Introduction

As the field of Popular Romance Studies grows, greater emphasis needs to be placed on how and where popular romance scholars gain access to research materials, specifically in regard to academic libraries. While there is a growing amount of information available freely on the internet, relying solely on web-based sources can leave gaps in research. Libraries provide access not only to proprietary subscription journals, databases, and books, but also to rare and fragile primary source material in their special collections.

Some attention has been given to the collection of popular romance1 works in public libraries in the United States (Adkins et al.), but very little has been documented on the collection development practices of university libraries, which facilitate access to primary and secondary sources for popular romance studies. Unlike the U.S., Australia remains a forerunner in popular romance collection development. In 1997, Juliet Flesch wrote about the University of Melbourne’s Australiana collection beginning to include romance novels written by Australian and New Zealand authors, although they do not seek a comprehensive but rather a representative collection (Flesch 120-121). However, this is vastly more than can be said for academic libraries anywhere else in the world.

Most university libraries actively purchase resources that support departments on their campus—with shrinking acquisitions budgets, this is often all that libraries can afford to collect. Despite Nora Roberts’ donation to McDaniel College to establish a minor program, Popular Romance Studies has yet to gain a toehold as a major department on any university campus in the United States, which means that collections in this area tend to be haphazard, at best (“Nora Roberts Foundation”). In addition, the cross-disciplinary nature of this field makes purchasing new sources difficult for librarians who serve as liaisons to specific academic disciplines and have only the power to buy materials for their assigned departments. Library special collections may collect popular romance materials, despite the lack of a major department on campus; however, this is often dependent on donations rather than a commitment of funds toward a comprehensive collection (Sewell 459; Flesch 121).

With no cohesive vision for which items to collect and little justification for fiscally supporting popular romance studies material, vital monographs, papers, and articles are not being preserved by libraries for future researchers’ use and may, indeed, be lost from record entirely. The question of how to assure ongoing access to resources that are valuable to this field is one that must be acknowledged and addressed as soon as possible.

Defining Library Collections

There are multiple models for who is responsible for collection development in university libraries. The most common model is that each librarian specializes in different academic disciplines and serves as the liaison to that department or set of departments. What this means is that those who are liaison librarians are responsible for all library instruction, reference consultations, and collection development for their assigned departments. Note that with each librarian tied to major departments, collection development becomes problematic for areas such as Popular Romance Studies, which is not a major or minor available at most universities. An exception to this model are librarians who work in special collections, which focus on collecting and preserving rare and valuable items for future researchers, whereas subject liaison librarians typically collect for their library’s general collection.

Collection development may be carried out by different librarians, depending on the practices, policies, and organizational model each library employs; however, the process and goals remain essentially the same.

Collection development is a term representing the process of systematically building library collections to serve study, teaching, research, recreational, and other needs of library users. The process includes selection and deselection of current and retrospective materials, planning of coherent strategies for continuing acquisition, and evaluation of collections to ascertain how well they serve user needs. (Gabriel 3)

The strategies involved in planning for continuing acquisition of library materials must inevitably touch on the deep budget cuts most U.S. universities and their libraries have faced in the last decade. What libraries can afford to spend money on has become increasingly narrow. In the course of collection development, librarians have to ask themselves what the library cannot do without—what make up the core works in each area—so that the library has the essentials for students and faculty to use for their research. The fundamental principle of a core collection is that “certain books and films are standard classic titles that are at the very heart of a library’s collection and form the foundation upon which a library’s collection is built” (Alabaster vii).

However, what has also become an issue in the field of Library and Information Science is the very definition of a collection. While collection development for librarians is a “process of dealing with the collections they acquire, maintain, and evaluate. These three areas of collection development have undergone extensive technological expansion in the past few years and this has lead to a conflict with the more transitory nature of genre literature” (Futas 39). What we see is that collections have been traditionally defined by four criteria: ownership, tangibility, a distinct user community, and an integrated retrieval system (Lee 1106). The proliferation of freely available information online, combined with users from across the globe entering the library through search engines such as Google Scholar, instead of patrons from the home institution finding library sources through the traditional catalog, makes it difficult for librarians to define which users they are serving primarily and how best to facilitate that service so users find the most relevant sources. Compounding that issue are the many electronic refereed journals that are open access, such as the Journal of Popular Romance Studies. It is online and available to anyone to view, so can every library consider it part of their collection, or can none of them? It is not tangible and the library will never own a physical copy to keep on their shelves, so the question becomes as nebulous as trying to define a collection.

