An Alluring Beauty

The Nellie Stewart bangle was a plain gold bangle worn by many Australian and New Zealand women in the early twentieth century as a sign of romantic attachment. Before recovering the Nellie Stewart bangle as an important addition to the history of colonial fashion and sentimental object, it is important to understand the charismatic [End Page 1] appeal of Stewart’s celebrity, the social mores of the time and how they overshadowed her private life, thus obscuring the real circumstances of the original bangle’s existence. Actress, singer and humanitarian, and once a household name in Australia and New Zealand, Nellie Stewart was a great beauty and a fashion icon whose style was widely emulated. Born Eleanor Stewart Towzey, in Sydney in 1858 to a theatrical family, she held her adoring public for over fifty years, until her death in 1931. She was called “Australia’s Idol” by press and public alike, and was their most loved star (Cooper 1931: 9). She also unwittingly began a fashion trend in the form of a ubiquitous bangle. Similar bangles are still worn, but commonly, they are known as golf bangles and very few know their history in Australia. Contemporary jewellers and wearers, have seldom heard of Stewart. Even if they do know such pieces as versions of the ‘Nellie Stewart bangle’ few will be aware of the star it was named after, let alone the story of the origin of its once famous namesake. (Fig. 1)

(property of the author)

All of the bangles were based on Stewart’s own bangle, which she wore for forty-six years, never once removing it. It was so conspicuous in her stage presence, in her personal life and in representations of her that it became the basis of a fashion trend. For Nellie Stewart, however, the original bangle was never about fashion. It came into being in 1885 when her lover, George Musgrove, gave her twenty-five gold sovereigns and his own design [End Page 2] for the bangle. What I am interested in here is how the romantic stories of Stewart’s own bangle and the bangles it inspired become inter-implicated in private and public life for women in the Australia and New Zealand of Stewart’s lifetime. For decade after decade these bangles were exchanged as material symbols of romantic love in courtship rituals and handed down through generations as sentimental love objects, without the participants’ knowledge of the signification of the original bangle as a tangible sign of devotion for that first couple.

Known for her ageless looks, at the age of thirty Stewart was amongst twenty-five theatrical women included in what must surely be one of Australia’s first fan magazines, containing black and white portraits and profiles of each actress. The self-published Pets of the Public: A Book of Beauty (Ellis 1888) is an early example of the kind of celebrity title that assumes ownership of famous people by their publics. This was a cultural trend that would later be crucial in the promotion of the Nellie Stewart name and the bangles that became associated with it. “Actresses were of great interest, given their supposedly questionable morals as well as their stylish dress, jewellery and hairstyles. Many were, of course, ‘protected’ by rich, prominent men, and some made advantageous marriages” (Church Gibson 2012: 42). These aspects will be investigated through close attention to the way Stewart’s celebrity was marketed along with her iconic bangle. There is no salacious press regarding Nellie Stewart, indeed to the contrary. Her good moral character seems to have been an integral part of her reputation, despite an annulled marriage, her being a single mother, and living the rest of her life with a still-married man. This man, George Musgrove, was very much (at times) a rich, prominent and influential man, and very well could have ‘protected’ her good name. It is something, however, that remains ambiguous and can only remain as speculation.

Nellie Stewart worked mostly within light opera, pantomime and other forms of popular entertainment, and in contrast to Nellie Melba, she made only one sound recording shortly before she died. Even though she had success abroad, she spent most of her performing life amongst the Australian and New Zealand people. Embraced as “Australia’s darling” and the “Rose of Australia” she was a deeply loved popular cultural figure. Paradoxically, it may be for this very reason – that she was a popular rather than high cultural figure – that despite her longevity, once her loving audiences disappeared, so also, to a significant extent, did cultural memory of her.

However, during her career, Stewart was well aware of the nature of her popular appeal, revealing in her autobiography an astute recognition that it involved more than her beauty and performance skills: “I am thankful for that magnetism in me, that powerful, elusive not-easy-to-suggest something which has made all my successes intimately personal” (Stewart 1923: 3). That is, Nellie Stewart grasped that the strength of the bonds between popular entertainers and their publics is frequently more than might be assumed when the attention is on “idols” or even ‘pets”. It can involve something “intimately personal” that fans come to experience as a relationship, albeit unrequited, between each of them and the unattainable “star”:

She was Sydney’s sweetheart, and of course mine too, (but I wasn’t hers). Just a fascinated youth of 16 in 1891, many nights I stood on a stone and wood-blocked street in front of the Lyceum and watched Our Nell … (Frederick Nyman in Skill, 1973: 52) [End Page 3]

Australia-wide, her name became synonymous with beauty and style. Reportage after her appearance at the Melbourne Cup demonstrates Stewart’s celebrity allure:

Nellie Stewart, Idol of the Melbourne stage, led the Fashion Stakes – and Melbourne followed. In 1901 the ‘Nellie Stewart’ line was the vogue. (Bernstein in Skill, 1973: 67)

From the moment of Stewart’s propulsion into the spotlight she was identified by an ever-present gold bangle. Copies of her bangle became sought-after fashion pieces and then became a “craze”, notably through no action of hers or her associates in relation to the production of the copies or the naming of them as “Nellie Stewart bangles”. The wide manufacture and popularity of the Nellie Stewart bangle was simply an effect of her much-beloved status. Her name became ‘attached to’ the adornment, understood as a public form of flattery in the construction of her fame.

Michael Madow extensively explores this practice of the commodification of famous personas and publicity rights, tracing historical changes in the status of celebrities and the emerging commercialisation of their names, images and identities. He explains that

[L]arge-scale commercial exploitation of famous persons goes back at least to the eighteenth century. It continued throughout the nineteenth century as well, all the while engendering little in the way of private complaint of social disapproval. Indeed, the practice seems to have been supported by a widely shared conception of famous persons as a kind of communal property, freely available for commercial as well as cultural exploitation. (Madow 1993: 8)

He notes how there was little control or litigation over this kind of exploitation until the latter part of the nineteenth century. The proliferation of one’s good name on consumable objects was conceived as part of fame’s reward. In the 1880s Sarah Bernhardt, with whom Nellie Stewart was often compared, was also the subject of this kind of merchandising in the form of cigars, perfume, candy and eyeglasses, for example, and like Stewart, Bernhardt did not profit, except in the continued circulation of her name. Oscar Wilde’s name was appropriated to sell freckle powder. Similarly, Nellie Stewart’s image, with closed mouth, appeared on a promotional card for toothpaste.

As with so many objects that are associated with the famous, in the case of Nellie Stewart bangles, the traits of the individual are transferred to the linked artefact: vicariously touched by Stewart’s aura, ladies who adorned themselves with these particular bangles were perceived as part of the fashionable set and doubtless aspired to the allure associated with Stewart herself. Possession of this gold accessory bonded women to their absent idol, as they physically carried an indexical trace of her social standing with them.

