Authors of romance fiction create vast economic capital but this does not necessarily lead to cultural capital. Libraries are collectors and endorsers of cultural capital evident through the selection of materials for library collections and the creation of metadata and metatexts to connect the cultural product to their user. [End Page 1]

In this article, I will be focusing on print/physical book collections and I will discuss how the practice of applying a generic “Romance” or “Mills & Boon” as the catalogue title for books on paperback display stands in libraries creates an absence of metadata which in turn prevents the interplay between cultural capital and economic capital. I explore this interplay by examining Australian cultural institutions, the readers’ advisory process and the way paratext and metadata are used as tools in cataloguing processes so as to facilitate the reader.

Matching a reader to a book is recognised as a core practice of public library work. In library practice this is referred to as readers’ advisory. “Every book has its reader” (Ranganathan 75) is the idea at the heart of Readers’ Advisory services which are user-centered. Joyce Saricks defines readers’ advisory as “patron-oriented library service for adult fiction readers. A successful readers’ advisory service is one in which knowledgeable, nonjudgmental staff help fiction readers with their reading needs” (Saricks and ebrary 2005, 1). Readers’ advisory staff work directly with their readers in delivering reading suggestions but also in developing programs and marketing collateral such as booklist pamphlets, shelf recommendations, posters and displays as well as taking part in staff training in understanding current reading trends, genre studies and service delivery. Amongst the various tools that readers’ advisory staff use to deliver services to readers, the library catalogue allows librarians to access the fiction that will deliver a satisfying service to the reader requesting assistance with their seeking of reading material. The catalogue, more so than any other reading aggregation tool, connects the user with the loan item that is held within the collection. If a book does not have a record in the catalogue, it is placed outside the resources that readers’ advisors can use. E-books remain outside of the scope of this paper as this is not a practice that extends to digital collections.

Conceptual Framework

Bourdieu explores the interrelationship between social, economic and cultural capital within fields and explores them in relation to the influence of power (Bourdieu 126). Cultural capital can be objectified, embodied and institutional. Objectified cultural capital is found in cultural objects and goods such as art, music and literature. Embodied cultural capital is knowledge, tastes and dispositions that are acquired through experiences in the context of home and family, work, community and society. Institutional capital is the capital that is recognised through official structures such as educational institutions. The bestowing of meaning on cultural objects is embodied through cultural capital—that is, the cultural capital that is created and promoted through educational and cultural institutions. Librarians engage in the creation of cultural capital through their practices of selection, cataloguing and promotion of texts deemed suitable for library collections. The authors of romance fiction create economic capital through the sales of their books. It is well documented that sales of romance fiction surpass all other fiction genres (Romance Writers of America; Ramsdell 2012, 15).

Bourdieu writes about the interdependency between the capitals: economic capital should lead to cultural capital and cultural capital to economic capital, but they are not fixed, rather they shift and are influenced by one another (Bourdieu 80). For example, “literary” fiction is bestowed cultural capital through institutions, such as the review [End Page 2] process and library collections, thus leading to economic capital. Romance fiction creates vast amounts of economic capital as it is commercially successful, yet it lacks cultural capital evidenced through the lack of literary reviews, social criticism and lack of collection (Curthoys and Docker 35; Flesch 12; Selinger 308; Ramsdell 1994, 64). Libraries are cultural intermediaries and library use “is accepted as a sign of cultural participation and an indicator of cultural capital, suggesting that libraries can be regarded as sites for the production, dissemination and appropriation of cultural capital” (Goulding 236). Libraries have various roles in society and are institutions of cultural capital. I will explore how cultural, social and economic capital co-exists and intersects in relation to libraries and romance fiction.

Romance fiction and libraries

Despite the significance of romance fiction in contemporary culture, as evidenced by sales figures that make it the most popular of all genres, writers and readers alike are routinely marginalized (Flesch 109; Brackett 347; Vivanco 114). This extends to public libraries, with incomplete catalogue records and unplanned acquisition practices.

In this paper, romance fiction refers specifically to category romance fiction defined as “works of the Mills & Boon type” (Vivanco 11). Juliet Flesch in From Australia with Love also limits her research to the books referred to as category fiction, that is, books published under a series imprint. In Australia, this has predominately been Mills & Boon. She states that “[a] problem with the study of Australian popular romance, even if one excludes from consideration – as I have done – historical romances and longer contemporary novels, is the sheer volume of material for study” (Flesch 43).

