Introduction

[End Page 1] Critical analysis of the romance novel, so far, has mainly focused on gender politics. One of the few clusters of texts of critical discourse on the genre that, in a sustained manner, take into consideration the intertwined issues of gender, ethnicity and politics, paying due attention to the taxonomy of cultural and ethical values grounding this category of works, is scholarly criticism of ‘desert novels’ in relation to their depiction of Middle Eastern cultures before and after 9/11.[1]

In her essay on this topic, Amira Jarmakani argues that “the conflation of dark and dangerous […] signif[ies] a conflation between race and violence,” that, she argues, “can be seen in the romance genre as a whole” (896), not only in the portrayal of mysterious and broody sheiks. She continues by explaining how traits perceived as exotic are employed by authors to add to the virility of the hero:

Because the most common type of hero is the alpha male – that is a strong, hard, dominant and/or aggressive, confident man with a tender spot that the heroine uncovers – authors sometimes use exotic tropes to give the hero his hard edges. In constructing the figure of the Latin lover, for instance, authors can mobilize mainstream assumptions about machismo to signify alpha maleness. (896)

Jarmakani does not return, in the course of her study, to the topic of the literary construction of the Latin lover. As I wish to do so, I propose the term ‘Mediterranean Man’ for the figure of the ‘Latin lover,’ a term which seems to be more appropriate precisely because it suggests a conflation of the Southern European with the Arab man. In this essay, I will argue that Harlequin short contemporaries constitute a literary category in which mainstream assumptions about Southern European machismo often overlap with common Western stereotypes of Middle Eastern cultures. This is not due to concrete affinities between the two worlds, but to their perceived shared discontinuity with the (post)modern world, their alleged closeness to traditional values (family, religion, a more rigid adherence to gender roles), and, at times, their endorsement of those ethical standards supposed to be found at the opposite spectrum of a modern, secular, and equal society.

Jarmakani points out that whereas descriptions of the physical appearance of Arab men in desert novels until recently used to abound in fascinated and fascinating remarks on the colour of their skin, in the course of the last decade such accounts have become increasingly rare. This is due, she maintains, to the controversial nature of issues connected to representing ethnic groups that have been, for the last twenty years or so, at the centre of social life and political debate in Anglo-America. Since such contentious concerns are [End Page 2] largely absent when dealing with Italy, the fascination of the genre with exotic skin tones can still be freely and joyously expressed.

Therefore, in ‘desert novels,’ descriptions such as the ones we find in Delaney’s Desert Sheikh by Brenda Jackson (2001) – in which the heroine Delaney remarks on the “rich-caramel coloring of his [the sheik’s] skin, giving true meaning to the description of tall, dark, and handsome” (Jackson 2001, reported in Jarmakani 900), and in which, imagining a future son with the Sheik, she fantasizes about his “dark, copper-coloured skin, head of jet-black curls, and dark chocolate colored eyes” (Jackson 2001, reported in Jarmakani 900) – are increasingly infrequent. In contrast, in ‘Italian themed novels’ the Mediterranean Man is still very much the object of a comparable kind of statements:

Vying for first place with his lips were his eyes. Deep chocolate-brown, they were set off by the requisite thick, long lashes. But the chocolate didn’t have the dull, matte quality of a solid block. It was warm and glossy and liquid, the dark variety – there was no diluting milky sweetness. And, at the very centre, there was a hardness – a ‘don’t go there’ dangerous quality that totally aroused the curiosity of Pandora in Emily. It was like the bitterness at the bottom of a strong coffee or the darkest of dark chocolate that her taste buds both desired and recoiled from. (Anderson, Between the Italian’s Sheets loc 87)

This passage touches upon several of the discursive patterns that will be discussed in this essay: a scopophiliac approach to the description of the Mediterranean Man; a fascination with darkness and its opposition to whiteness (diluting milky sweetness) perceived as safe and dull; the conflation of darkness with erotic allure and danger; and the mechanism of attraction/rejection towards the other.

In A Natural History of the Romance Novel (2003), Pamela Regis defines short contemporary romance novels as “narrow romance formula” (28) works that concentrate all the narrative elements that usually characterize a romance story and that compress all its drama within a limited number of pages. Regis explains the great popularity this particular subgenre has enjoyed in the course of the twentieth century and the founding and history of the main publishing houses (Mills & Boon, Harlequin, and Silhouette) associated with the category. Lastly, she gives a brief account of their different declensions:

Lines vary in length, in the presence and kind of sex, the presence or absence of a suspense plot, in their chronological setting (for example, Regencies) or their photographic setting (for example, Westerns) and other elements that some readers look for in a romance novel. (157)

Although among the current ‘lines,’ or series, of short contemporaries (for Harlequin: Dare, Intrigue, Medical, Inspired, Nocturne, among others) there is not one which is specifically ‘Italian themed,’ a simple keyword-search on the Harlequin website will generate a large number of ‘Italian’ titles appearing across the different series: The Italian’s Pregnant Mistress; The Italian Tycoon’s Bride; Sicilian Husband, Blackmailed Bride; Untamed Italian, Blackmailed Innocent; The Italian’s Virgin Acquisition; The Italian’s Vengeful Seduction, and so on. [End Page 3]

In this paper, I will discuss instances of the representation of Italian heroes based on a complex combination of notions of gender, ethnicity, nationality, and culture. The focus is on the construction of national otherness, even if this is inscribed, I fully recognize, within the (more relevant to the genre) frame of gender politics. My main argument is that however crass and/or formulaic (reduced to a few basic components) the construction of the Italian male is, it is still the result of the complex history of the perception of Italy and Italians by northern Europeans, and an instance of the current taxonomic arrangement of cultures that has been developing over the course of the modern centuries. In short, the question I wish to ask is: what happens when the hero is represented (and objectified) not only as male, but as male and Italian?