“[L]ike stage properties, accessories make meanings under the ever useful trope of synecdoche – the part stands in for the whole … Physical objects like hand props or articles of dress thus make vivid verbal and visual metonyms” (Roach in Engel 2009: 282) [End Page 4]

This in turn, confirms Stewart’s own status as object of what Marcel Mauss calls prestigious imitation (1973: 75). Anthropologically, Mauss’s interest is in parental, religious and other roles of governance or authority, but his ideas are also valuable in relation to cultural trends such as fashion and the association of styles with famous people who are perceived as having desirable traits, which are emulated by others. In tracing the emergence of what has come to be called celebrity culture, Madow notes how

[s]tage actors in particular became objects of popular fascination and widespread emulation, as the nineteenth century’s “culture of character,” which had stressed self-discipline and self-sacrifice, gave way to a culture that emphasized instead the importance of a distinctive “personality.” Traditional social elites responded to this challenge not by closing ranks against theatrical celebrities but by visibly associating with them, hoping thereby to retain some of their former prestige and cultural authority. (Madow 1993: 40)

Stewart straddled both of these spheres, being at once respected for her good deeds and character and also recognised for her stage performances and charismatic personality. Stylish, talented and also noted for her frequent charitable work, Stewart thus became available as a socially appropriate model for imitation, indeed for a kind of worship, as indicated by reference to her as an “Idol”. As Skill also observes, “so potent was the actress’s appeal that thousands of women, then and for years to come, wore a Nellie Stewart bangle …” (Skill 1973: 41)

A Gift of Gold

Gentlemen of the day were of course also enamoured of Stewart, but equally they were aware of her style status and social standing amongst women. Alert to the widespread desire for the Nellie Stewart bangle, they continued the craze in order to court favour:

In Newcastle long ago, years before his election to Parliament, Fred Roels proudly presented one of the circlets to his fiancé. He was following the lead of other young men who aimed to make a fashionable impression. (Skill 1973: 41)

George Musgrove was a theatrical entrepreneur and a member of the J. C. Williamson’s theatre company, or ‘the Firm’. The sovereigns from which the original bangle was made were a reward for the money raised through a benefit concert, held to erect a statue to General George Gordon after his death in the battle for Khartoum. It is inferred in Stewart’s autobiography that these sovereigns formed part of the money that was in excess of the sum raised required to build the statue. If this was true, the ethics of such a deed become questionable. Musgrove could have easily bought any item of jewellery for Stewart with the money, except that one item which would have publicly cemented their loving bond: a wedding ring. Musgrove was estranged from his wife who never would divorce him and Stewart was still legally bound to an unconsummated marriage, which would much later be [End Page 5] annulled.[1] In having the sovereigns made into the gold bangle of Musgrove’s design, Stewart turned the gift of money, which has no sentimental worth, into an object of significant emotional value to both of them. She converted the coins into a body object, which she never removed from her wrist. What had occurred was a change in form, perhaps as important to the couple as the change in the public and private form(s) of their relationship that could have occurred had they been free to marry.

[End Page 6]

The bangle would have been solid, very weighty and made of 22 carat gold (Fig. 2). If they were early sovereigns the gold would have been of a lighter colour “due to the use of silver instead of copper to form an alloy to the prescribed legal standard’ (Duveen & Stride 1962: 95). According to Jonathan Cooper (2005), specialist in Australian colonial jewellery, the sovereigns were also probably mixed with copper in the melt to give the bangle strength. The amount of copper would also have affected the colour of the gold – the more copper, the pinker the hue. This certainly would have been a very valuable item of jewellery: worth the twenty-five coins that went into it plus the manufacturing cost. But to give some idea of value: in the late nineteenth century one gold sovereign would have been about one week’s wages for a common labourer; in 1914, nearly thirty years after the bangle came into existence, the average weekly earnings of a man were £3 per week. If we were to consider its value differently, in terms of an equivalent item today being worth half a year’s modest wages, the bangle would be at least equivalent to $20,000 – $25,000. In terms simply of the value of gold, the original Nellie Stewart bangle, were it still in existence, would be worth approximately $2,500, without taking into consideration any antique value. Given its place in the history of Australian jewellery, the value would, of course, increase astronomically for collectors, while its heritage value as a museum piece, as part of Australian cultural history, would be difficult to assess.

All this monetary, cultural and social value, though, has no bearing on the private value to Nellie Stewart and George Musgrove in terms of their shared lives, which included the birth of their daughter, Nancye in June 1893. The bangle for them was much more than a decoration or memento. It “stood for” a wedding band and was treated as such by Stewart. It was their private recognition of their intimate relationship with each other, publicly worn. However, unlike the circumstances attending a wedding ring, their shared private life and the bangle’s part in it, were not declared publicly until Stewart’s autobiography appeared almost forty years after the bangle first appeared on her wrist.

The bangle’s first stage appearance was in 1886 in Stewart’s premiere role of Yum Yum in The Mikado. Throughout her professional life, because it never left her arm, such an obviously large gold bangle had to be disguised sometimes, such as when she played male characters in pantomime or a poor girl (like Nell Gwynne – a part for which she became most famous). On such occasions, the bangle would be either hidden under long sleeves, or covered with braid. (Fig. 3) [End Page 7]

Stewart’s association with the role of Nell Gwynne would never leave her. The ongoing conflation of the Nell the actress, with Nell, the role is not accidental, but was used as a discursive device in the publicity for Stewart’s own public identity (Lipton 2011). In addition to this, the two shared several life characteristics. Nell Gwynne was famous in the seventeenth century as the poor theatre orange seller, who not only became an actress in restoration comedy, but also Charles II’s mistress who bore him illegitimate children. The play Sweet Nell of Old Drury, is reference to the Theatre Royal at Drury Lane, where Stewart herself would later also famously perform as principal boy in pantomime. Charles II was a patron of the arts, and George Musgrove, although not a king, was a theatrical entrepreneur who would never marry his true love.

Baubles, Bangles and Brides

For Nellie Stewart and George Musgrove the bangle signifying their private relationship was perpetually disguised, merely as a piece of jewellery without such deep personal significance. But wedding bangles have been a common tradition across a range of cultures. Indian wedding customs involve the bride’s receiving bangles (often coloured glass) from her mother-in-law. Both Stewart and Musgrove had travelled to India and quite possibly were aware of this custom. In Victorian England, a bangle was often given to the future bride by her fiancé upon their engagement, with another given on their wedding day (‘Mirabel’ 1909a; 1909c). These bangles were identical and worn in pairs. A variety of designs were used, with safety chains, and they symbolised good luck or faith, hope and charity. [End Page 8]

Such items of jewellery became important cultural artefacts, as items into which memories are embedded. They symbolically share a lifetime of lived experience with their owner-wearers, who are usually women, especially in the case of wedding jewellery. This is why items of personal jewellery are such sought-after objects in family histories, embodying as they do a vicarious transference of those memories to the women who may inherit and so also wear them. Thus, in usual circumstances, the object that signifies the love between a couple takes on a public life not only during the lives of that couple, but across generations, becoming a part of the private and public stories of families and cultures. For Musgrove and Stewart, though, the bangle remained an intensely private gesture.

