapter 2: Electronic Book Readers.” Library Technology Reports 46.3 (2010): 7-19. Web. 12 March 2012.

Huberman, A. Michael and Matthew B. Miles. “Data Management and Analysis Methods.” Handbook of Qualitative Research. Ed. David O’Brien. California: SAGE Publications, 1994. 428-444. Print.

“Imprints.” Kensington Publishing Corp. 2014. Web. 11 April 2014.

“Kensington Returns to African-American Market.” PW: Publishers Weekly 250.42 (20 October 2003): 12. Web. 7 April 2014.

“Kimani Press.” Harlequin. 2013. Web. 7 April 2014.

Lesk, Michael. Understanding Digital Libraries. 2nd edition. Amsterdam: Morgan Kaufmann Publishers, 2005. Print.

Liu, Mengxiong. “Ethnicity and Information Seeking.” The Reference Librarian 23.49-50 (1995): 123-134. Web. 8 April 2014.

Maas, Ron, Barbara Ittner, Laura Calderone and Birgitte Elbek. “About the Reader’s Advisor Online.” The Reader’s Advisor Online. 2006. Web. 11 April 2013.

—. “Publishers”. The Reader’s Advisor Online. 2006. Web. 6 February 2014.

—. “Sample Core Collection.” The Reader’s Advisor Online. 2006. Web. 24 November 2013.

McCleer, Adriana. “Knowing Communities: A Review of Community Assessment Literature.” Public Library Quarterly 32.3 (2013): 263-274. Web. 30 April 2014.

Menchaca, Frank. “Funes and the Search Engine.” Journal of Library Administration 48.1 (2008): 107-119. Web. 15 November 2011.

Morris, Vanessa Irvin. Readers’ Advisory Guide to Street Literature. Chicago: American Library Association. 2012. Print.

[End Page 19]

Moyer, Jessica. Research-Based Readers’ Advisory. Chicago: American Library Association. 2008. Print.

“Native American.” RT Book Reviews. 2001. Web. 2 February 2014.

Osborne, Gwendolyn. “Romance: How Black Romance—Novels, That is—Came to be.” Black Issues Book Review 4.1 (2003): 50. Web. 10 April 2014.

Pawlowski, Amy. “E-books in the Public Library.” No Shelf Required: E-books in Libraries. Ed. Sue Polanka. Chicago: American Library Association, 55-74. 2010. Print.

Platt, Christopher. “Popular E-Content at the New York Public Library: Successes and Challenges.” Publishing Research Quarterly 27.3 (2011): 247-53. Web. 15 November 2013.

Radway, Janice. Reading the Romance: Women, Patriarchy, and Popular Literature. 1984. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1991. Print.

Rainie, Lee, Kathryn Zickuhr, Kristen Purcell, Mary Madden and Joanna Brenner. “The Rise of E-reading.” Pew Internet & American Life Project (PEW). 4 April 2012. Web. 12 December 2013.

Rainie, Lee and Maeve Duggan. “E-book Reading Jumps: Print Book Reading Declines.” Pew Internet & American Life Project (PEW). 27 December 2012. Web. 11 February 2013.

Ramsdell, Kristin. Romance Fiction: A Guide to the Genre. Englewood: Libraries Unlimited, 1999. Print.

Reid, Calvin. “Kimani Press Offers Fantasy Fulfillment.” PW: Publishers Weekly 257.8 (2010): 8-10. Web. 7 April 2014.

—. “OverDrive Study on How Readers Use Libraries to Find Books.” PW: Publishers Weekly. 18 April 2012. Web. 15 April 2014.

“Romance.” Merriam-Webster: An Encyclopedia Britannica Company. n.d. Web. 15 April 2014.

“Romance.” RT Book Reviews 2009-2015. Web. 9 July 2015.

“Romance Genre: Romance Novels and Their Authors.” RWA: Romance Writers of America. n.d. Web. 14 April 2014.