More specifically, expanding on Elizabeth Gargano’s appraisal of The Sheik, a novel featuring strong and contradicting patterns of attraction to and rejection of an orientalised male, as a text which “explores insecurities and doubts at the heart of the British imperial pride and self-sufficiency – a generalized fear that power and potency have been lost along with the ‘animal passions’” (184-85), I would like to put forward the hypothesis that the figure of the Italian hero/Mediterranean Man, constructed along the coordinates of a primal exoticism, offers the opportunity to momentarily re-appropriate such passions without having to deal with the contentious issues associated with the politics of otherizing Middle Eastern cultures.

I will demonstrate that, within the limits of this particular sub-category of the romance novel, a peculiar creation of national identity is actualized, one based on an understanding of identity as ethnicity, and of national character as genetic and innate. The depiction of the exotic character of the Italian male is carried out through an almost mantra-like reiteration of immediately detectable physical traits that mainly belong to the domain of ‘darkness,’ a quality attributed to the physical features (skin, hair, eyes, eyelashes, beards) as well as ‘immaterial’ elements (voice, accent, moods, feelings) characterizing Italian heroes, a darkness perceived as generally foreign but especially alien to the Anglo-Saxon male, who is portrayed as normative, as well as to the heroine.[2] This essay analyses twenty short contemporaries written between 2000 and 2017 that have been reprinted in the course of the last five years (2014-2018). Interestingly, several of the authors who have penned the novels under scrutiny – Maisey Yates, Kate Walker, Michelle Reid, Kate Hewitt, and Lynne Graham – have also engaged with the category of the desert/sheik novel.