Moreover, the research status of a library—very high research activity, high research activity, etc—is partially determined by counting the volumes available in the library, meaning ownership plays an important role in this determination. Unfortunately, this is not an accurate representation of how patrons use the library. Circulation statistics for books and other physical items are going down, and use of online sources such as article databases and ebooks is skyrocketing. However, this kind of content is neither tangible nor owned. In many cases, it is leased, licensed, or rented, but it is not owned as part of a library collection, and if a library gives up a subscription, the back files often go with the subscription, unlike a print journal where the older volumes would still belong to the library.

Without the constraints of the traditional criteria, the best definition for a collection is that it is an “accumulation of information resources developed by information professionals intended for a user community or a set of communities” (Lee 1106). How one defines the community or communities one serves is a matter decided by the administration of each library or university.

Who Should Collect Popular Romance?

With shrinking budgets, librarians must decide what is essential to their collections and spend what monies they have on those items. The audience or community most academic librarians serve is the faculty and students of their home institution. With that in mind, the first priority has to be to buy for the departments on campus. So far, only McDaniel College has a department on campus with a popular romance minor, and thus a mandate to purchase materials in that area. There are other universities who collect popular romance as part of a larger popular culture collection or in their special collections, but those collections are, by definition, special and not always accessible to those who use the general collection. Furthermore, libraries may acquire romance as a subset of the general collection, specifically geared toward leisure reading for students and faculty rather than as material used for scholarly study (Dewan; Heish and Runner).

There are those librarians who advocate for buying best-sellers such as romance novels for research purposes in academic libraries because these works are a reflection of our culture and, if we do not collect and preserve them now, these materials may be lost forever (Sewell 450; Crawford and Harries 216; Moran 6; Hallyburton, Buchanan, and Carstens 109). A study conducted by Justine Alsop confirms that collecting contemporary popular fiction as part of the library’s general research collection has found increasing acceptance among English literature librarians (584), but this movement has a long way to go before it receives the mass acceptance needed for popular romance to be a significant part of academic library collections.

Several factors play into why popular romance may not be collected by university libraries. For example, librarians have variously claimed that popular culture materials: do not relate to their institutional mission, are delivered by public libraries, garner only transitory interest from patrons, place too high a demand on limited budgets, shelf space, and staff time, and are often printed in paperback format, which is a preservation nightmare (Sewell 453, 459; Van Fleet 71; Alsop 581-582; Hsieh and Runner 192-193; Odess-Harnish 56; Hallyburton, Buchanan, and Carstens 109).

Mass-market paperbacks are often printed on acidic paper that becomes yellow, brittle, and unusable over time. The options available for preserving these works, such as performing a deacidification process on the paper or reformatting the books by microfilming or digitizing, are all quite costly, especially considering the volume of romance novels printed per year. Pillete (2003) estimates that the cost for microfilming one book is $125 U.S. dollars, digitizing is $50 U.S. dollars per book, and neither of these methods does anything to preserve the original work. Deacidification, even if done in mass quantities, could still be as much as $16 U.S. dollars per average volume (Pillete 1-5). One might think that ebooks would be a viable solution, considering they are in their native digital format and solve many preservation and space-saving concerns; however, many older romance titles are not yet available in ebook format and the licensing agreements for ebooks with libraries can become a barrier to access, especially since there is no possibility of checking out an item to a researcher who is not a patron of the library that has licensed the ebook, as in the case of interlibrary loan.

Another reason for lack of collection in this area is that liaison librarians tend to depend on review sources to help make collection development decisions. Popular romance is not generally covered by standard review sources, and it becomes a self-perpetuating cycle. Review sources claim there are too many romance novels to possibly begin to review them all, and there is not enough space to deal with them on the pages of the review issues (Fialkoff 118). Consequently, librarians claim there is not enough space to handle romance novels in the stacks of the library, especially when librarians must ask themselves if this is the best use of the space they have. Is this what researchers are going to need or use the most? Is it the best way to spend a limited library budget, especially if they cannot even get reviews of these books in their normal sources to indicate the quality of the work?

This could be seen as a string of excuses, or prejudice against popular culture materials, or prejudice against popular romance, specifically. There has been an ongoing resistance to collecting popular materials in academic libraries, with these items viewed as a “disposable culture” not worthy of preserving (Hoppenstand 236), and libraries are slow to change to a new way of collecting (Sewell 453; Odess-Harnish 56). However, beyond any prejudice is the reality of romance publishing. According to the most recent statistics from the Romance Writers of America, romance makes up 13.2% of the consumer market and produces over 9,000 books per year (RWA, “Romance Literature Statistics: Industry Statistics”). Not only would collecting all of these works take up a lot of shelf space, but it would also require a library to invest a not insignificant amount of money into purchasing the books, and also preserving them. It is perhaps for this reason that even libraries that do collect popular romance materials often rely heavily, if not exclusively, on donations to grow their collections (Sewell 459; Flesch 121; Adkins et al. 63).