Romance novels have yet to receive critical acceptance, which perhaps will be the benchmark for gaining legitimacy from cultural institutions. There have been positive changes in the perception of the romance reader and the literary appeal of romance writing, as well as the emergence of dedicated librarians who develop romance readers’ advisory tools and guides to reading, programs, selection guides and scholarship, through to the establishment of romance fiction review sections in library trade publications (Ramsdell 2012; Adkins et al.; Charles and Linz; Mosley, Charles, and Havir; Ramsdell 1994).

In libraries, as Kristin Ramsdell has noted,

Romances tend to be haphazardly acquired (often through gifts), minimally catalogued and processed (if at all), randomly tossed onto revolving paperback racks, and weeded without thought of replacement when they fall apart (2012, 34).

This suggests that these books are not considered to possess cultural capital. Other examples of this bias abound. For example, in 2012 on the blog of Library Journal, a leading industry publication in the US, the blog’s Annoyed Librarian commented about readers, stating, “it’s also hard to feel sorry for customers who were duped into buying a ‘bad’ romance novel by a good review. After all, they’re all bad books. It’s not like people are reading romances for their literary quality” (Annoyed Librarian). To be clear, there was [End Page 3] substantial backlash from practitioners in the comments on this blog post, but the authority remains with the industry-endorsed blogger. The National Library of Australia’s blog post regarding their Mills & Boon legal deposit collection is headed with “Who’d have thought: Mills & Boon at the National Library,” carrying a tone of incredulity rather than a tone of “here is an interesting collection” that other special collections are afforded in their description on the Behind the Scenes blog (Maguire). Richard Maker, in discussing the genrefication of library spaces and the reader-centred approach, states that,

Most readers who like literary fiction are not primarily concerned with genre. They tend to be more eclectic in their tastes, therefore, the first category, ‘Literary Fiction’, overrides the second [Science-Fiction]. (In terms of the selection of books by the reader the converse is also largely true. By definition the patron who prefers only Romance novels usually has a narrower reading range) (175).

In libraries, cultural capital is recognized through practices such as cataloguing and collection development. Cataloguing involves the description of a book or other item by its author and title and can include the assigning of subject headings. In Bourdieu’s terms (471) these practices have become “doxa”. In other words, they are unquestioned and acceptable practices within the field of librarianship. Joyce Saricks identifies and discusses this library practice for paperbacks that are not catalogued other than with an accession date and barcode item. She states:

Why would you have a collection that you have no access to? The cost of adding them to the database must be far less than the staff time spent trying to find them, day after day, for patrons. Looking for uncatalogued material, which may or may not be on the shelf, is exceedingly frustrating for both staff and patrons and the collection becomes less useful. Unfortunately, many administrators fail to calculate this on-going staff time when they decide not to put items in the database (Saricks 422).

Paperback romance fiction in the past was commonly added to library collections only through donations (Flesch 59), not through a thoughtful, deliberated selection process. Though this is no longer the case for all libraries, it is a practice that is still in place. Romance fiction is not afforded full catalogue records through budgetary constraints at the detriment of the library service to the reader yet romance fiction should be afforded the same treatment as other genres (Ramsdell, 2012 37).

Cataloguing and the Interplay between Paratexts and Metadata

To understand the basis of library cataloguing practices and the creation of catalogue records conceptually, it is important to explore the levels of access to a cultural object, in particular, paratext and metadata. Gerard Genette in Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation describes paratext as the material that is at the threshold of the text (2): that is, all the art, acknowledgements, prefaces, covers, advertising, distribution and intertexts [End Page 4] and interviews with the design team (publisher, author, designer) of a text. Genette says that without the paratext the reader cannot access any of the text (Genette and Maclean 261). Paratext has two elements. Epitext are the items that are attached to the actual codex, such as the cover art, blurbs, title, author and publisher information, index and contents pages. Peritext are the collateral that promotes the text, that is, author interviews, marketing and publicity materials. Genette shows how liminal devices and conventions, both within and outside the book, form part of the complex mediation between book, author, publisher, and reader.