Olive Skin, Chocolate Eyes

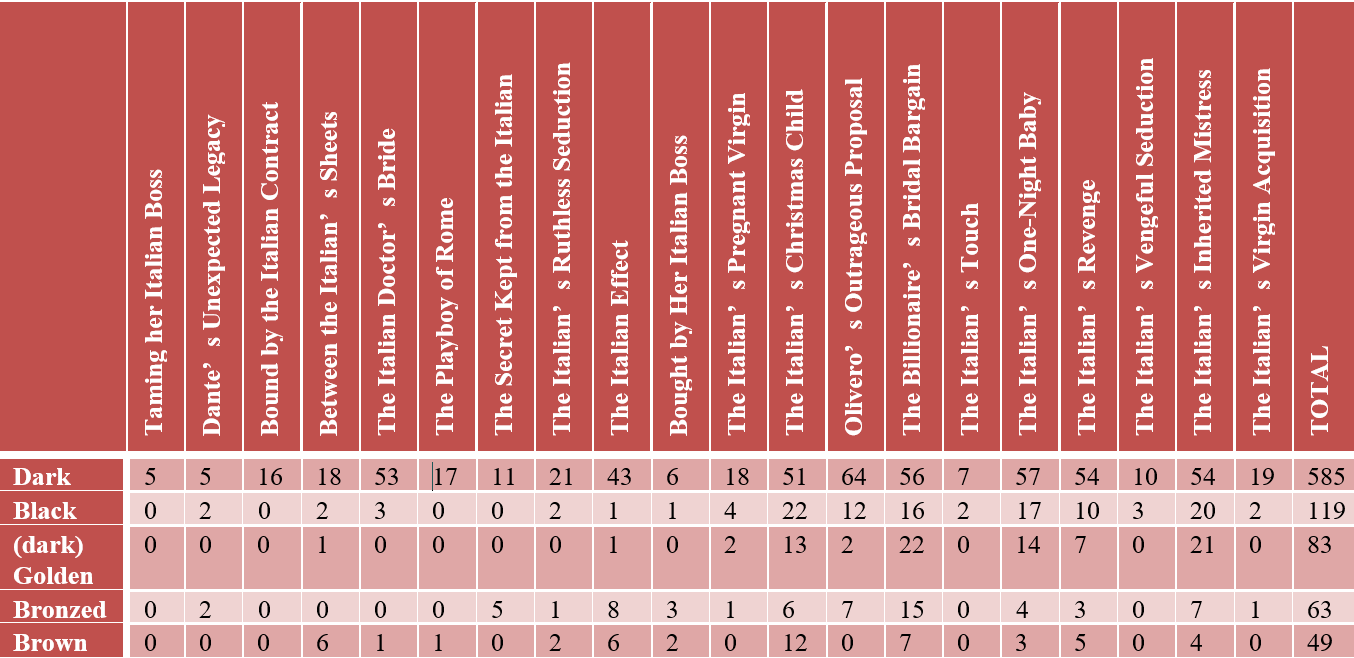

In this segment of the essay, I will focus on and isolate a cluster of recurring descriptive patterns employed in defining Italian masculinity in Harlequin short contemporaries. There is a sustained reiteration, within the genre, of the darkness of the skin, eyes and hair of the Italian hero/Mediterranean man. A constellation of terms is repeatedly employed in a variety of recurring combinations: “dark gaze,” “dark eyes,” “dark golden eyes,” “dark golden gaze,” “olive-toned skin,” “bronzed skin”. The table at the end of this section presents and summarizes the use of some of the most commonly used adjectives. Often the Italian hero is compared to paintings or sculptures of the classic [End Page 4] tradition, and often, through the heroine’s eyes, the author presents the reader with a ‘panoramic’ view of the hero’s body which exemplifies an eminently scopophiliac approach to it. Such descriptive patterns do not only apply to the Italian hero, but to the southern (Mediterranean) hero in general. As María Pérez-Gil observes in her article on British constructions of Spanish masculinity in the romance novel during the 1970s:

Darkness marks the Latin hero out as different through an iterative rhetoric that exoticizes, eroticizes, and others him. While frequent references to his dark hair, black eyes, and olive skin are intended to heighten his exoticism and virility, these elements also accentuate the cultural and ethnic differences that separate him from the heroine, whose English rose complexion and clear eyes are a national marker or metonymy of her Englishness. Her whiteness and the darkness of southern Europeans metaphorize the differences between the white north and the dark south, with all their accompanying cultural, gender, and ethnic imaginaries. (5)

I will return to this study as it effectively isolates an analogous set of tropes and descriptive patterns to the ones described in the present article. Although Pérez-Gil’s article focuses on a different historical phase of the genre, I believe and will try to demonstrate that the ‘exoticizing rhetoric’ which accompanies the portrayal of Mediterranean Men has survived to the present day.

The Hero’s Darkness

In Between the Italian’s Sheets by Natalie Anderson (2009), Luca and Emily meet at an opera performance. Emily is immediately attracted to extraordinarily good-looking Luca:

He was tall, he was dark, he was handsome. So far, so cliché. Like almost every man she’d seen in this city [Verona] he was immaculately groomed, but there was so much more. There was the strong, angled jaw and the faint shadow of stubble. (loc 83)

In the text and, indeed, throughout the genre, references to the hero’s dark eyes and complexion are recurring: “dazed, she studied the difference in their colouring. She had come from a cold winter so her skin was pale, whereas his olive complexion had been enhanced in the heat of the European summer” (loc 535); “she stared hard into the darkness of his eyes, let hers roam over his features, his olive skin, the angled jaw that right now was shadowed with stubble, the full mouth” (loc 735). The analogy of Luca’s darker skin with chocolate (inviting and tempting, and a quintessentially hedonistic food) is frequently employed throughout the novel.

In The Billionaire’s Bridal Bargain by Lynne Graham (2015), the Mediterranean Man, Cesare, is a wealthy, authoritative businessman particularly attached to his grandmother. Cesare is described as “simply…stunning from his luxuriant black hair to his dark-as-bitter- [End Page 5] chocolate deep-set eyes and strong, uncompromisingly masculine jawline” (loc 234, emphasis in original); “Tall, darkly handsome male” (loc 574); “he was truly beautiful, sleek and dark, exotic and compellingly male” (loc 1381). Cesare has “lean, darkly handsome features” (loc 641); a “lean, darkly handsome face” (loc 392); “beautiful dark golden eyes” (loc 403); a “lean bronzed face” (loc 641, 836, 892); and “brilliant dark eyes as hard as jet” (loc 685).

In The Playboy of Rome (2015) by Jennifer Faye, Dante, the Italian hero, is described as “dark and undeniably handsome” (loc 127), with “tanned skin around his dark eyes” (loc 134). The eyes, in particular, are “dark and mysterious” (loc 189), and the expression “dark gaze” is very frequently used (loc 189, 270, 1495, 1706). In The Italian’s Christmas Child (2016) by Lynne Graham, the expression “dark golden eyes” is persistently repeated (loc 544, 576, 727, 1038, 1194, 1486, 1630, 1658, 2060, 2155), and Vito, the male protagonist, is a “glorious display of bronzed perfection” (loc 695).

In The Italian Doctor’s Bride by Margaret McDonagh (2006), the Italian hero is a handsome and compassionate physician who helps healing the heroine of a past trauma through understanding and sympathy. The dark and exotic quality of his physical traits gives his appearance a peculiarly alluring but unsettling appeal:

She felt distinctly on edge. As he came closer, she could see he was incredibly good-looking in a rugged and dangerous kind of way, his raven-black hair short but thick, his dark eyes watchful as his disturbing gaze raked over her. (loc 238)

Recurring expressions in the novel focus on “olive-toned skin” (loc 1053, 1739, 2287) and “chocolate eyes”: “He had the kind of eyelashes many women paid good money to fake. They were long and lustrous, fringing eyes the colour of rich, melted chocolate, warm and tempting” (loc 519), “smouldering dark eyes” (loc 244, 1752), “molten eyes” (loc 1514, 2351), “dark eyes” (loc 240, 244, 346, 412, 830, 939, 1206, 1495, 1587, 1594, 1752, 1771, 1838, 2064, 2105, 21, 53, 2185, 2256, 2351, 2484, 2592, 2610), “dark gaze” (loc 358, 420, 742, 774, 950, 1004, 1012, 1119, 1206, 1616, 2360), “dark, sultry eyes” (loc 1745, 2308), “dark and compelling gaze” (loc 1787), “olive-toned flesh” (loc 1864), “olive-toned hand” (loc 804).