Where Should Popular Romance Materials be Shelved?

Despite the budgetary and spatial constraints, there are libraries that have impressive collections of popular culture materials, which may include popular romance. If a library acquires popular romance, a decision must then be made about where these materials should be housed within the library’s collections. The two usual options are a special collection, which can mean the main special collection of a library or a smaller subset, such as a popular culture special collection; or the general collection, which may indicate the library’s main stacks or a subset called a “browsing collection” or “leisure reading collection.” There are clear benefits and drawbacks to both special and general collections. The benefit of a special collection is that special collections librarians actively work to preserve their materials, and the drawback is that sometimes their finding aids may describe their collections, but not the individual items in that collection. If a patron is looking for a specific book, finding out if the library owns it can become an issue. Conversely, general collections usually provide full cataloguing for materials, but there is less concern for preservation. Any patron can check these materials out, not just researchers, and if these books are lost or damaged, they may not always be replaced.

Even within the main stacks of the general collections, it is often unclear where popular romance material will be shelved. The field of Popular Romance Studies is cross-disciplinary, as noted on the International Association for the Study of Popular Romance’s (IASPR) and the Journal of Popular Romance Studies’ (JPRS) websites. IASPR’s Mission page claims that the organization is “dedicated to fostering and promoting the scholarly exploration of all popular representations of romantic love,” and the JPRS’s About page adds that these representations may be in “popular media, now and in the past, from anywhere in the world.” This is an undeniably, and deliberately, broad definition for the field. The JPRS About page goes on to elaborates that

we welcome [ . . . ] contributions from all relevant disciplines, including African American / Black Diaspora Studies, Art, Communications, Comparative Literature, Cultural Studies, Education, English, Film Studies, History, LGBTQ Studies, Marketing, Philosophy, Psychology, Religious Studies, Sociology, Women’s and Gender Studies.

There is nothing wrong with a field having a broad scope, especially when the journal publishing these resources is online. However, libraries are physical buildings that are “highly organized systems which provide information which is, by and large, contained in print materials [ . . . ] that can be only in one place at a time” (Searing 7). Cataloguing materials for the general collection of most academic libraries in the United States involves using the subject headings from the Library of Congress Classification system. While multiple subject headings can be assigned to each work, only one can be primary, which then indicates where an item will be shelved. A small sampling of subject headings assigned to scholarly monographs in Popular Romance Studies include

Love stories — Appreciation.

Love stories, American — History and criticism.

Love stories, English — History and criticism.

American fiction — 20th century — History and criticism.

Authors and readers — United States.

Sex role in literature.

Popular literature — History and criticism.

Popular literature — English-speaking countries — History and criticism.

Women and literature — Australia — History — 20th century.

Women — Books and reading — United States.

Therefore, as with all interdisciplinary fields, even if a library does acquire popular romance, the materials will be scattered throughout the general collection, unless it is placed together in a special collection. There is no uniform approach to handling popular culture materials in academic libraries. How each library chooses to handle this issue is individual to the library and the group of librarians entrusted with managing the collection.

Popular Romance Scholarship Core Collection

While “academic libraries may collect mainstream fiction, it is more often the case that works about a particular author or novel [or film] will be included in the collection, while the specific works (primary sources) are unavailable except through interlibrary loan or a visit to a local public library” (Van Fleet 66). If this is the case, one might ask how likely it is for academic libraries to collect these secondary sources when they do not have a popular romance major or minor program? Secondary sources can also be primary sources, but for the sake of simplicity, this article is going to label secondary sources as those which analyze or examine popular romance for a scholarly audience.

Van Fleet’s statement again raises the issue of the need for a core collection. Which works define the absolute minimum that would be required to say a library had a core collection of romance scholarship? If popular romance scholars cannot define this, it will be difficult for a library unversed in popular romance to do so either. To begin the process of defining a core collection, and to find out how likely it is for those core works to be collected by academic libraries, this article will borrow from a list complied by Pamela Regis and posted on the RomanceScholar Listserv (see Appendix A). Also, the author of this article received a $1,000 U.S. New Faculty Fund to buy monographs for the library collection when hired in 2009 at San Jose State University in California. This fund was used to purchase popular romance scholarship, and a list of those purchases was compared to Pamela Regis’s list. The two lists compiled many of the same works, with the exception of approximately 10 titles (see Appendix B). Combined, these lists make up a rough estimate of the core collection in this area, which added up to 45 titles in total.

To gain an understanding of how likely it is for universities to collect popular romance scholarship, this article examines the two public university systems in California as a case study.