This makes it all the more extraordinary that the most public and well-known manifestation of popular “love” for Nellie Stewart was a craze for replicas of that gold bangle. Because Stewart never removed her own bangle, it became her public signature and a celebrity object. For Skill (1973: 41) this was an ingenious move on the part of Musgrove: every time a girl placed the bangle on her arm, she thought of Nellie Stewart. “Roach suggests that images of stars with accessories give the spectator a kind of access to the celebrity, a gateway into the aura of illusions surrounding that particular figure” (Engels 2009: 282). Therefore, when a girl first wore her Nellie Stewart bangle we might imagine the kind of heightened response she might have had through the tactility and the resemblance of her own bangle to that of her idol’s. Roach argues that through accessories “ordinary people can experience a spurious but vivid intimacy with the public figures they represent” (Roach in Engels 2009: 282). But as we have seen, the gift held a significance that remained private until 1923. Neither Musgrove nor Stewart had any part in the manufacture or promotion of the bangles. The craze seems to have had a range of origins, including the recognition on the part of jewellers of Stewart’s role as style-setter, as well a women’s desire to wear a bangle like the one constantly worn by Nellie Stewart, and men’s desire to please women.

The gold rushes of the second half of the nineteenth century brought about an abundance of gold, resulting in an influx of gold jewellery.[2] Bracelets became particularly fashionable:

The nineteenth century saw a new vogue for bracelets. As many as four were sometimes worn on each arm, and they continued to be popular when other forms of jewellery were temporarily out of fashion… but by far the most popular bracelet of the 1870s was a plain gold bangle. (Mason 1973: 41, 42)

Although this was true and remains so today, “plain gold bangles” come in many forms. Once the craze was underway, from the second half of the 1880s on, an authentic Nellie Stewart bangle was a completely round ring, usually not oval, and not flat on the inside surface. The bangle’s similarity to a wedding band cannot go unnoticed: it is plain, with no embellishment such as hand chasing, repousse work, engraving, stippling or black taille d’epergne enamelling, as was popular in the late Victorian and Edwardian periods. Nellie Stewart bangles were usually of rose gold, hollow and filled with wax to prevent dings and denting.[3] They could be hinged or unhinged. We know the original was unhinged and different from most bangles of the time, as Stewart (1923: 159) explained in her autobiography: [End Page 9]

It was large and of a new style – it was forced on my arm and has never been removed since. I daren’t think how many other Nellie Stewart bangles, of all qualities, have been made and worn in Australia since then. There was a time when no really smart girl would be without one. A friend tells me he counted over three hundred on women going into a theatre in Sydney one night.

The bangle’s popularity as a coveted fashion item, even as late as the 1920s, is evidenced by studio portraits and many a Box Brownie family photo, at a time when home photography had become more accessible to the average person (Fig. 4).

(by kind permission of Hilda McDonnell, Lower Hutt, NZ)

[End Page 10]

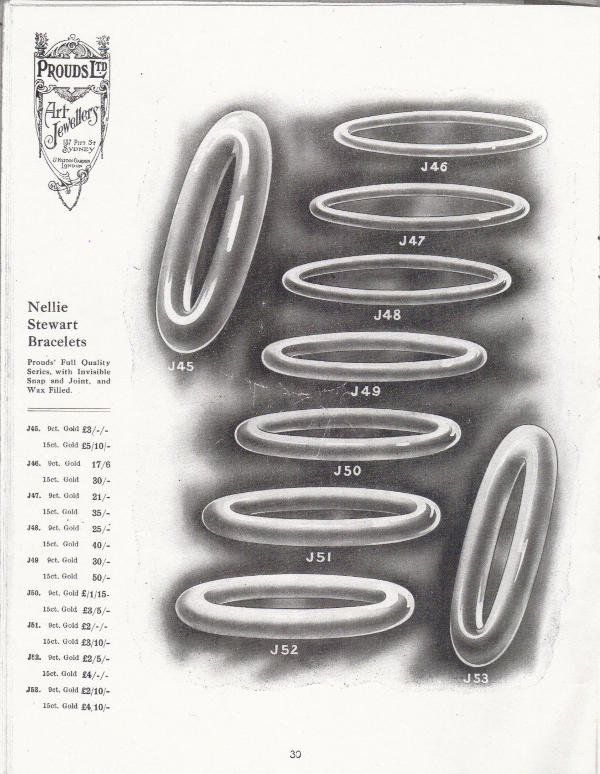

The bangles, however, would not have been readily accessible to an ordinary young woman. As shown in the 1912 Sydney Prouds Magazine, the smallest and thinnest 9ct bangle would have cost 17/6, and the largest and thickest 15ct one, £5/10. (Fig. 5)

[End Page 11]

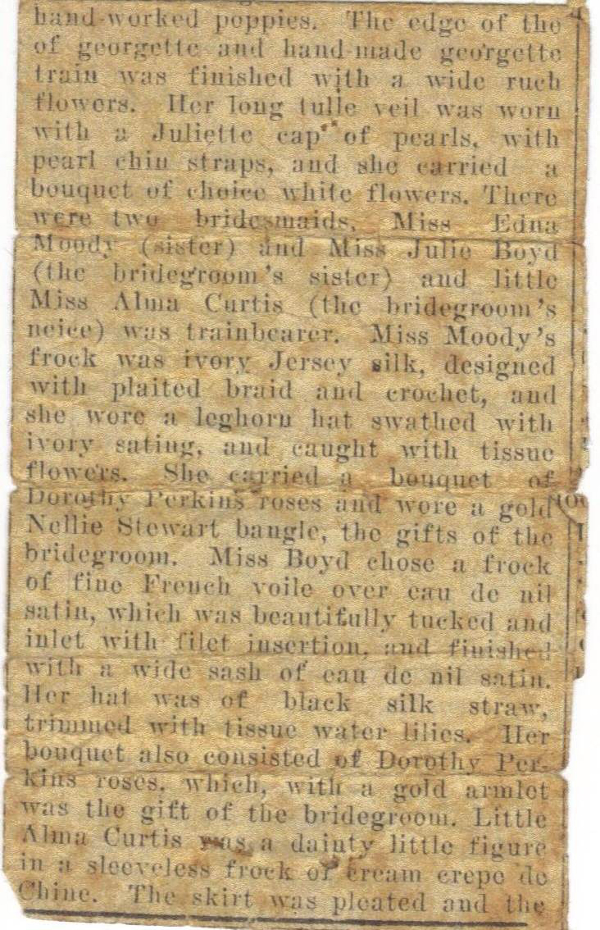

Women with incomes may have bought them for themselves, indulging in the pleasure of this coveted fashion accessory, thereby entering into a sense of association with the fashionable ‘set’. However, given what we have noted about wages, for the majority of women in the closing years of the nineteenth century such a purchase would have been out of the question. This is probably one explanation for the fact that, as indicated in relation to Fred Roels’s gift to his fiancé, the bangles became a popular courting gift. Although this was a style trend, a fashion craze that became particularly widespread and long lasting, at the same time the bangles retained for many women an aura of being “special” not only because they were associated with Stewart’s signature bangle, but because they were gold, and because they were frequently a gift from their sweetheart or fiancé. Just as ironically, the bangles came to be a common gift to women in bridal parties – that is, to the bridesmaids rather than to the bride (who may already have received one during courtship). Detailed descriptions of wedding apparel and party gifts were provided in the social or women’s pages of early newspapers and magazines, (‘Mirabel’ 1909a; 1909b, Clark 2003) and later they were seen in the photographic coverage of fashionable bridal parties. Figs. 6 & 7