The Italian Hero as a Work of Art

In Catherine George’s Dante’s Unexpected Legacy (2014), Dante is an elegant Italian winemaker. Extremely attached to his family and, in particular, to his deceased grandmother, he is a successful, imposing but compassionate businessman. Throughout the story, ‘Italy’ is merely a signifier for beautiful villas, picturesque landscapes and expensive wine; it is a term summoned to evoke a series of static images, not to describe a dynamic setting. Pérez-Gil observes that:

In British romance novels, Spain is often the land of the flamenco, the castanets, bullfighting, the fiesta, the siesta, and a blazing sun. References to [End Page 6] the political situation […] are generally absent from the novels, except if we read them in between the lines. For, unlike Britain, Spain is depicted as a ‘still’ country that remains stuck in traditions and lethargic motionlessness. (6)

Precisely the same could be said of Italy, which is often described as a timeless land of continuous traditions: long and unbroken family histories, winemaking, the aperitivo, the pasta, the siesta, and a blazing sun. Within the context of romance novels, Italian men in particular get often inscribed within this framework of perceived timelessness and unbroken traditions as recurring instantiations of archetypes of ‘Southern beauty,’ cyclically presenting the same physical features as well-known figures and characters of the classic Italian tradition of painting and sculpture.[3]

Dante is exotic and endearingly foreign (he does not know how to make tea!). His beauty is described in terms of an alluring darkness and affinity with classic works of art: “To hide her horrified reaction, she turned very slowly to confront a tall, slim man with dark curling hair and a face that could be straight out of a Raphael portrait” (George, loc 118). “Rose melted against him, luxuriating in contact with the lean, muscular body that to her eyes could have been a model for one of the sculptures she’d seen in Florence” (George, loc 2412).[4]

The Scopophiliac Approach to the Male Hero

The scopophiliac instinct is defined by Laura Mulvey in her seminal essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” (1975) as the pleasure in looking at another person as an erotic object. “In a world ordered by sexual imbalance,” she argues

Pleasure in looking has been split between active/male and passive/female. The determining male gaze projects its fantasy on to the female figure which is styled accordingly. In their traditional exhibitionist role women are simultaneously looked at and displayed, with their appearance coded for strong visual and erotic impact so that they can be said to connote to-be-looked-at-ness. Woman displayed as sexual object is the leit-motif of erotic spectacle […] she holds the look, plays to and signifies male desire. (837)

Romance novels in general and mass-market short contemporaries in particular constitute one of the (perhaps increasingly less) rare contexts in which this mechanism is reversed: the genre abounds in scopophiliac descriptions of the male body. For instance, in the already mentioned The Italian Doctor’s Bride, there are numerous ‘panoramic views’ of Nic’s body: “olive-toned skin drawn over muscle, a light dusting of dark hair, tapering from his chest down his abdomen to the unfastened waistband of his jeans, broad shoulders, his dark hair still damp from the shower” (McDonagh, loc 1739).

In The Italian’s Touch by Carol Marinelli (2015), a widowed nurse goes back to work after a long time. She meets a handsome Italian doctor, Mario, tough and commanding at work but sweet and helpful in private. The heroine, Fleur, makes frequent remarks such as [End Page 7] the following one: “something must have got under that gorgeous olive skin of his” (loc 282). She frequently enjoys panoramic views of Mario’s body which, once again, reiterate the hero’s exotically dark traits: “The angle allowed her more than a glimpse of Mario, and Fleur drank it all in – the strong features, the long straight nose, thick dark eyebrows and even thicker eyelashes” (loc 795). Or: “Fleur ran her eyes over every inch of him, and he was as wondrous as she’d imagined – only more somehow. The ebon hair that matted his chest, thick yet soft, his nipples as dark as mahogany stiffening under her touch” (loc 1664).

Adjectives of Darkness

The table below illustrates the recurrence of some of the most popular adjectives employed, across the 20 novels, to describe the Italian character’s colour of skin, hair, eyes, brows and eyelashes. Often the same adjectives, especially ‘dark,’ are used to define immaterial traits, such as the hero’s accent, voice, mood and feelings (“dark voice,” “dark accent,” “dark satisfaction,” “dark passion”).

The Italian male hero awakes the curiosity of the heroine and her erotic interest at the same time as he re-activates, through the ‘darkness’ of his appearance, a well-known mechanism of attraction to and fear of the other that is reminiscent of the psychological dynamics explored by postcolonial critical writings, and, within this specific literary context, critical writings of the desert novel. Pérez-Gil describes this mechanism as follows:

The Italian male hero awakes the curiosity of the heroine and her erotic interest at the same time as he re-activates, through the ‘darkness’ of his appearance, a well-known mechanism of attraction to and fear of the other that is reminiscent of the psychological dynamics explored by postcolonial critical writings, and, within this specific literary context, critical writings of the desert novel. Pérez-Gil describes this mechanism as follows:

In romance fiction, the darkness of southern European men is something erotically gratifying and culturally terrifying. This rhetoric reproduces the [End Page 8] cultural and colonial geography that splits northern and southern Europe. Because of the south’s alleged primitiveness, the masculinity of its men is prefigured as naturally instinctive and virile. (5)

I merely wish to add to this that the reiteration of the separation between Northern and Southern Europe mainly carries its own peculiar shade of ambiguity, a more diluted form of it, perhaps a step removed from anxiety and fear, and closer to a purely hedonistic appreciation of the exotic qualities of the Mediterranean Man.