The California State University (CSU) system has 23 campuses, a full time undergraduate enrollment of almost 350,000 students, and an additional 49,000 graduate students. The CSUs are teaching institutions that offer Bachelors and Masters degrees. A few CSUs offer joint or gateway doctoral degrees and several campuses are in the process of opening doctoral programs in education, physical therapy, and nursing, but these programs are the exception rather than the rule (“CSU Term Enrollment Summary – Fall 2010”; “CSU Historic Milestones”).

The second system is the University of California (UC), which has 10 campuses with a full time undergraduate enrollment of approximately 180,000, and a graduate enrollment of 45,000. The percentage of graduate enrollment is much higher in this system because these are research institutions, offering doctoral studies for many of their major departments (“UC Statistical Summary of Students and Staff – Fall 2010”). It would seem logical that the UC campuses would have more romance scholarship in their collections because they have more money to spend on research materials, but with no major departments in the area, it did not seem likely that many of the core list items would appear in their collections.

In addition to examining the collections of California’s public university systems, this study also took an initial look at how many libraries worldwide owned the popular romance core works. This was accomplished by searching for each title in WorldCat, the largest catalog in the world, which indexes the holdings of about 72,000 libraries in 170 countries (“WorldCat Facts and Statistics”). All of the CSU and UC libraries are represented in WorldCat, so there was some cross over in the results.

For the UC libraries, a search for each popular romance core title was conducted in Melvyl, the union catalog for the UC system, which lists the holding for each edition and format of the volumes in those libraries. The union catalog for the CSU libraries was also searched for each title. It is important to note that this study was not weighted toward any specific edition or format. If a library held a first edition in hardcover in their collections, it would be counted equally with a library that held a third edition in ebook format, for example.

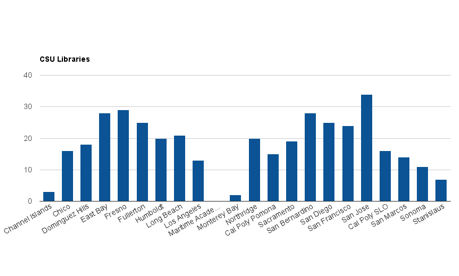

Fig. 1 displays the results for the search of the CSU libraries. Only one campus had none of the books on the list, but it was the California Maritime Academy, which focuses on educating those who want to join the merchant marines. The CSUs at Channel Islands and Monterey Bay are both the smallest and newest campuses, which would attribute to a smaller collection overall and thus lower numbers in this study (“CSU Term Enrollment Summary – Fall 2010”; “CSU Historic Milestones”).

Fig. 1 Number of core popular romance titles held by each CSU library.

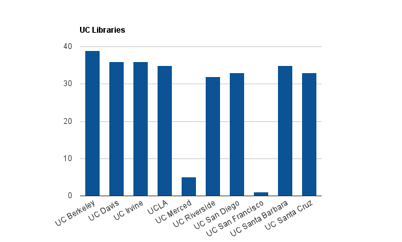

The results for the UC institutions are displayed in Fig. 2. Again, the newest and smallest campus at UC Merced returned low numbers, as well as UC San Francisco, which focuses heavily on medicine and the hard sciences and thus would be less likely to collect in an area such as Popular Romance Studies, which, despite its interdisciplinary nature, is still weighted toward social science and humanities disciplines.

Fig. 2 Number of core popular romance titles held by each UC library.

Overall, the CSU average was 17.4 of the 45 popular romance core titles, and the UC average was 28.5 titles. The highest collectors in the CSUs were San Jose with 34 titles, which can be attributed to the selections made with the author’s New Faculty Fund, Fresno with 29 titles, and a tie between East Bay and San Bernadino, each with 28 titles. There are two librarians at East Bay who have most likely contributed to the high number of core titles there. Doug Highsmith, who has published several times on the importance of collecting popular culture materials, and Kristin Ramsdell, who co-wrote an article called “Core Collections in Genre Studies: Romance Fiction 101” (Wyatt et al.). It is unclear, however, why San Bernadino or Frenso would rank above the other CSUs in this area.

The top three UC libraries were Berkeley with 39 of the core titles, and Davis and Irvine, each with 36 of the titles. Other than the fact that these are some of the largest UC campuses, there is no clear reason why they collected more popular romance scholarship than the other UCs. A key question is whether librarians specifically selected these titles for acquisition, or if they came into the library’s collections via an approval plan.