“Romance Genre: The Romance Reader Statistics.” RWA: Romance Writers of America. n.d. Web. 14 April 2014.

“Romance Sub-Genre: African-American.” RomanceWiki. 26 November 2011. Web. 6 February 2014.

“Romance Sub-Genre: Chica Lit.” RomanceWiki. 2 November 2007. Web 10 April 2014.

“Romance Sub-Genre: Cuban-American Authors.” RomanceWiki. 2 November 2007. Web. 6 February 2014.

“Romance Sub-Genre: Interracial Romance.” RomanceWiki. 11 September 2007. Web. 11 April 2014.

“Romance Sub-Genre: Latina.” RomanceWiki. 2 November 2007. Web. 11 April 2014.

“Romance Sub-Genre: Latina Lit.” RomanceWiki. 30 July 2008. Web. 6 February 2014.

“Romance Sub-Genre: Multi-Cultural Publishers.” RomanceWiki. 2 November 2007. Web. 24 November 2013.

Rosen, Judith. “Love Is All Around You.” PW: Publishers Weekly 246.45 (1999): 37. Web. 7 April 2014.

Schwartz, Meridith. “OverDrive Data Shows Majority Still Like to Browse the Virtual Shelves.” Library Journal. 17 April 2012. Web. 8 November 2013.

[End Page 20]

Simpson, Donna Lee. “RomanceWiki: About.” RomanceWiki. n.d. Web. 24 April 2014.

Stake, Robert. “Case Studies.” Handbook of Qualitative Research. Ed. David O’Brien. California: SAGE Publications, 1994. 236-247. Print.

Stake, Robert E. The Art of Case Study Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1995. Print.

Van Fleet, Connie. “Popular Fiction Collections in Academic and Public Libraries.” The Acquisitions Librarian 15.29 (2003): 63-85. Web. 10 December 2013.

Van Riel, Rachel, Olive Fowler and Anne Downes. The Reader-friendly Library Service. Newcastle: The Society of Chief Librarians, 2008. Print.

Veros, Vassiliki. “Scholarship-In-Practice: The Romance Reader and the Public Library.” The Australian Library Journal 61.4 (2012): 298-306. Web. 10 December 2013.

Wendell, Sarah. Everything I Know About Love I Learned from Romance Novels. Naperville: Sourcebooks, 2011. Print.

White, Ann Yvonne. Genesis Press: Cultural Representation and the Production of African American Romance Novels. Diss. University of Iowa, 2008. Ann Arbor: UMI, 2008. Web. 8 April 2014.

“Wisconsin Digital Book Center FAQ.” Wisconsin Public Library Consortium (WPLC). 16 February 2012. Web. 26 April 2014.

Wisconsin Public Library Legislation and Funding Task Force. “Issue Paper #16: Statewide Access to Electronic Resources.” Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction. 15 August. Web. 10 April 2014.

Wisconsin Statutes 43.00(a-b). “Legislative Findings and Declarations of Policy.” Wisconsin State Legislature. 1985. Web. 10 April 2014.

Wisconsin Statutes 43.24(f-m). “State Aid.” Wisconsin State Legislature. 1997. Web. 10 April 2014.

Wolfram, Dietmar. Applied Informetrics for Information Retrieval Research. Westport: Libraries Unlimited, 2003. Print.

Xie, Iris. Interactive Information Retrieval in Digital Environments. Hershey: IGI Publishing, 2008. Print.

Zickuhr, Kathryn, Lee Rainie and Kristen Purcell. “Libraries Services in the Digital Age.” Pew Internet & American Life Project (PEW). 22 January 2013. Web. 12 December 2013.

Zickuhr, Kathryn, Lee Rainie, Kristen Purcell and Joanna Brenner. “Libraries, Patrons and E-books.” Pew Internet & American Life Project (PEW). 22 June 2012. Web. 13 November 2013.

[End Page 21]