A ‘Mediterranean’ DNA

In romance novels, such exotic qualities are presented as natural and inborn. They are the result not so much of a social and cultural environment, but of genetic characteristics. Therefore, there occurs a ‘distancing’ of the Italian hero from a normative kind of (white and British) maleness constructed and articulated on the grounds of a perceived otherness conflating race, nationality and culture into one and the same exotic cocktail. Therefore, in Taming Her Italian Boss by Fiona Harper (2014), for instance, the hero, Max, successful, blasé and uncommitted, hides ‘true Italian-ness’ (evidently a ‘genetic essence’ he carries in his blood), under a veneer of cold rationality:

She had thought him a robot, a machine, but […] there was a lot more inside there than met the eye, maybe even a man with true Italian blood coursing through his veins, a man capable of revenge and passion and utter, utter devotion. (loc 830)

In this specific category, Italian men are often portrayed as carrying a sort of ‘Mediterranean DNA’ that accounts for their essential traits.

Within the well-known frame of the uncommitted, authoritative and arrogant male hero, some other specifically ‘Italian’ traits are accommodated: the Italian male, often (but not always) at the centre of a large, boisterous and tightly-knit family, is especially proud, vengeful, values family and family traditions, and he is affected by them in a way in which Anglo-American heroes seldom are. His ‘Mediterranean’ DNA sets him apart from white normativity, relegating him to a world where the natural and genetic orders rule over self-determination and personal autonomy. For instance, Vito, the protagonist of Dani Collins’ Bought by Her Italian Boss (2016), is hesitant to procreate because his father was a violent criminal; throughout this novel, mafia is portrayed as a genetic condition.

The Legacy of The Sheik

By featuring strong and contradicting patterns of attraction to and rejection of an orientalised male, E.M. Hull’s The Sheik (1919),[5] regarded as the archetype of the desert romance genre, establishes a useful point of departure for our discussion of Italian [End Page 9] romantic characters as closer to nature and more inclined to the expression of feelings and animalistic passions.

This dynamic lies at the heart of the great success of The Sheik, the popularity of its main character Ahmed Ben Hassan and its screen impersonator, Rodolfo Valentino, an Italian actor impersonating an Arab character. Analysing works from diverse literary genres, I have often come across an imagined overlapping of the Arab world with the Italian. In the novel An Italian Affair by Laura Fraser (2001), for instance, a version of the archetypal narrative of a young woman who leaves for Italy on an impulse after a painful divorce, the protagonist meets, on the island of Ischia, an older man, a professor. The professor’s peculiar charm comes from being half Arab and half Italian, and therefore, as the author puts it, from being ‘an Oriental.’ In this case, his ‘Italian half’ seems to add to his Oriental character. ‘Arab-ness’ and ‘Italian-ness’ are, in this text, associated on the basis not only of their perceived similarity as markers of a ‘Mediterranean nature,’ but, more importantly, on the basis of their perceived distance from the (post)modern world. All this is naturalized, that is to say described by the author as inborn:

He [the Professor] explains that it’s understood in his household that, once a year, he needs his solitude. He has to get away from Paris and just sit on an island and far niente, do nothing, so that he can be his Mediterranean self for a while. He needs to be able to relax completely, which is impossible to do in Paris. He is in part Italian and part Arab, and he has to spend some time being an Oriental man, living where the days are warmer and slower. It’s in his blood.” (Fraser 37)

The Sheik was extraordinarily successful upon publication, leaving a remarkably strong legacy on British popular literature.[6] Critical writings on the work have, so far, mainly focused on gender and sexual politics, neglecting perhaps to pay due attention to its racial and imperial discourses and their implications in and for popular British and Western literature, art and culture. There are, however, notable exceptions to this state of affairs, such as the studies by Hsu-Ming Teo and Elizabeth Gargano.

Gargano observes that “despite their provocative insights into the genre’s appeal to women, most critics […] downplay the novel’s construction of sex and gender relations within the context of race and class” (172). In response to this tendency, Gargano maintains that the main reason why Hull’s novels are still relevant to present-day cultural debates is not so much to be found in what they say about sexual politics and liberation, but because “they reveal the power that conventional stereotypes of gender and race could exert on the popular imagination during the early twentieth century and afterwards” (173).

The Sheik is described by the heroine of the novel, Diana Mayo, as a “splendid healthy animal” with “nothing effete or decadent” about him (Hull 277):

They were men, these desert dwellers, masters and servants alike; men who endured, men who did things, inured to hardships, imbued with magnificent courage, splendid healthy animals. There was nothing effete or decadent about the men with whom Ahmed Ben Hassan [the sheik] surrounded himself. (Hull 277) [End Page 10]

Descriptive expressions highlighting darkness and associating it with a primal masculinity, such as “dark piercing eyes,” “brown, clean-shaven face,” “fierce burning eyes,” “sleek black hair,” “dark restless eyes,” “lean brown fingers,” “dark, passionate eyes,” “brown, handsome face,” “dark, fierce eyes,” are recurrent throughout the novel (Hull, see for examples pages 56, 64, 78, 79, 80, 84), establishing the stylistic and discursive standard that has been discussed, in the first part of this essay, within the context of descriptions of the Mediterranean Man.