Many libraries do not make all of their acquisitions decisions. Instead, they subscribe to an approval plan through a book vendor, which sends a selection of books based on a profile of the library’s patrons. These approval plans can save libraries money both in staff time as well as through discounts from the vendors. However, the vendors often overlook smaller publishers in their approval plans; therefore, librarians need to fill in those gaps with individual title selection. If the popular romance titles became part of the library’s collections through an approval plan, it is possible the librarians, faculty, and staff on that campus had very little or nothing to do with those acquisitions. If they were individually selected titles, one has to wonder which librarian supported popular romance studies, or which major department she was gearing the selection toward. There are many questions still unanswered, and further research needs to be conducted in this area.

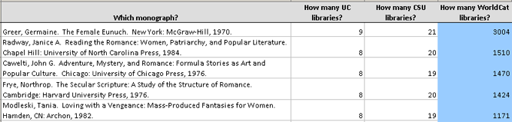

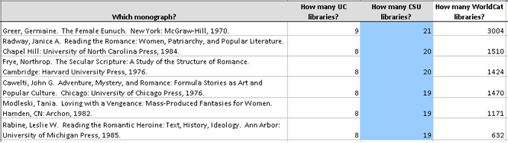

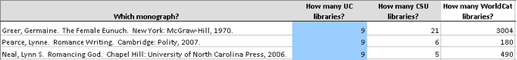

Regardless of how or why the titles became part of library collections, they are still available to the faculty and students of those campuses for research. Of the titles on the core list, which were the most likely to be collected, for whatever reason? This is a broader question than the CSU and UC systems, so it was important to include results from WorldCat as well. Fig. 3 shows the top five titles collected by libraries indexed in WorldCat. There are columns comparing how many UC or CSU libraries also collected these same titles. In WorldCat, Germaine Greer’s work was the most collected and was held in over 3,000 libraries. In the top five, Greer was followed by Janice Radway, John Cawelti, Northrop Frye, and Tania Modleski.

Fig. 3 Popular romance core titles held by the greatest number of libraries in WorldCat.

For the CSUs, we see the same titles, but in a slightly different order, with Frye jumping up from fourth to third. Cawelti, Modleski, and Leslie W. Rabine were in a three-way tie for the final spot. These numbers and their comparative UC and WorldCat rankings are displayed in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4 Popular romance core titles held by the greatest number of CSU libraries.

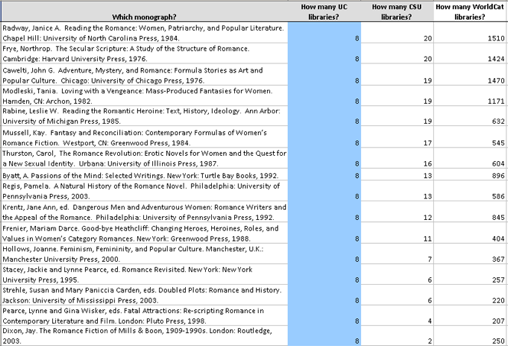

In the UC results displayed in Fig. 5, a few other titles rose to the top. Greer tied with Lynn Neal and Lynn Pearce as the most collected works in the UC system.

Fig. 5 Popular romance core titles held by the greatest number of UC libraries.

Interestingly, there were sixteen titles held by eight of the ten UC campuses, lending some credence to the idea that research universities are, on the whole, more likely to collect popular romance scholarship, despite the lack of a Popular Romance Studies program.

Fig. 6 Sixteen popular romance core titles held by eight UC libraries.

None of the UC or CSU libraries had a complete collection of the core list; however, only one title was not collected at all, and that was Beyond Heaving Bosoms: The Smart Bitches’ Guide to Romance Novels by Sarah Wendell and Candy Tan. One might speculate that this book would be considered the least “academic” of the works listed, and was thus overlooked by academic librarians and not included in approval plans for these university libraries.

Conclusion

There are several recommendations for popular romance scholars that can be given based on the information presented in this article. The first is that, if popular romance scholars want libraries to collect their core list of titles, especially with the vast amount of primary source material produced each year, they need to have a list of core titles. Librarians rely on review sources to help them choose which titles to select, and the review sources neglect popular romance materials. To fill this gap, it is recommended that IASPR put together a committee to compile a true core list of primary and secondary titles for popular romance studies. This list would need to be updated annually to include new titles.

As demonstrated by the comparison of research institutions, the UCs; and teaching intuitions, the CSUs; it is much more likely for research institutions to have the fiscal ability to collect new materials. Therefore, it would seem the best way to have an academic library dedicate the funds towards collecting popular romance materials would be to have a university—preferably a research level, doctoral granting institution—with a major department for Popular Romance Studies. How likely or how soon that is to happen is unknown, but it is a goal romance scholars should continue to strive for.