A text also has metatextualities: that is, the metatext, which is the data and information that is developed in relation to the text by users outside of the text’s creative team. “All literary critics, for centuries, have been producing metatext without knowing” (Genette xix). Metatext is created by people such as literary critics, cataloguers and reader reviewers. Literary criticism, for example, is metatext; it cannot be controlled by the creators as it is published outside of the paratextual threshold. This is not to say that there is no communication between the paratextual team and the developers of metatext. Publishers send information to national libraries to consult on the Cataloguing-in-Publication (CIP) record and publishers send reviewers and critics copies of their books. CIP is a catalogue record that is created by national library cataloguers who receive title pages, author names, blurbs and a synopsis of the book sent by the publishing team (Intner and Weihs 5). Often, the metatext can be hard to disregard as it carries authority (Genette 339). Literary critics, reader reviews and fanfiction are all part of a novel’s metatexts as is a library catalogue record which is a book’s metadata (Van der Veer Martens 582). Metadata is structured data that supports the function of its object or text (Greenberg 1876).

Here, the concern is with the creation of a cataloguing record as metatext. Professionals in roles such as cataloguers and database administrators make high-level decisions on the information that is made available for both the end users (readers) and the intermediary (librarian), helping the reader access the text. Books have their subject headings decided upon by third parties (cataloguers), unlike metadata that is generated by the creator, for example, fanfiction whereby the creator tags their work with subject headings that are either preset or of their choice (Lawrence and schraefel 1746). Metadata is an instrumental part of a reader and a librarian accessing the items that are available in a library. This structured data acts as a resource description and discovery tool. Institutions use international standards, such as MARC/RDA records in catalogues, which subsequently are used in readers’ advisory and reference searches. Paling, in Thresholds of Access: Paratextuality and Classification, describes the cataloguing process as belonging to the paratext. Librarians, and more precisely, cataloguers, are not part of the creative process. Instead they are third parties in the selection of descriptors to be assigned to a book (Paling 134). In this process, they create access to the cultural object, thus enhancing its cultural capital.

Cataloguers are professional metadata creators because they make “sophisticated interpretative metadata-related decisions” so as to classify and give value laden attributions to content created by other individuals (Greenberg 1882). Raymond Williams in his discussion of culture notes that, “we need to consider every attachment, every value, with our whole attention; for we do not know the future, we can never be certain of what may enrich it” (363). This is particularly true for cataloguers who are creating the attachments that bring the reader to the text. The guiding ideology for cataloguing since the [End Page 5] late nineteenth century has been based on Cutter’s principle of user convenience in which “the convenience of the user must be put before the ease of the cataloguer” (Caplan and ebrary 54). Cataloguers are attributed with the ability to decide upon interests and values that need to be attached to a text they have received, whether through legal deposit requirements or through the CIP scheme available to authors and publishers pre-publication (Chapman 114). Third-party metadata is also created for items that have been selected for a library collection through outsourcing, for example, by library suppliers and not by the library staff themselves—though they would have been responsible for giving cataloguing instructions to the supplier (Edmonds 125). This metadata needs to be enriched so as to enable other library service provisions, particularly in reference and readers’ advisory services. The cataloguing decisions of a public library, whether it is in a local council, district, county or shire, differ greatly from the role of a cataloguer in a national or state library, which may indeed have a more open line of communication with a book’s creative team due to the CIP process (Genette 32; Paling 140). Using CIP data, cataloguers select suitable subject headings that are then sent back to the publisher for inclusion in the books’ paratext, i.e. on the verso of the title page. Occasionally, a publisher may request for a change of subject headings but this depends on the awareness of the author and/or publishing team in how these subject headings are created (Intner and Weihs 6).

Catalogue records exist on national bibliographic databases for published books due to a number of accepted practices between publishers and national libraries including CIP, legal deposit requirements and International Standard Book Number requests which assign a unique number to books. This core level metadata is made available for public and local libraries to download through copy cataloguing practices and for readers to search, either through their own national libraries or through World Cat—a collaborative database allowing a federated search of subscribing libraries and booksellers across the world through the one portal. Many libraries rely heavily on copy cataloguing and preexisting catalogue records can be obtained and local modifications can then be made to the record (Caplan and ebrary 57).