A Splendid, Healthy Animal

The notion of a dominant masculinity, primitive and aggressive (prompting comparisons between ‘oriental men’ and predatory animals), perceived in contrast to English cold-bloodedness and sexual restraint, has been commented upon by numerous scholars of The Sheik and the category the novel inaugurated:[7] “his feet made no sound on the thick rugs, and he moved with the long, graceful stride that always reminded her [Diana Mayo] of the walk of a wild animal” (Hull 139).

Harlequin short contemporaries feature numerous comparisons of Italian heroes with wild animals. Carried out in a mindless tone, they seem to be employed as simple markers of a taken for granted affinity between Mediterranean men and the natural world. Once again, Pérez-Gil notices the same thing occurring in relation to Spanish heroes, who, she observes, are often associated to wild animals (the bull, the cougar) in opposition to a less threatening masculinity incarnated by British men (10).

In Olivero’s Outrageous Proposal (2015) by Kate Walker, Dario, a winemaker, is “big and dark and disturbing” (loc 110), a “dangerous-looking pirate” (loc 259), and a “tall, dark, devastating stranger” (loc 367). His eyes are “bottomless dark pools threatening to drown [the heroine] in their depths” (loc 1449). Dario is associated, in the course of the novel, with a lion – “that leonine head swung around” (loc 88); a tiger – among other instances, “it seemed to her that [his] was the sort of smile that might appear on the face of a tiger when it realized that the deer it had its sights on was tremblingly aware of its presence” (loc 142); and a panther – “if she had opened the door to find a waiting panther, sleek, black, dangerous, standing before her, her nerves couldn’t have twisted any tighter into painful knots” (loc 744). Dario’s rival is Marcus, described as “a solid, stolid, Englishman with the pale colouring and eyes that marked him out as pure Anglo-Saxon. He had nothing of Dario’s stunning golden skin and sleek black hair” (loc 556).

This last description and comparison between a dull Englishman and an exotic Mediterranean Man also comes from a long tradition of literary antecedents. It reads as a much simplified version of the ones that, in The Sheik, put into comparison Ahmed with Diana’s suitors and her brother Aubrey. This latter character is depicted, Gargano observes, as “a cartoonish portrait of the played-out aristocrat, right down to the monocle he seems in danger of losing, Aubrey is implicitly feminized, since his qualities are the stereotypically ‘feminine’ ones of ‘pallor,’ ‘languor,’ and ‘courtesy’” (Hull 176).

The Sheik has effectively given voice to the dichotomy between the aggressive/primal masculinity associated with ‘oriental’ darkness and danger, and the pure/innocent femininity associated with British whiteness, as shown here: [End Page 11]

Diana’s eyes passed over him slowly till they rested on his brown, clean-shaven face, surmounted by crisp, close-cut brown hair. It was the handsomest and cruellest face that she had ever seen. Her gaze was drawn instinctively to his. He was looking at her with fierce burning eyes that swept her until she felt that the boyish clothes that covered her slender limbs were stripped from her, leaving the beautiful white body bare under his passionate stare. (Hull 56-57)

Similarly, mass-market romance novels, and the titles featuring Mediterranean men in particular, have solidified and re-shaped, in the course of the last century, this same notion, transforming it into a taken for granted and mindlessly reiterated dichotomy between ‘male dark danger’ and ‘female white purity.’ The heroine is, therefore, often stricken by the Mediterranean Man’s dark good looks but helpless to resist them. The following description, for instance, excerpted from Kate Hewitt’s short contemporary novel The Secret Kept from the Italian (2018), is strongly reminiscent of the description above: firstly, in its scopophiliac approach to the body of the Mediterranean Man; secondly in the juxtaposition of darkness with sexual appeal and danger (blade-like cheekbones); and thirdly, in the helplessness of the female character’s reaction when confronted with the overwhelming physical power of the hero:

Ink-dark hair flopped over his forehead, and strong, slanted brows were drawn over lowered eyes, so his spiky eyelashes fanned his high, blade-like cheekbones […] He’d taken off his tie and unbuttoned the top buttons of his shirt, so a sliver of bronzed, muscular chest was visible between the crisp folds of cotton. He fairly pulsated with charismatic, rakish power, so much so that Maisie [the heroine] had taken a step into the room before she even realised what she was doing. (loc 81)

Darkness/Eroticism/Danger

Patricia Raub confirms that the influence of The Sheik can still be observed in mass-market short contemporaries:

In the years immediately following publication of The Sheik, Hull’s characterization, plot, and setting were briefly but widely copied in the desert romances of the Twenties. Once the genre had died out in the Thirties, however, it was not until the advent of the Harlequin Romance in the 1960s that the literary elements of The Sheik reappeared in popular romantic fiction — and were finally detached from their original sandy setting. Like Diana Mayo, the Harlequin heroine is young, beautiful, and sexually inexperienced. Like Ahmed Ben Hassan, the Harlequin hero is tall, dark, and cruelly handsome. (124) [End Page 12]