While it is possible for an academic library to collect every scholarly work on the popular romance core list, it would be an overwhelming expense for any one library to acquire a comprehensive collection of every primary source in popular romance studies. Therefore, a final recommendation would be to identify several libraries interested in collecting in this area and focus on a coordinated collection development effort at a national, regional, or consortial level in order to spread the cost and ensure a broader coverage of materials. In this way, romance scholars can ensure every primary and secondary core title is held and preserved by at least one library, and that there is no danger of losing valuable research materials forever, which, in the case of romance novels printed on acidic paper, becomes ever more likely with each year that passes.

Works Cited

“About.” JPRS.org. Journal of Popular Romance Studies, n.d. Web. 14 June 2011. <http://www.jprstudiestest.dreamhosters.com/about>

“About the Romance Genre.” RWA.org. Romance Writers of America, 2012. Web. 11 June 2012. <http://www.rwa.org/cs/the_romance_genre>

Adkins, Denise, Linda Esser, Diane Velasquez, and Heather L. Hill. “Romance Novels in American Public Libraries: A Study of Collection Development Practices.” Library Collections, Acquisitions, and Technical Services 32.2 (2008): 59-67. Science Direct. Web. 18 Sept. 2010.

Alabaster, Carol. Developing an Outstanding Core Collection. 2nd ed. Chicago: American Library Association, 2010. Print.

Bowring, Joanna. “And then he kissed her. . . ” Library & Information Update 7.6 (2008): 35-37. Library, Information Science & Technology Abstracts with Full Text. EBSCO. Web. 28 May 2011.

Crawford, Gregory A., and Matthew Harris. “Best-sellers in Academic Libraries.” College & Research Libraries 62.3 (2001): 216-225. WilsonWeb. Web. 26 May 2011

“CSU Historic Milestones.” Public Affairs. CalState.edu. The California State University, 2011. Web. 25 July 2011. <http://www.calstate.edu/PA/info/milestones.shtml>

“CSU Term Enrollment Summary – Fall 2010.” Analytic Studies Statistical Reports. CalState.edu. The California State University, 2011. Web. 21 May 2011. <http://www.calstate.edu/as/stat_reports/2010-2011/f10_01.htm>

Dewan, Pauline. “Why Your Academic Library Needs a Popular Reading Collection Now More Than Ever.” College & Undergraduate Libraries 17.1 (2010): 44-64. Library, Information Science & Technology Abstracts with Full Text. EBSCO. Web. 28 May 2011.

Fialkoff, Francine. “Romancing the Patron.” Library Journal 117.21 (1992): 118. Library, Information Science & Technology Abstracts with Full Text. Web. 28 May 2011.

Flesch, Juliet. “Not Just Housewives and Old Maids.” Collection Building 16.3 (1997): 119-124. Emerald Managment Xtra. Web. 23 February 2011.

Gabriel, Michael R. Collection Development and Evaluation: A Sourcebook. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow, 1995. Print.

Hallyburton, Ann W., Heidi E. Buchanan, and Timothy V. Carstens. “Serving the Whole Person: Popular Materials in Academic Libraries.” Collection Building 30.2 (2011): 109-112. Emerald. Web. 5 April 2011.

Hsieh, Cynthia, and Rhonelle Runner. “Textbooks, Leisure Reading, and the Academic Library. Library Collections, Acquisitions, and Technical Services 29.2 (2005): 192-204. Science Direct. Web. 28 April 2011.

Hoppenstand, Gary. “Editorial: Collecting Popular Culture.” Journal of Popular Culture 38.2 (2004): 235-238. Academic Search Premier. Web. 7 July 2011.

Johnson, Peggy. Fundamentals of Collection Development and Management. Chicago: American Library Association, 2004. Print.

Lee, Hur-Li. “What is a collection?” Journal of the American Society for Information Science 51 (2000): 1106-1113. Wiley. Web. 26 May 2011.

“Mission.” IASPR.org. International Association for the Study of Popular Romance, n.d. Web. 14 June 2011. <http://iaspr.org/about/mission>

Moran, Barbara B. “Going Against the Grain: A Rationale for the Collection of Popular Materials in Academic Libraries.” Popular Culture and Acquisitions. Ed. Allen Ellis. New York: Hawthorn, 1992. Print.

“Nora Roberts Foundation Gives McDaniel $100,000 for Research, Course Development.” McDaniel.edu. McDaniel College News & Events, 1 June 2011. Web. 2 June 2011. < http://www.mcdaniel.edu/11662.htm>

Odess-Harnish, Kerri. “Making Sense of Leased Popular Literature Collections.” Collection Management 27.2 (2002): 55-74. InformaWorld. Web. 7 July 2011.

Overcash, Gina R. “An Unsuitable Job for a Librarian? Collection Development of Mystery and Detective Fiction in Academic Libraries.” The Acquisitions Librarian 4.8 (1993): 69-89. InformaWorld. Web. 28 April 2011.