The catalogue record not only contributes to the creation of cultural capital: in Australia it contributes to the development of economic capital. The metadata entered into a local library management system is not only utilised for connecting a reader to a text and for staff to create resource lists, displays and programs using the materials that are held by the library, but, just as importantly, it is used as a system for administering and managing resources including copyright, digitisation schemes and payment schemes such as the public lending right. The Australian Ministry for the Arts describes Public Lending Rights (and Educational Lending Rights) as:

Cultural programs which make payments to eligible Australian creators and publishers in recognition that income is lost through the free multiple use of their books in public and educational lending libraries. PLR and ELR also support the enrichment of Australian culture by encouraging the growth and development of Australian writing (Public Lending Right Committee).

Public Lending Right is a program with which authors receive economic capital on the basis of having received endorsement by cultural institutions. That endorsement comes from the [End Page 6] cataloguing record and the record of borrowings of that item. Thus, it can be seen that it is not just the cultural object itself which is part of the interplay between cultural and economic capitals. As Pecoskie states, although the book itself is central to what she calls “the informational sphere”, following Genette and Bourdieu, it is other elements including the cataloguing record that create the links between writers and “cultural agents (including libraries)” and consequently between the cultural and the economic (Pecoskie and Desrochers 232).

It is the metadata connected to books that is instrumental in connecting authors to cultural capital and, by extension, institutionalised economic capital. The catalogue record is the form of metadata that allows readers’ advisors to promote and endorse the text that is waiting to be discovered. In the absence of any catalogue record, the text cannot be discovered. But that text cannot be discovered if the metadata does not exist. Paratextual conventions serve a functional and informational purpose as they are the access point for information (Pecoskie and Desrochers 232). Readers’ advisory services are already making some use of other aspects of the paratext in order to bring together titles that have similar characteristics (Pecoskie and Desrochers 236). These are reader appeal factors (Saricks and ebrary 2009, 40) that connect works across genres. Pecoskie writes, “Libraries can capitalize on the documented information regarding award nominations and prizes won […] in order to bring together titles that may have similar characteristics – or, to speak in cultural terms, have been deemed worthy by the application of similar criteria” (236). If there is no cataloguing record for romance fiction, there is no starting point for adding other elements of paratext, such as award status or best seller listings. If libraries do not produce metadata for romance fiction, books cannot be found as the result of a catalogue search, and they remain invisible to the readers’ advisory team and to readers. Thus, they cannot be recommended to readers and within the cultural institution of the library, their cultural capital does not increase through borrowing. And even if the books are borrowed, the lack of cataloguing records means that the borrowing of the particular book is not recorded. The loan is recorded only as a generic item. This in turn, through Public Lending Right, affects the creation of economic capital, because there is no evidence on which to base payments to these authors whose works are held in the public library.

Evidence of practice

Cataloguing records are used as the basis for recording loans of books. As already noted, in some Australian public libraries, paperbacks are often not catalogued with a full author and title entry. Instead, a record is given a generic title such “General Paperbacks” and then an accession number is given for each item that is attached to this record. This practice, which is not found in every public library, has grown out of the resistance to paperbacks since their introduction to library collections (Mosher 3). Paperbacks were seen as quick reads, disposable and many libraries chose to keep them physically separated from their hardback fiction collections as well as giving them base level accessioning.

This practice, then, identifies each book only by a number. It is no longer seen as having been created by an author; the book becomes detached from its creator. It is also detached from its title. By removing not only the author but the title and all other paratextual and metatextual elements that connect the book with its potential readers, [End Page 7] both the author and the reader cease to exist (Barthes 55). Romance fiction is a genre where name recognition is very important (Proctor 16) as readers often read an author’s oeuvre rather than a single title. In the library context, an author has to be acknowledged as it is often the most authoritative and effective way of accessing their body of work. In creative practice, Australian authors of romance fiction are aware that this practice is impacting their visibility (Veros 302).