If, as Gargano argues, during the first decades of the twentieth century, ‘desert novels’ “may have freed women readers from guilt by projecting sexual impulses onto a stereotypically sinister and ‘savage’ male” (171), I would like to add that this psychological, discursive and literary pattern, in specific contexts, endures, even if perhaps divested of most of its significance and urgency. Within this specific category, Italian heroes provide the possibility to re-introduce elements of racialized exoticism. Interestingly, these imagined conflations point, as it is often the case, at more than one origin. Teo, for instance, interprets the Sheik as a figure strongly reminiscent of the Gothic villain, a literary figure which has known several Italian instantiations. Teo emphasizes the peculiar blend of attractiveness and cruelty that characterizes the Sheik and that is found, in short contemporaries, in Italian men who need to be ‘tamed’ because they are fundamentally unreliable and prone to deceit.

For instance, in Bound by the Italian Contract (2014) by Janette Kenny, a novel set in an Alpine ski-station, hero and heroine are forced, by a series of circumstances, to work together for a period of time. Caprice will gladly accept to work for Luciano and sleep with him, but she will not compromise on emotional involvement: if Luciano is not ready to commit to her, she will leave him. Although Luciano’s Italian-ness is largely irrelevant, a convenient excuse for the use of some (pseudo)Italian during love-making scenes, his ‘foreignness’ is stressed as an element of otherness, one which sets him apart from the normative American heroine.[8] Luciano is handsome, commanding and self-confident, but also a man potentially capable of transforming himself into a ‘human animal’ prone to anger, violence and deceit: “and the designers quickly left, leaving her alone with a very irate, very intense Italian” (loc 924). “Dear God, what a monumental mistake she’d made aligning herself with an Italian, even if he was a man she’d started to trust again” (loc 1682).

Renzo, the protagonist of The Italian’s Pregnant Virgin (2016) by Maisey Yates, a cynical businessman who will learn to love again after a grave disappointment, poses as a gothic villain in the novel: “Esther’s voice cut through the darkness. He knew he must look like quite the looming villain, standing in the doorway dimly backlit by the hall” (loc 2009). His skin is described as “burnished” (loc 954, 1124) and he has “the intensity of a predator gleaming in those dark eyes” (loc 1714). Moreover, the dichotomy dark sensuality/danger is, once again, invoked in the description below, in which obsidian replaces chocolate as a dark, appealing, but potentially dangerous material:

Beautiful was the wrong word for Renzo, she decided. He was too hard cut. His cheekbones sharp, his jaw like a blade. His dark eyes weren’t any softer. Like broken edges of obsidian. So tempting to run your fingers over the seemingly smooth surface, until you caught an edge and sliced into your own flesh. (loc 535)[9]

Perhaps one of the most significant and enduring aspects of the legacy of The Sheik for the genre is the canonization of the threefold construct of darkness/eroticism/danger, which finds in short contemporary romance novels featuring Mediterranean Men a convenient (because politically uncontroversial) outlet. [End Page 13]

A Warm Language and a Passionless One

Lastly, the depiction and use of the English language as a marker of dullness and lifelessness, as Gargano argues in her study, is another important trope of the foreign and the exotic still detectable in numerous short contemporary romance novels. Ahmed loses exotic and erotic appeal when he, at the end of the story, ‘becomes English,’ dismissing his disguise as an Arab sheik and returning to speaking English, one of his native languages. Diana observes that: “his voice sounded dull and curiously unlike, and with a little start […] realized that he was speaking English” (Hull 286). English is perceived as the quintessentially modern and unemotional language, thoroughly inappropriate for the expression of intimate feelings.

There are countless references, in contemporary Harlequin novels, to the perceived exotic and erotic quality of the Italian language, and numerous comparisons of it to the English language perceived as unemotional and inexpressive. For instance, in the already mentioned Dante’s Unexpected Legacy, Dante’s exotic character is conveyed through his accent and use of language. Cesare’s accent “underl[ies] every syllable with a honeyed mellifluence that spiralled sinuously round her to create the strongest sense of dislocation” (Graham, The Billionaire’s Bridal Bargain, loc 256); whereas when Max from Taming her Italian Boss speaks English instead of Italian, Ruby, the heroine, observes that it is:

A pity, because when he spoke Italian he sounded like a different man. Oh, the depth and tone of the voice were the same, but it had sounded richer, warmer. As if it belonged to a man capable of the same passion and drama as the woman he was chasing upstairs. (Harper, loc 633)

The language, the capacity for passions and warm feelings are here all conflated into one notion of ‘Italian-ness’ that, in this category of novels, is at once conventionally multi-layered and easily recognizable.[10]

Dante is supposed not to possess a perfect command of the English language, but, at times, he expresses himself in an oddly contrived style: “let us enjoy this unexpected gift of time together” (George, loc 364). Amusing contradictions aside, all Italian heroes in this literary category speak appallingly bad Italian. Whether they are American of distant Italian origin, or Italians on a short holiday to the United States, England, or Australia (where most short contemporaries are set), they all encounter serious problems with the Italian grammar.[11] This feature of the genre contributes to the impression of an imagined split between English as a modern language and Italian as a folkloristic one, one that does not need to be properly researched but can be evoked with approximation and carelessness.