Pillete, Roberta. “Mass Deacidification: A Preservation Option for Libraries.” World Library and Information Congress: 69th IFLA General Conference and Council. 1-9 August 2003, Berlin, Germany. Web. 7 July 2011. < http://archive.ifla.org/IV/ifla69/papers/030e-Pilette.pdf >

Regis, Pamela. “Canonical Works in Romance Studies.” RomanceScholar Listserv Online Posting. RomanceScholar, 17 May 2011. Web. 18 May 2011.

“Romance Genres.” RomanceAustralia.com. Romance Writers of Australia, 2012. Web. 11 June 2012. <http://www.romanceaustralia.com/romgenres.html>

“Romance Literature Statistics: Industry Statistics.” RWA.org. Romance Writers of America, 2009. Web. 6 June 2011. <http://www.rwa.org/cs/the_romance_genre/romance_literature_statistics/industry_statistics>

Searing, Susan E. “How Libraries Cope with Interdisciplinarity: The Case of Women’s Studies.” Issues in Integrative Studies 10 (1992): 7-25. Web. 12 May 2011.

Seeman, Corey. “Collecting and Managing Popular Culture Material.” Collection Management 27:2 (2003): 3-21. InformaWorld. 28 April 2011. Print.

Sewell, Robert G. “Trash or Treasure? Pop Fiction in Academic and Research Libraries.” College & Research Libraries 45:6 (1984): 450-461. Web. 12 May 2011.

“UC Statistical Summary of Students and Staff – Fall 2010.” Statistical Summary and Data on UC Students, Faculty, and Staff. UCOP.edu. University of California Office of the President, 2011. Web. 21 May 2011. <http://www.ucop.edu/ucophome/uwnews/stat/statsum/fall2010/statsumm2010.pdf>

Van Fleet, Connie. “Popular Fiction Collections in Academic and Public Libraries.” Acquisitions Librarian 15.29 (2003): 63-85. Library, Information Science & Technology Abstracts with Full Text. EBSCO. Web. 28 May 2011.

“What is Romantic Fiction?” RNA-UK.org. Romantic Novelists Association, 2012. Web. 11 June 2012. <http://www.romanticnovelistsassociation.org/index.php/about/what_is_romantic_fiction>

“WorldCat Facts and Statistics.” OCLC.org. Online Computer Library Center, 2011. Web. 23 May 2011. <http://www.oclc.org/ca/en/worldcat/statistics/default.htm>

Wyatt, Neal, Georgine Olson, Kristin Ramsdell, Joyce Saricks, and Lynne Welch. “Core Collections in Genre Studies: Romance Fiction 101.” Reference & User Services Quarterly 47.2 (2007): 120-125. Library, Information Science & Technology Abstracts with Full Text. EBSCO. Web. 18 Sept. 2010.

Appendix A

Anderson, Rachel. The Purple Heart-Throbs: The Sub-literature of Love. London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1974.

Belsey, Catherine. Desire: Love Stories in Western Culture. Cambridge, Mass: Blackwell, 1994.

Betz, Phyllis M. Lesbian Romance Novels: A History and Critical Analysis. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2009.

Cadogan, Mary. And Then Their Hearts Stood Still: An Exuberant Look at Romantic Fiction Past and Present. London: McMillan, 1994.

Cawelti, John G. Adventure, Mystery, and Romance: Formula Stories as Art and Popular Culture. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1976.

Cohn, Jan. Romance and the Erotics of Property: Mass-Market Fiction for Women. Durham: Duke University Press, 1988.

Cranny-Francis, Anne. Feminist Fiction: Feminist Uses of Generic Fiction. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1990.

Dixon, jay. The Romance Fiction of Mills & Boon, 1909-1990s. London: Routledge, 2003.

Flesch, Juliet. From Australia with Love: The History of Australian Popular Romance Novels. Fremantle, WA: Curtin University Books, 2004.

Fletcher, Lisa. Historical Romance Fiction: Heterosexuality and Performativity. Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2008.

Frenier, Mariam Darce. Good-bye Heathcliff: Changing Heroes, Heroines, Roles, and Values in Women’s Category Romances. New York: Greenwood Press, 1988.

Frye, Northrop. The Secular Scripture: A Study of the Structure of Romance. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1976.

Goade, Sally, ed. Empowerment versus Oppression: Twenty First Century Views of Popular Romance Novels. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2007.

Greer, Germaine. The Female Eunuch. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1970.

Grescoe, Paul. The Merchants of Venus: Inside Harlequin and the Empire of Romance. Vancouver: Raincoast, 1996.