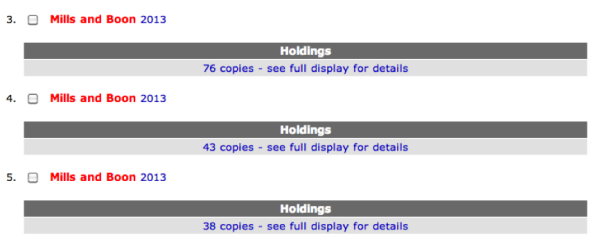

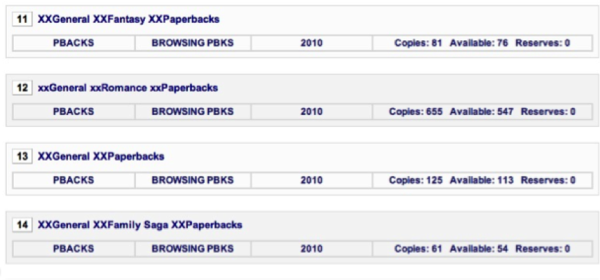

Evidenced below are library catalogue records which show this practice. Each title has listed the number of copies attached:

A detailed display of the items in this record shows only the collection, shelf number and availability status of the copies:

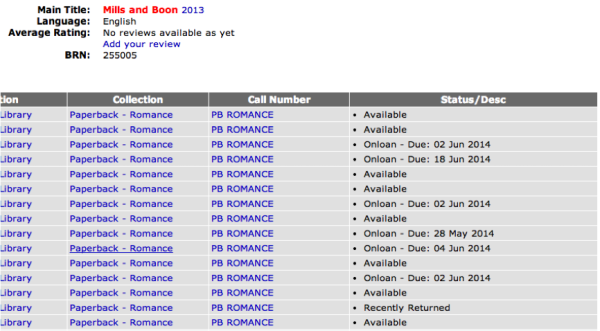

[End Page 8] This practice is not confined simply to romance fiction, but to other paperbacks such as thrillers, westerns and Science Fiction as well, as the following example shows:

These collections are rendered even more unsearchable through the use of unnatural language for their titles. xxGeneral, xxRomance, xxPaperbacks are terms that readers will not search for when they are accessing the library catalogue.

This practice, however, sometimes leads to unexpected consequences. Public library collection management systems are being updated to include features which promote the most popular items in the library catalogue. A letter received recently shows how the practices which were intended to show that an item was not deemed an integral part of a library collection actually led unintentionally to the creation of cultural capital in a different way.

When we installed a new LMS in 2010 it had a few new features that we didn’t have in our old system. Most obvious was the box on the main catalogue search screen called ‘What are others are reading’ this box displayed the Hottest Title, Hottest Author and Hottest Subject as a teaser for readers. It wasn’t long before our library’s hottest title was established – Mills & Boon. It made the list and stayed there for months. This upset certain staff, including our manager, as they would have preferred to see ‘real’ books listed (personal communication).

The letter went on to explain that the IT team discovered that the one title kept showing up as there were large numbers of items attached to the one record.

Since they weren’t ‘real’ books that also meant they didn’t need a title, author or ISBN – just a barcode. Every single Mills & Boon we received was added to that single record – for decades. You could borrow them but you certainly couldn’t search for them as we had no idea what titles we actually had. And [End Page 9] borrow them people did – Mills & Boon books are one of our highest turnover items and as they all linked to the same record it was a clear winner in terms of loans (personal communication).

The concern of the manager and other staff was that they didn’t want their library web page to show that “Mills & Boon” was their highest loaned item as they wanted a variety of titles showing up on the “Hottest Title” lists.

The issue was finally resolved by ‘blocking’ that record from the display list so ‘real’ book titles could be displayed. There was (and still is) great resistance to actually cataloguing individual Mills & Boon titles (personal communication).

This example shows clearly that library practices are intended to minimise opportunities for the creation of cultural capital from category romance fiction. The consequent impact on economic capital for the authors does not seem to have been considered.

Conclusion and implications

This paper has shown that the cataloguing practices in some Australian public libraries do hinder the interplay between cultural capital and economic capital. The impacts of cataloguing practices, which may in the first instance appear to be a cost-saving measure within the library, can be costly in terms of lack of service provision to the reader. Further, the practices can diminish the case that public libraries can make for the use of the services they provide. Circulation figures are often used as a justification for funding from their parent organisations and similar to the retail success of romance fiction, collections of paperback category romance fiction are highly borrowed and highly used. Yet the books which do not merit even a partial author/title entry into a library catalogue remain invisible to anyone other than the physical user who accesses collections by being physically present in the library and discovering their reading choices through browsing. This may have been suitable in the twentieth century when the only access to collections was to physically visit the library but library catalogues have for many years been accessible through the internet. People make their reading choices from browsing the catalogue thus necessitating the Library of Congress to expand subject headings to allow for fiction titles (Saricks and ebrary 2005, 8).