[End Page 12]

[End Page 13]

In his study of gift-giving practices, Berking (1999) notes three patterns of behaviour and sets of motives in the evolution of the courting relationship: approach, confirmation and togetherness rituals. The presentation of a Nellie Stewart bangle by a man to his girlfriend would fall into the confirmation ritual, “mostly in the form of jewellery, little totems or more intimate objects, [which] try to bring certainty into an insecure situation by signalling that things are intended to stay as they are” (Berking 1999: 12). As a gift to a fiancé, the bangle would signify impending togetherness. Given as a groom’s present to the bridesmaid or female trainbearer, it may signal more than “appreciation of their support and assistance” (Pratt 1996: 18). However, the bridesmaid gift also signifies a rite of passage and publicly authenticates the new social position of the husband: “the wedding effects the outsider’s incorporation into the local group, with an accompanying exchange of gifts whose collective ‘meaning’ is not only to confirm his acceptance into the group, but also to bond him to the new symbolic order” (Berking 1999: 13). For bridesmaids, though, such gifts were and are reminders of their special role in the life of a woman friend or relative. In a further shift into the private lives of families, the bangles came to mark rituals such as christenings and events such as birthdays: “When Nellie Gill was a small child she was given a plain gold bangle (known as a Nellie Stewart bangle) which were very fashionable at the time” (Power 1995). These gifts to children, like those associated with romance, represent various changes in status: the christening event signifies a rite of passage in terms of a religious bond, rather than a romantic one; and the birthday signals a transition from one age to another. We also know that they were kept in families as heirlooms, and handed down through the generations, from mother to daughter, niece or friend (Skill 1973: 41, 42). In all of these contexts, gift giving is a question of emotional value much more than it is concerned with monetary value. The “preciousness” of the bangle in such uses of it comes to be measured only fleetingly in the association with Nellie Stewart, relatively insignificantly in the value of the gold itself, and largely in what the bangle comes to represent for the giver and receiver. When a bangle is inherited upon death of a loved one it becomes what Margaret Gibson describes as a “melancholy object”.

The melancholy object is a double signifier. It is the object (or objects) materialising and signifying the mourning of mourning. In other words, the melancholy object signifies the memory of the mourning and as such it is the memorialized object of mourning … However, the melancholy object as a memorialized object could also signify the incompletion of mourning – the reminder that grief never entirely goes away. The melancholy object is then the affective remainder or residual trace of sadness and longing in non-forgetting. (Gibson 2004: 289)

So in this regard, a Nellie Stewart bangle once belonging to a mother, now worn by a bereaved daughter, holds a multitude of functions and meanings that go further than the ritual event of the bangle’s exchange. It is in the continued wearing of that inherited bangle upon the arm of its new owner that the wearer remembers and perhaps re-experiences her grief. It is indeed a special kind of memory object.

Thus, while Australian and New Zealand women would have carried the tradition of the Nellie Stewart bangle for thirty-eight years, without knowing the private history of the original, the replica bangles became publicly associated with love, courtship and weddings; [End Page 14] privately given as tokens of commitment to a love relationship; treasured as mementoes of important relationships with other women; given to women to mark significant occasions; and passed down through families as remembrances of past feelings. The value of the Nellie Stewart bangles involved the transfer of a certain aura associated with Nellie Stewart and the public’s love for her, but for many people it also involved “intimately personal” associations with private expressions of love or affection, and public acknowledgement of those feelings. In this interplay between public craze and intimate uses – between style and expression, aura and value, personal and shared experiences – the deep emotional importance of the original bangle to Nellie Stewart and George Musgrove is invisible to their contemporaries, hidden from public view.

For Walter Benjamin, “The presence of the original is the prerequisite to the concept of authenticity … The authenticity of a thing is the essence of all that is transmissible from its beginning, ranging from its substantive duration to its testimony to the history which it has experienced” (Benjamin 1970: 222-3). When a Nellie Stewart bangle was a fashion accessory for the wearer, the associations with Nellie’s signature bangle may well have been the most important thing about the replica for the wearer, the residual aura that came to the reproduction from that famous original. But when the replica bangles become associated with all these other uses in the intimate lives of giver, receivers and inheritors of them, the fact that they are replicas falls away and the sense of “authenticity” is invested in the replica objects due to their current or past associations with the personal histories of individuals, couples and families. The replica objects begin to enter into a value exchange of their own.

[C]ertain symbolic continuities can remain as objects might continue to be thought of and named as belonging to former owners even though they are now worn by, used or in the possession of other people. Through death, the subject-object relationship enters into a new phase of distribution, attachment, ownership or custodianship and the question of value inevitably arises. (Gibson 2010: 55)

In such ways, we need to notice that it is too easy to allow the participation of an object (or a story) in a culture of celebrity to occlude the other cultural values that come to accrete around it. In the case of Nellie Stewart bangles degrees of value slide around between emotional, monetary, fashion and celebrity associations for each woman who has such a bangle in the period that coincides with Stewart’s active life as a performer, social icon and example of public morality in relation to her humanitarian work. There is no fixed set of associations that attend the replica bangles. Each becomes an object with its own story and those many stories frequently leave the original bangle behind as the bangles become treasured personal possessions. The Nellie Stewart bangle had acquired an independent popular cultural life.

During the period of her celebrity Nellie Stewart seems to have been particularly highly regarded by women. On the reverse of a Nellie Stewart postcard (held in the Mitchell Library Pictures Collection, PXA857) dated July 9, 190(?), addressed to presumably a young woman, her friend and professional colourist writes: [End Page 15]

Dear Kit,

Be sure and send that head of her to be colored for your pendant. Hope you haven’t this one of her. I colored it of course, it is an old one, I think, but pretty. 7/6 the half dozen… take such a time to do, the color always sinks in on the plate of any kind & you have to go over them so many times.

‘little Nell”

The Victorians were famous for their obsession with sentimental jewellery (Cooper 1972) and well into the early twentieth century it remained a very popular practice to insert the photo of a loved one inside a locket either worn as a necklace or even a bracelet or brooch. This is, therefore, a particularly revealing inscription. If it was traditional only for loved ones to be held in the intimate space of a locket and worn around one’s neck, then this demonstrates how loved and adored Nellie Stewart really was, especially by women. Not only did her name attach itself to a beloved bangle, but in this case her image is carried with the wearer against the heart. This goes beyond the predilection for the prized collecting of theatrical postcards alone, and demonstrates both an active and creative engagement with the iconicity of celebrity on the part of the fan. “The portrait of the actress similarly signifies the presence of her ‘real’ body and the fantasy for the spectator of owning a part of that body through possessing the portrait. Portraits of actresses also suggest the absence of their real bodies, leaving spectators with a longing for the missing actual thing” (Engel 2009: 282). This example is truly a demonstration of the act of possession in a state of absence. Stewart acknowledges this deep affection held towards her by women, and she expresses her gratitude:

And I am thankful – oh, more thankful than I can say! – to those tens of thousands of good people who have made my success possible, and who long ago adopted me into their hearts, and who have kept me there…It is the greater joy to me because so many of them have been women. It always hurts me when I hear that such and such a person is a man’s woman – meaning by that that she is indifferent or hostile to fellows of her own sex. Times beyond count I have been helped over rough places by the unobtrusive sympathy of women.