Kaler, Anne K. and Rosemary Johnson-Kurek, eds. Romantic Conventions. Bowling Green, OH: Bowling Green State University Popular Press, 1999.

Krentz, Jane Ann, ed. Dangerous Men and Adventurous Women: Romance Writers and the Appeal of the Romance. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1992.

Mann, Peter H. A New Survey: The Facts About Romantic Fiction. London: Mills & Boon, 1974.

Mann, Peter H. The Romantic Novel: A Survey of Reading Habits. London: Mills & Boon, 1969.

McAleer, Joseph. Passion’s Fortune: The Story of Mills and Boon. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Modleski, Tania. Loving with a Vengeance: Mass-Produced Fantasies for Women. Hamden, CN: Archon, 1982.

Jensen, Margaret Ann. Love’s $weet Return: The Harlequin Story. Bowling Green, OH: Bowling State University Popular Press, 1984.

Mussell, Kay, ed. “Where’s Love Gone?: Transformations in the Romance Genre.” Paradoxa Vol. 3, No. 1-2. Vashon Island, WA: Delta Production, 1997.

Mussell, Kay. Fantasy and Reconciliation: Contemporary Formulas of Women’s Romance Fiction. Westport, CN: Greenwood Press, 1984.

Neal, Lynn S. Romancing God. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006.

Paizis, George. Love and the Novel: The Poetics and Politics of Romantic Fiction. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 1998.

Pearce, Lynne and Gina Wisker, eds. Fatal Attractions: Re-scripting Romance in Contemporary Literature and Film. London: Pluto Press, 1998.

Pearce, Lynne. Romance Writing. Cambridge: Polity, 2007.

Rabine, Leslie W. Reading the Romantic Heroine: Text, History, Ideology. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1985.

Radford, Jean, ed. The Progress of Romance: The Politics of Popular Fiction. New York: Routledge, 1986.

Radway, Janice A. Reading the Romance: Women, Patriarchy, and Popular Literature. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1984.

Regis, Pamela. A Natural History of the Romance Novel. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2003.

Ross, Deborah. The Excellence of Falsehood: Romance, Realism, and Women’s Contribution to the Novel. Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 1991.

Stacey, Jackie and Lynne Pearce, ed. Romance Revisited. New York: New York University Press, 1995.

Strehle, Susan and Mary Paniccia Carden, eds. Doubled Plots: Romance and History. Jackson: University of Mississippi Press, 2003.

Thurston, Carol. The Romance Revolution: Erotic Novels for Women and the Quest for a New Sexual Identity. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1987.

Wendell, Sarah and Candy Tan. Beyond Heaving Bosoms: The Smart Bitches’ Guide to Romance Novels. New York: Fireside/Simon & Schuster, 2009.

Appendix B

Byatt, Antonia. Passions of the Mind: Selected Writings. New York: Turtle Bay Books, 1992.

Carr, Helen, ed. From My Guy to Sci-fi: Genre and Women’s Writing in the Postmodern World. London: Pandora Press, 1989.

Frantz, Sarah S.G., and Katharina Rennhak, eds. Women Constructing Men: Female Novelists and Their Male Characters, 1750-2000. Lanham: Lexington Books, 2010.

Hollows, Joanne. Feminism, Femininity, and Popular Culture. Manchester, U.K.: Manchester University Press, 2000.

McKnight-Trontz, Jennifer. The Look of Love: The Art of the Romance Novel. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2002.

Salmon, Catherine, and Donald Symons. Warrior Lovers: Erotic Fiction, Evolution and Female Sexuality. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003.

Schurman, Lydia Cushman, and Deidre Johnson, eds. Scorned Literature: Essays on the History and Criticism of Popular Mass-produced Fiction in America. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 2002.

Watson, Daphne. Their Own Worst Enemies: Women Writers of Women’s Fiction. London: Pluto Press, 1994.

1 “Popular romance” can also be referred to as “romantic fiction,” and either term can include works that do not have a happily-ever-after ending. Although novels are not the only medium for popular romance/romantic fiction, this article relies on definitions provided by romance author organizations such as the Romance Writers of America, the Romance Writers of Australia, and the UK’s Romantic Novelists’ Association for its definition of popular romance/romance fiction. While the Romantic Novelists’ Association sidesteps a true definition, it does call for a love story within the scope of the work (“What is Romantic Fiction?”). Both of the other organizations’ basic definition of romance includes works that have a central focus on a love story with an emotionally satisfying and optimistic ending (“About the Romance Genre”; “Romance Genres”). This article prefers the narrower parameters offered by America and Australia, but embraces the idea that popular romance/romantic fiction need not conclude with the traditional happily-ever-after.