As Intner and Weihs indicate, when a library makes a decision to diverge from standard practices, “no visit from the Catalog Police to the agency will ensue” (Intner and Weihs 11). However, changes to cataloguing practices are not impossible. These practices tend to be formulated through a mixture of “peer pressure, institutional culture and what is acceptable within that institutional culture” (Adkins et al. 65). While peer pressure is slowly bringing about change, it is still the case that the very common form of catalogue entry, which is one record with many attached items, lacks meaningful metadata. Thus it is that category romance is rendered unsearchable through the library catalogue. Non-existent metadata leaves no cultural imprint in institutional collections for scholars and archivists and the public to reflect on the presence of romance fiction in Australian society. [End Page 10] Cataloguing of literary fiction, which sells less than a third of that of romance, is comprehensive, yet romance fiction is not catalogued to the same level (Veros 301). This has consequences for systems of institutional payments such as Public Lending Rights: books that remain uncatalogued results in libraries inadvertently withhold payment from eligible authors. In other words, these items do not generate the economic capital which is due to their authors. Aside from any economic impact, romance fiction authors whose books receive this treatment do not receive institutional recognition from libraries for their institutional role as publishers in creating this cultural capital.

“[A] group’s presence or absence in the official classification depends on its capacity to get itself recognized, to get itself noticed and admitted, and so to win a place in the social order” (Bourdieu 483). To a large extent, the readers and writers of category romance fiction do not yet have a place in the social order mediated through the library. This finding has implications for practice and suggests the need for further research. From a practice perspective, the lack of recorded metadata for certain types of cultural objects in a public library borders on censorship. The lack of cataloguing record leads to those cultural objects becoming invisible within the constraints of the institution. This in turn can be seen as a form of censorship, because readers’ advisors are unable to meet the reading needs of certain readers and the readers themselves use alternative places to find the reading they enjoy, for in their use of the catalogue, the books they would like to read are hidden from them. Further, the lack of metadata for paperbacks in general raises questions about the way that metadata may be assigned to the same cultural objects now available in electronic form as e-books.

This analysis of the role of cataloguing records in the interplay between cultural capital and economic capital has shown that there is a need for further research, at least in two areas. The first is the significance for metadata and paratext in the creation of cultural capital in other forms of popular fiction, including user-generated content such as fan fiction. The second is the importance in economic and cultural terms of the inadvertent withholding of Public Lending Right payments to authors of category romance and other categories of cultural objects which are not given full metadata records in public libraries. [End Page 11]

Works Cited

Adkins, Denice, Linda Esser, Diana Velasquez and Heather L. Hill. “Romance Novels in American Public Libraries: A Study of Collection Development Practices.” Library Collections, Acquisitions, and Technical Services 32.2 (2008): 59-67. Print.

Annoyed Librarian. “Rage, Rage Against the Amazon Reviewers.” Library Journal. 27 December 2012. Web. 20 Apr. 2014.

Anonymous librarian. Letter to the author. 29 April 2014. Email.

Barthes, Roland. “The Death of the Author.” The Rustle of Language. Trans. Richard Howard. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1986. 49-55. Print.

Bourdieu, Pierre. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1984. Print.

Brackett, Kim Pettigrew. “Facework Strategies among Romance Fiction Readers.” Social Science Journal 37.3 (2000): 347-360. Print.

Caplan, Priscilla, and ebrary. Metadata Fundamentals for all Librarians. Chicago: American Library Association, 2003. Print.

Chapman, Ann. “Bibliographic Record Provision in the UK.” Library Management 18.3 (1997): 112-123. Print.

Charles, John, and Cathie Linz. “Romancing Your Readers: How Public Libraries can Become More Romance-Reader Friendly.” Public Libraries 44.1 (2005): 43-48. Print.

Curthoys, Ann, and John Docker. “Popular Romance in the Postmodern Age. And an Unknown Australian Author.” Continuum: Journal of Media & Cultural Studies 4.1 (1990): 22-36. Print.

Edmonds, Diana. “Outsourcing in Public Libraries: Placing Collection Management in the Hands of a Stranger?” Collection Development in the Digital Age. Eds. Margaret Fieldhouse and Audrey Marshall. London: Facet, 2012. 125-136. Print.