With Australian girls I know that I am among friends; it has always been so. (Stewart 1923: 3, 4)

One explanation of Stewart’s popularity amongst women might be found in the theories of Andrew Tudor and Leo Handel. Their typology of audience /star relationships suggests that people’s favourite stars tend to be of the same sex as themselves. This would certainly apply in their classification of degrees of identification and affinity with the admired star, with the popular wearing of bangles falling within the category of “imitation” and role modelling (Tudor & Handel in Dyer 1998: 17, 18).

Many Australian photographs of the twenties reveal women frolicking in their woollen bathing costumes sporting a Nellie Stewart bangle, usually on their upper arm. The opportunities for display in this context, not just of the body, but of adornment of the body, were great in the context of an emerging Australian beach culture. The frequency of such images in the period would also seem to indicate that the bangles were not taken off for [End Page 16] swimming, and therefore always left on the arm (much like Stewart’s). This public display of the bangle could be interpreted in several ways, none exclusive of the others: first, that they were fashionable young women; second, that perhaps they were attached, i.e. a gentleman had signalled his intentions; and third, as a public statement of identification with the apparent independence of Nellie Stewart. Young women willing to be seen in such revealing garments were willing to reveal more than was customary of their private selves in public, just as the admired performer might. This can be read as fashion performance, but also as recognition, however intuitive or considered, that being a woman in public is always a question of performance and the more so if a woman or group of women steps outside of the expected frames for how women’s bodies should be displayed, used or enjoyed by themselves. These are images of women having fun together, making public use of their bodies for exercise and enjoyment, whether or nor not for flirtation and/or social standing.

The emergence into the public knowledge of the facts of Stewart’s long-term de facto relationship and unmarried motherhood might have changed how she was viewed by many of her public. Stewart was at pains to defend the morality of the private theatrical environment in which she grew up and spent the entirety of her life, being only too aware of the suspicious public perception of actresses:

There is a queer idea prevalent that the players of forty or fifty years ago were all bohemian in the bad sense – reckless and riotous people. I never found them so. There was sound comradeship among them, and with that an honest joy and pride in their profession. They were far homelier than we of the theatre are now. (Stewart 1923: 30)

Engels (2009) explores discourses of tainted morality around actresses of the eighteenth century. These anxieties tended to persist even into the twentieth century (especially in the early years of Hollywood). By virtue of their profession being based on techniques of bodily display, and various representations of femininity as excess, there emerges a slippage of meaning in the consumption of the actress as commodity. The blurring of the distinction between actress and role is embedded in such polarised performances as, “good or bad, comic or tragic, prostitutes or virgins, mistresses or mothers” (Engels 2009: 284). An actress’s life on and offstage acquired interest for fans, despite the only access they had to either was necessarily mediated. A month before she died Stewart was the subject of a feature article in Australian Home Beautiful (May 1931). The article includes several photographs of the garden and interior of Stewart’s home, “Den o’ Gwynne”, complete with theatrical memorablia on display, and a very youthful looking Stewart seated at a harpsichord, bangle in full view. Marshall (2006: 317) references Charles Ponce de Leon’s work on how “celebrity journalism changed, from the nineteenth to the twentieth century from reporters piecing together stories from people knew famous people to direct interviews with famous people in their private homes.” The women’s magazine article demonstrates this move ‘literally’ towards gaining access to a supposed private interior of the individual, rather than prior focus on Stewart a key player in the J. C. Williamson company. It is also worth noting Stewart’s own playful naming of her house as the home of Nell Gwynne – indicating she herself identified with her alter ego, the one her public too learned to identify. However, very little is actually revealed about Nellie Stewart. Far from [End Page 17] accessing “the real” person behind the celebrity image, as many contemporary women’s magazines claim to do, this article serves only to build even more on the constructed Gwynne identity, but presents it as a natural part of the actress’s personality, in tandem with a number of her other roles:

Here, on the threshold of the little home she loves so well, she steps simply and naturally into the title-role of a little one-act piece, “Nellie Stewart At Home,” by Herself. Or perhaps it would be more correct to say that the role is played by a number of lovely women, Nell Gwynne, Maggie Wylie, Sweet Kitty Bellairs, and all the rest of the goodly company. For one realises that they… are really part of Nellie herself, that magic personality whereby she has held for so many years, and still holds, the hearts of the Australian public. (Cooper, 1931: 10)

In contrast, two articles in The Sketch detail a different approach: the first ‘Miss Nellie Stewart’ (1895: 154), about a decade into Nellie Stewart’s fame, consists of two lengthy paragraphs on Miss Stewart’s travel plans whilst abroad in Europe, her critical opinion of Australian versus English audiences, and the sacrifices she believes one should make for one’s art; the second, ‘An Australian Manager in London’(1897: 135), is a full-page interview with George Musgrove, detailing his professional achievements and upcoming productions. Stewart is mentioned by Musgrove only in passing as a skilled and well-known player with a wide repertoire, but the layout features a large photograph of her centre-page, with the written text encircling her image. The caption reads “Miss Nellie Stewart, Leading Lady at the Shaftesbury Theatre”. The reader’s attention is at once directed towards her image, but the article itself is not about her, but her manager, the impresario behind her fame, and the man to whom she is ‘attached’. Even so, there is no mention of a personal relationship and this at a time several years after the birth of Nancye. This early media coverage definitely focuses on their achievements, rather than any speculation on intimate personal relations. In this regard, these two nineteenth century texts conform to Leo Braudy’s theory of the four elements of fame: “a person, an accomplishment, their immediate publicity, and what posterity has brought them ever since” (Braudy 1987: 15). It is unfortunate that Stewart did not make any musical recordings, unlike her contemporary, Dame Nellie Melba who made over one hundred. Should she have done so, these audio recordings would have outlasted the ephemerality of her popular celebrity in the theatre. The longevity of a commercial recording has the capacity to reach others beyond the lifetime of the person recorded, through the public’s consumption of repeated reproductions. The reason for this lack may have been because Stewart was an actress first and a singer second. Melba’s profession as a classical opera singer, favoured her for posterity, because of the elite and enduring status of the art and her further audio documentation. The fashion for light opera and pantomimes fluctuated with publics, as new forms of popular entertainment, namely cinema, replaced them. Shortly before she died, Stewart made four 78 records (now held in the Mitchell Library in New South Wales), reprising segments of her role as Nell Gwynne and including an address to her public. The only film she made, Sweet Nell of Old Drury (Longford & Musgrove 1911), based on her highly successful theatrical role, sadly does not survive. Richard de Cordova [End Page 18] (2006: 101) observes that it was some time before there was a perception that people “acted in films”.

The film D’Art’s supreme contribution to the contention that people acted in films probably did not come until 1912 with the release of the filmed version of Camille starring Sarah Bernhardt … The world’s greatest and most famous actress had (by many accounts at least) had become a photoplayer, thus blurring – for an instant at least – all distinctions between the moving picture and the legitimate theatre.