Flesch, Juliet. From Australia with Love: A History of Modern Australian Popular Romance Novels. Fremantle, WA: Fremantle Arts Center Press, 2004. Print.

Genette, Gérard, and Marie Maclean. “Introduction to the Paratext.” New Literary History 22.2 (1991): 261-272. Print.

Genette, Gérard. Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1997. Print.

Goulding, Anne. “Libraries and Cultural Capital.” Journal of Librarianship and Information Science 40.4 (2008): 235-237. Print.

Greenberg, Jane. “Metadata and the World Wide Web.” Encyclopedia of Library and Information Science 3 (2003): 1876-1888. Print.

Intner, Sheila S., and Weihs, Jean Riddle. Standard Cataloging for School and Public Libraries. 4th edition. Westport, CT: Libraries Unlimited, 2007. Print.

Lawrence, K. F., and schraefel, m. c. “Freedom and Restraint Tags, Vocabularies and Ontologies.” Information and Communication Technologies (2006): 1745-1750. Print.

Maguire, John. “Who’d have Thought? Mills & Boon at the National Library.” National Library of Australia. 29 August 2011. Web. 20 September. 2013.

Maker, Richard. “Finding what You’re Looking for: A Reader-Centred Approach to the Classification of Adult Fiction in Public Libraries.” The Australian Library Journal 57.2 (2008): 169-177. Print.

[End Page 12]

Mosher, Fredric John, ed. Freedom of Book Selection: Proceedings of the Second Conference on Intellectual Freedom, Whittier, California, June 20-21 1953. Chicago: American Library Association, 1954. Print.

Mosley, Shelley, John Charles, and Julie Havir. “The Librarian as Effete Snob: Why Romance?” Wilson Library Bulletin 69 (1995): 24-25. Print.

Paling, Stephen. “Thresholds of Access: Paratextuality and Classification.” Journal of Education for Library and Information Science 43.2 (2002): 134-143. Print.

Pecoskie, Jen JL, and Nadine Desrochers. “Hiding in Plain Sight: Paratextual Utterances as Tools for Information-Related Research and Practice.” Library & Information Science Research 35.3 (2013): 232-240. Print.

Proctor, Candice. “The Romance Genre Blues Or Why we Don’t Get no Respect.” Empowerment versus Oppression: Twenty First Century Views of Popular Romance Novels. Ed. Sally Goade. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Press, 2007. 12-19. Print.

Public Lending Right Committee. Public Lending Right Committee Annual Report 2010-2011. Canberra: Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, 2011. Print.

Ramsdell, Kristin. “Book Reviews: Romance.” Library Journal 119.9 (1994): 64-67. Print.

—. Romance Fiction: A Guide to the Genre. 2nd edition. Santa Barbara, CA: Libraries Unlimited, 2012. Print.

Ranganathan, Shiyali Ramamrita. The Five Laws of Library Science. Madras: Madras Library Association, 1931. Print.

Romance Writers of America. “Romance Literature Statistics: Industry Statistics.” n.d. Web. 28 Jul. 2012.

Saricks, Joyce G. “Providing the Fiction Your Patrons Want: Managing Fiction in a Medium-Sized Public Library.” The Acquisitions Librarian 10.19 (1998): 11-28. Print.

Saricks, Joyce G., and ebrary. The Readers’ Advisory Guide to Genre Fiction. 2nd edition. Chicago: American Library Association, 2009. Print.

—. Readers’ Advisory Service in the Public Library. 3rd edition. Chicago: American Library Association, 2005. Print.

Selinger, Eric Murphy. “Rereading the Romance.” Contemporary Literature 48.2 (2007): 307-324. Print.

Van der Veer Martens, Betsy. “Approaching the Anti-Collection.” Library Trends 59.4 (2011): 568-587. Print.

Veros, Vassiliki. “Scholarship-in-Practice: The Romance Reader and the Public Library.” The Australian Library Journal 61.4 (2012): 298-306. Print.

Vivanco, Laura. For Love and Money: The Literary Art of the Harlequin Mills & Boon Romance. Penrith, Cumbria: Humanities-Ebooks, 2011. Print.

Williams, Raymond. Culture and Society, 1780-1950. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin, 1961. Print.

[End Page 13]