Stewart had sometimes been hailed as Australia’s Bernhardt, and both had played the role of Camille. It seems Stewart’s transition to film in this regard appears to mirror that of Bernhardt’s, in that both actresses were widely recognised for their excellent theatrical skills and had attracted much public attention. Each had made their name on the stage first, and played out their favoured theatrical roles in filmed versions. Each was paid large sums of money to appear in the films. However, Stewart, did not continue down this path, and sought to return to the stage.

Whether being apparently too soon forgotten in popular culture was in anyway associated with her acquisition of a more ambiguous moral status than she had prior to her autobiography is unclear. Certainly, actresses had already for some time taken advantage of writing their memoirs as a publicity technique to represent themselves in a positive light in order to counter any scandalous rumour or unfavourable discourse circulating around their name and image (Engels 2009: 284). We can imagine that for some women their Nellie Stewart bangle might have become (privately) more precious as a “standing in” for the difficulties of life for women, or, as may have been the case with the women on the beach, even more endowed with emergent nineteen-twenties qualities of stylish independence already associated with Stewart. For others the bangle may have become “tainted” by association with the public revelation of Nellie’s Stewart’s “real” private life, as opposed to the performance of being Nellie Stewart necessitated by Stewart’s being herself a public commodity, just as her bangle had become. However, it seems apparent that once Stewart passed away in 1931, and despite plain gold bangles retaining their status as ritual gifts (particularly for children’s birthdays), they gradually ceased to be known as Nellie Stewart bangles, as a younger generation reached marrying age and the name Nellie Stewart was no longer as familiar. Her celebrity, which had spanned four decades, had come to an end, and so with it the public’s romantic gesture of giving the bangles as a wedding gifts.

A Bangle’s Demise

So what became of that bangle? Below is an extract from Stewart’s will:

I DIRECT that my remains shall be cremated together with the gold bangle which has been on my arm for over thirty years… (Stewart in Skill 1973: 171)

Rather than its being passed on to her daughter, as sentimental jewellery customarily was, and as other Nellie Stewart bangles have been, Stewart instructed it to be destroyed with [End Page 19] her body. She wanted her most intimately precious possession to go to her death with her, as a testament to the depth of the relationship that led to Nancye’s birth.

Contrary to her wishes, however, it was removed from her arm after her death. It was not cremated with her remains as “this was impracticable under the New South Wales law” (Evening Post, 1931, p 13). It was delivered to Nancye, along with bequeathed personal effects and jewellery. By then, Nancye was herself an actress and married to the actor, Mayne Lynton. Had it not been for State law prohibiting the bangle’s cremation, Nancye would have been deprived of the transference of memory that this melancholy object facilitated for her, while other daughters inherited “Nellie Stewart bangles” along with the romantic stories of childhood memories of their mothers. Stewart, on the other hand, had wanted to take her bangle with her as a powerfully private symbol of her love for George that had been secretly acknowledged through the ever-present bangle. For Stewart, the bangle was clearly a public/private interface of deep significance. For almost forty years she was unable to declare her love for Musgrove publicly, but she could wear the bangle, thus creating a personally sacred object. As the bangle had never left Stewart’s arm in her lifetime, this item attracts special value as an intimate object of the body (Gibson 2010: 59). Given what Stewart attempted to instruct in her will, the story of her bangle has much to say about the constraints on women’s lives in her time. Even being a major celebrity, a style icon adored and emulated by millions, did not allow her to be free from the restrictions placed on women by law and morality working together. But Stewart’s bangle can also be seen to be a representation of her resistance.

In a final twist, the bangle was taken by flames in the end. In a postscript to a 1974 interview with Stewart’s biographer, Marjorie Skill, she adds:

Nellie’s grandson, Michael Lynton, has told me recently (February, 1975) that the original and famous ‘Nellie Stewart Bangle’ was destroyed in the terrible fire that killed fifty people in a holiday resort at the Isle of Man in August, 1973 – the month and year of Nancye Stewart’s death in Mosman, Sydney. (Skill 1975: postscript)

The bangle’s centrality in Nellie’s Stewart’s emotional life was such that we can only guess at how she might have reacted to this. When the great San Francisco earthquake struck, Musgrove’s company was touring. All the sets, costumes and props were destroyed in the fires so Stewart sold all her jewellery to assist the company to return to Australia. She must have owned a significant amount of valuable jewellery for such a gesture to make a difference, but even in that crisis she did not sell her bangle – any more than one might sell a wedding ring. The bangle was imbued with symbolic value, far greater than that of its market value. The decision not to sell represents a moral economy: “… taken-for-grantedness values about what possessions can or cannot be sold in exchange for money” (Gibson 2010: 55). Margaret Gibson points out in her research on the significance of objects of bereavement, that the disposal of, “… some objects (inalienable) have a status which places them beyond monetary calculation and market exchange, whilst others (alienable) are more easily transacted in exchange relations” (Gibson 2010: 55). So too, it was with the bangle, an inalienable personal and priceless object.

The bangle stood for Musgrove’s desire to marry Stewart, symbolising a disguised “marriage”. Her autobiography is dedicated to him: ‘A great and good man’. In a further [End Page 20] intensification of the dilemma posed by the ambiguity of their relationship, and the tensions between their private and public lives, their inability to legally marry resulted in another disguise: in his will, Musgrove refers to Nancye Stewart as his “adopted daughter”. Even Stewart remarked that this was strange. But Nancye was the illegitimate child of Musgrove, and her actual status is hidden by the category of ‘adopted’. Early in Stewart’s book she frankly declares, “I have known one lover, and only one, but I have had many splendid men friends” (Stewart 1923: 39). At a time when divorce was not readily available and when considerably more conservative social mores prevailed, perhaps this was Musgrove’s effort to preserve both women’s respectability[4] or perhaps his own morality, remaining as he was a married man. Stewart fell pregnant to Musgrove on his visit to her in London, in August 1892. Stewart had already been working in England and had taken up residence in Devonshire before this. Musgrove then spent much of his time in America on business. Throughout her pregnancy she lived frugally for ten months in a village called Chingford, in Essex where Nancye was born. There is no doubt regarding the paternity of Nancye, given these details related by Stewart (1923:103-104). George had already left for Australia when Stewart gave birth. She followed him shortly afterwards and arrived in Melbourne when Nancye was three months old, and began performing heavy schedules again with J. C. Williamson in September. In this regard, the pregnancy was concealed from her publics (both English and Australian) but there does not seem to be any effort on their part to hide Nancye from view, as she travelled with them as part of the wider theatrical family. I have not encountered any printed scandalous gossip concerning Musgrove or Stewart. On the contrary, Stewart, especially, was held in very high regard.

Nellie Stewart’s ashes are buried in the family grave at Boroondara cemetery in Kew, “then the cemetery most favoured by Melbourne’s fashionable world” (Skill 1973: 158). The grave bears a large guardian angel in the likeness of Stewart, who is wearing the bangle. (Fig. 8) The statue was there before Stewart’s death, tending her mother and stepsister’s resting places. When I visited the gravesite in April 2005 rose bushes had recently been planted within it. [End Page 21]

[End Page 22]

The memorial plaque in Sydney’s Royal Botanic Gardens erected by the Nellie Stewart Memorial Club, was once within The Nellie Stewart Garden of Memory. (Fig. 9) This plaque also shows the bangle, although it is braided and decorated, and thus not in the style of an “authentic” Nellie Stewart bangle.[5] Originally this memorial was located in a gazebo surrounded by two thousand rose bushes in her honour, befitting the ‘Rose of Australia’.[6] There is even a waltz, aptly called Rose of Australia, composed by Nellie Smith (1913), bearing a dedication “by kind permission” to Nellie Stewart and an art nouveau garland of red roses around an image of Stewart on the cover. This Grecian-inspired Talma photograph, taken in 1908 (when Stewart was fifty-three) exudes an air of innocence and simplicity. It was not uncommon for sheet music of the time to bear dedications to famous persons on the cover. Combined with a photograph of the star, this would aid in sales of the music and continue to build on the celebrity of the artist. This also applied to named performers pictured on covers, who were famous for singing a particular song, thereby acting as important vehicles in the promotion of the song (Marshall 1997: 150-151).

In a photograph taken by Australian photographer, Frank Hurley, during the 1940s, we see two young women looking at the plaque inside the shady gazebo. Sadly, the gazebo is long gone and there are no more roses, nor the Garden of Memory. Nellie Stewart’s memorial lies hidden behind some pots in the Herb Garden. When I visited, the section of the gardens where two thousand roses once grew was under reconstruction, with an accompanying sign: “What’s happened to Sydney’s rose garden?” explaining that the older style roses and garden design were being replaced by roses and a design more suitable to Sydney’s climate, conditions and fun lifestyle. This was also explained on the Botanic Garden’s website. Neither source gestured towards any original connection with Nellie Stewart. Perhaps Nellie Stewart’s flower or plant should now be rosemary. It is strangely befitting that she is located in the herb garden, with rosemary’s traditional meaning of ‘remembrance’. And perhaps they should also plant some Queen’s Rocket, being the Victorian plant to signify fashion (Greenaway 1884), as no other Australian woman of her time had such an impact on fashion as the kind that Nellie Stewart did. Even the Reverend Doctor Micklem declared at her funeral, “An artist such as Nellie Stewart fulfilled our desire for beauty and performed a service to the whole world” (Micklem in Skill 1973: 158).

On Stewart’s memorial plaque in St James’s Church in King Street, Sydney, where she was christened and her funeral held, are the last words of Nell Gwynne from Sweet Nell of Old Drury, with whom her public image became synonymous: “Memory will be my happiness”. This line also ends her autobiography and accompanies an autograph I have of hers. The second part of the line reads, “For you are enshrined there”. Its sentiments are directed to her audiences who brought her to stardom, but also dedicated to George Musgrove. So there is another strange, sad irony, in that she was a woman who held the hearts of many, at a time when there were none who did not know her name, but her memory has now faded almost entirely from public view.

A young Nellie Stewart (as Nell Gwynne, with her oranges) looks out at us on a 1924 Australian 50 pence stamp, celebrating Rose Day, Sydney, saying, “’Sweet Nell’ thanks you”. This can be taken to indicate the love and gratitude Stewart felt towards her public. But at the same time, like the plaque in St James’s, this stamp, released just after the publication of her autobiography, associates her not only with a famous role, but with the great actress and great mistress of her time – Nell Gwynne who was never able to marry her lover, the king. The conflation of actress with role by the public is not something new. “The highest [End Page 23] praise for a star actress in eighteenth-century commentaries was that she consistently became the person she impersonated, alleviating the strain between public and private identity but more significantly between uncertain rank and recognisable status” (Nussbaum in Engel 2009: 282-283). The confusion between Nell, the character and Nell, the performer, was possibly also a strategic ploy on the part of her promoters. By forging a fantasy identity for consumption, they thereby blurred the boundaries of authenticity and illusion (Engel 2009), and perhaps protected Stewart’s ‘real’ status as unmarried mother and sweetheart to a married man. Stewart was also remembered in 1989 on another stamp – this time with J. C. Williamson, her employer – commemorating Australia’s theatrical history.[7] Still, Stewart and Musgrove do not acquire a public presence, side by side. Our once loved Australia’s public idol appears without the man who privately adored and idolised her, their relationship still hidden.

Nellie Stewart bangles existed as enduring artefacts at the centre of a range of social and cultural relations for over forty years. They marked the transition from single maiden to betrothed woman, from newborn child to child of God, from one birthday to another, and from sentimental memory objects into objects of mourning. They are also indicative of the Industrial Revolution’s exploitation of a number of historical events, namely the Victorian gold rushes, and the widespread and largely uncontrolled manufacture and merchandising of famous persons’ identities via objects that bore their name. The original bangle’s history is now uncovered as being much more than a signatorial feature of Stewart’s celebrity, but is revealing of a unique set of social circumstances, that manifested in a body adornment which would be emulated by thousands of fashionable women, happily unaware of the sad disguise that first bangle enacted.

In closing, this excerpt from a poem by Dorothy Hewett (1966) Legend of the Green Country is apt. Through the figure of her grandfather, it embodies the gold rush era, the working classes, the distinction between high and popular culture, and the love for Sweet Nell:

Yet sometimes in the dark I come upon him in his chair,

A book lying open on his knees, his eye turned inward,

And then he sings old songs of Bendigo and windlasses,

And tells me tales of Newport railway workers, Nellie Melba

Singing High Mass, and how he read all night in Collingwood.

Voted for Labor and fell in love with Nellie Stewart.

[1] Stewart took pity on a young man called Richard Goldsbrough Row who was desperately in love with her, and regrettably married him on 26 January, 1884. She realised her foolishness, later calling it “a girl’s mad act”, and sailed for New Zealand a few days later. This marriage was not dissolved until 1900.

[2] Before this, pinchbeck was far more common. The Powerhouse Museum in Sydney holds a gold spade pin, a reflection of some of the mining-themed jewellery that was produced at the time. There were other gold rushes in the Americas and Africa in the same period. Thus, gold became more common and affordable in Britain and Europe as well.

[3] Although there was no requirement for hallmarking in Australia at that time, they would probably have born a maker’s mark if produced by a reputable jeweller. [End Page 24]

[4] And although he was a theatrical manager, or perhaps because he was, it may also be the case that Musgrove was sensitive to the bohemian and “not quite respectable” connotations of the theatre, given that both Nellie and Nancye were performers.

[5] The image of Stewart for this plaque was modelled on her niece rather than on herself, and unfortunately the date of her death is incorrect: 1932 instead of 1931. Stewart’s reality is in this instance obscured by historical mis-takes.

[6] Throughout the Victorian period roses generally meant beauty and love, although there were many variants depending upon the type of rose concerned (Bryant 2002).

[7] To appear on an Australian stamp more than once is significant and indicates that archival history, at least, has not forgotten her. Stewart’s portrait is held in the National Gallery of Victoria. [End Page 25]

References

Albrecht, Kurt (1969) 19th Century Australian Gold and Silversmiths, Melbourne: Hutchison.

‘An Australian Manager in London’, The Sketch, Nov. 17, 1897, p. 135.

Benjamin, Walter (1970) ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’, Illuminations, trans. H Zohn, Jonathon Cape, London, pp. 219–244.

Berking, Helmuth (1999) The Sociology of Giving, trans. Patrick Camiller, London: Sage Publications Ltd.

Braudy, Leo (1997) [1986] ‘Introduction’, The Frenzy of Renown: Fame and its History, New York, Vintage, pp. 3-18.

Bryant, Katherine (2002) The Language of Flowers

http://home.comcast.net/~bryant.katherine/flowqr.html (accessed 15/10/06)

Cavill, Kenneth, Cocks, Graham & Grace, Jack (1992) Australian Jewellers, Roseville: CGC Gold Pty Ltd.

Chisholm, Alexander Hugh (1972) Transcript of interview recorded June, 19, Sydney: National Library of Australia.

Church Gibson, Pamela (2012) Fashion and Celebrity Culture, London, Berg.

Clark, Cathy (2003) ‘Wedding Bells’ The Myers Family History, Whangarei

http://www.myers.orcon.net.nz/wedding.html (accessed 12/02/05)

Coney, Sandra (1995) I Do – 125 Years of Weddings in New Zealand, Auckland: Hodder Moa Beckett.

Cooper, Diana & Battershill, Norman (1972) Victorian Sentimental Jewellery, Newton Abbot: David and Charles.

Cooper, Jonathan (April, 2005) of Coopers of Epping Antiques, est. 1951, 14 Bridge Street, Epping, Sydney (personal conversation).

Cooper, Nora (1931) ‘Nellie Stewart at Home’, The Australian Home Beautiful, Vol. 9, No. 5, May, pp. 9-14.

Davison, Graeme – Melbourne’s Golden Mile, Melbourne: Melbourne Convention and Marketing Bureau.

De Cordova, Richard (2006) ‘The Discourse on Acting’, in P. David Marshall (ed.) The Celebrity Culture Reader, New York, Routledge, pp. 91-107.

Duveen, Geoffrey & Stride, H.G. (1962) The History of the Gold Sovereign, London: Oxford University Press.’

Dyer, Richard (1998) Stars, 2nd edition, London, British Film Institute.

Ellis, Edward (1888) Pets of the Public: A Book of Beauty, Sydney: Ellis.

Engel, Laura (2009) ‘The Muff Affair: Fashioning Celebrity in the Portraits of Late-eighteenth-century British Actresses’, Fashion Theory, Vol. 13, Issue 3, pp. 279-298.

Gere, Charlotte (1972) Victorian Jewelry Design, Chicago: Henry Regnery Company.

Gibson, Margaret (2004) ‘Melancholy objects’, Mortality: Promoting the interdisciplinary study of death and dying, 9: 4, 285-299

Gibson, Margaret (2010) ‘Death and the Transformation of Objects and Their Value’, Thesis Eleven, 103: 54, pp. 54-64.

http://the.sagepub.com/content/103/1/54 (accessed 7/5/14) [End Page 26]

Greenaway, Kate (1884) ‘Language of Flowers’, Prints with a Past

http://www.printspast.com/selected_print.asp?PrintID=10780035&Return=language-flowers-greenaway.htm (accessed 15/10/06)

Hewett, Dorothy (1966) Legend of the Green Country

http://wawriting.library.uwa.edu.au/cgi-bin/nph-dweb/dynaweb/wawriting/hewett003/

Hume, Fergus (1886) The Mystery of a Hansom Cab, Melbourne: Kemp and Boyce.

Hurley, Frank (1910 – 1962) Hurley Negative Collection

http://nla.gov.au/nla.pic-an23478328

Joel, Alexandra (1998) Parade: The Story of Fashion in Australia, Sydney: Harper Collins.

Kelly, Veronica (2004) ‘Beauty and the Market: Actress Postcards and their Senders in Early Twentieth-Century Australia’, New Theatre Quarterly, Vol. 20, No. 2, May, pp. 99–116.

Lipton, Martina (2011) ‘Imbricated Identity and the Thatre Star in Early Twentieth-Century Australia’, Australasian Drama Studies, April, pp. 126-147.

Maguire, Roslyn (2004) ‘Italian Jewellers in New South Wales’, Australiana, Vol. 26, No. 3.

Madow, Michael (1993) ‘Private Ownership of the Public Image: Popular Culture and Publicity Rights’, California Law Review, January 1993, 81 Calif. L. Rev. 125.

http://cyber.law.harvard.edu/IPCoop/93mado2.html

Marks, Kenneth R (April 2005) of Percy Marks, est. 1899, 60-70 Elizabeth Street, Sydney (personal telephone conversation).

Marshall, P. David (1997) ‘The Meanings of the Popular Music Celebrity: The Construction of Distinctive Authenticity’, Celebrity and Power: Fame in Contemporary Culture, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, pp. 150-184.

Marshall. P. David (2006) ‘Intimately intertwined in the most public way: Celebrity and journalism’, in P. David Marshall (ed.) The Celebrity Culture Reader, New York, Routledge, pp. 315 – 323.

Mason, Anita (1973) An Illustrated Dictionary of Jewellery, Berkshire: Osprey Publishing Ltd.

Mauss, Marcel (1973) ‘Techniques of the Body’, Economy and Society, Vol. 2, No. 1, pp. 70-87.

Meyer, Franz Sales (1894) A Handbook of Ornament, London: Batsford.

‘Mirabel’ (1909a) ‘The Social Sphere’, The Observer, Auckland, Saturday, September, 4, pp. 8, 9.

‘Mirabel’ (1909b) ‘The Social Sphere’, The Observer, Auckland, Saturday, December 18, p.8.

‘Mirabel’ (1909c) ‘The Social Sphere’, The Observer, Auckland, Saturday, December 25, p.8.

‘Miss Nellie Stewart’,The Sketch, Aug, 14, 1895, p. 154.

New South Wales Police Gazette and Weekly Record of Crime, (1909) Wednesday, 20 May, p. 204.

O’Day, Deirdre (1982) Victorian Jewellery, London: Charles Letts Books Ltd.

Power, Bryan (1995) ‘Nellie Gill Remembers’, RLHP Local Stories http://www.rlcnews.org.au/stories/stamford_park/gill_nellie_gill_remembers.php

Pratt, Douglas (1996) A New Zealand Guide to Wedding Ceremonies and Birth Celebration (3rd Ed), Orewa: Collom Press.

Reserve Bank of Australia (2005) Museum of Australian Currency Notes

http://www.rba.gov.au/Museum/Displays/ [End Page 27]

Skill, Marjorie (1973) Sweet Nell of Old Sydney, Sydney: Urania Publishing Company.

Skill, Marjorie (1975) Postscript to a transcribed conversation with Skill, recorded 19 February, 1974, National Library of Australia.

Smith, Nellie (1913) Rose of Australia Waltz

http://nla.gov.au/nla.mus-an6223227

Stewart, Nellie (1923) My Life’s Story, Sydney: John Sands Ltd.

“Sweet Nell’s” Bangle, Evening Post, Vol. CXII, Issue 55, 2 September 1931, p. 13.

Woodly, Robert (April, 2005) Pictures Staff, Mitchell Library, State Library NSW (personal conversation)

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank Dr Margaret Gibson, Assoc Professor Pat Wise and Ms Sue Jarvis for their most helpful reading and detailed suggestions for revisions. I would also like to thank Chrys Spicer for escorting me to Nellie Stewart’s grave and the hospitality he showed me whilst visiting Melbourne. [End Page 28]