Concluding Remarks

In this essay, I looked at ‘Italian themed’ short contemporaries as texts that capitalize on familiar tropes and images. Although these have ceased to be directly connected to the larger imperial episteme, they still carry literary, cultural, and discursive [End Page 14] suggestions historically and culturally informed, demonstrating the powerful and durable nature of discursive connections between literature and colonial values.

Regis explains that, in The Sheik, when Ahmed Ben Hassan is revealed to be half English and half Spanish, he does not completely cease to be exotic. He is, in Regis’ words, “exotic in his origins but still European” (115). My discussion aimed precisely at exploring the notion of a ‘milder brand’ of exoticism, situated somewhere between sameness/normalcy/familiarity and downright otherness.

Discussing Harlequin novels, Regis furthermore argues that “when a novel is that brief, the author must pare the story down to its essentials […] what is left is a distillation of the romance novel, contained primarily in scenes between the heroine and the hero” (160, italics mine). In this essay, I have shown how, along with the distillation of the essential narrative elements of the romance novel, another kind of ‘distillation’ takes place: the discursive patterns that have, historically and culturally, been employed in the description and characterization of Italy and Italians get ‘extracted’ from larger forms of literary and discursive patterns and are expressed within the strict narrative parameters of this literary genre.

The result is a discourse of the exotic and on the exotic nature of Southern Europeans, and Italians in particular, that needs very few ciphers and code-words (“olive skin,” “chocolate eyes,” “dark gaze,” “mysterious dark eyes”) to be evoked in its larger significance. Certain terms, expressions and images are employed to summon a much wider tradition, literary and discursive at large, that relies on a dichotomy between the normative and the exotic.[12]

Gargano argues that the figure of the sheik “exemplifies one incarnation of an enduring division that modern Western consciousness has achingly perceived in itself: lost possibilities of passions and ‘primitive’ authenticity juxtaposed against the restrictive responsibilities of ‘civilization’” (184). In the course of this essay, I have indicated ‘Italian’ short contemporaries as a venue in which this kind of split is continuously re-enacted. Italian men, placed in a limbo between civilization and the primitive, act as contemporary catalysts of such long-lost primal instincts and passions.

Hence, in spite of the narrow tracks along which short contemporaries travel, they manage to convey the multiple layers of a long tradition of representing Italian otherness: from the menacing character of the Gothic (Italian) villain, to the notion that sees Italians in partial discontinuity with a (British, Anglo-American) ideal of civilization, closer to nature and the unmediated expression of feelings. All these tropes are accommodated within the creative parameters of the category, making of it a worthy venue of inquiry into processes of identity formation and cultural representation.

[1] The origin of the category is conventionally placed at the beginning of the last century with books such as The Garden of Allah (1904), The Spell of Egypt (1910) and The Call of the Blood (1906), all three novels written by English author and satirist Robert S. Hichens. E.M. Hull’s The Sheik and its filmic adaptation, however, are widely regarded as having established the main creative coordinates for the ‘desert’ (or ‘sheik’) romance category.

[2] Jarmakani argues that sheiks “operate as key ghostly presences in a wider romance genre primarily focused on white characters coded as representing universal experience” (912). The same, I argue, holds true for Mediterranean Men and Italian men in [End Page 15] particular, a category this particular subgenre racializes through descriptive repetition and compulsive reiteration of markers connected with ‘darkness.’

[3] On the topic of the association of Italian romantic heroes with works of art, see Pierini, “He Looks like He’s Stepped Out of a Painting”.

[4] Renzo, the Italian protagonist of The Italian’s Pregnant Virgin, looks like “a statue straight from a Roman temple” (Yates, loc 1117).

[5] Hsu-Ming Teo summarizes the plot of the novel as “the story of an aristocratic but tomboyish English virgin who, in her travels to French colonial Algeria, is kidnapped by an Arab sheik and raped many times. She eventually falls in love with this ‘brute’ of an Oriental ‘native.’ […] As for the sheik himself, the violent and priapic Ahmed Ben Hassan is reduced to repentance and redeemed by his love for Lady Diana Mayo. He reverts to ‘civilized’ standards of patriarchal European gender norms, presumably forsaking rape and promiscuity […] The two live happily ever after in the desert, leaving the reader with the final spectre of an aristocratic English couple ‘gone native,’ it is true, but reigning imperialistically over the unruly Bedouin tribes of the Sahara in an area which is nominally under French colonial control” (2-3).

[6] The film version of the novel was an extraordinary success that ignited ‘sheik fever’ throughout the Western world. The film featured Rodolfo Valentino, a Southern Italian, in the role of the Sheik. On the filmic transposition of Hull’s novel, see Teo. For a critical reading of Hull’s subsequent literary production, see Turner. In this study, Turner discusses, in particular, The Sons of the Sheik (1925), The Shadow of the East (1921), The Desert Healer (1923), The Lion Tamer (1928), The Captive of the Sahara (1945) and The Forest of Terrible Things (1939). Lastly, for a discussion of the ‘female gaze’ and Rodolfo Valentino, see Nava.

[7] See Ardis, and also Raub. Gargano also observes that the Sheik is compared by Diana to a tiger: “a graceful, cruel, merciless beast” (179).

[8] Luciano’s physical attractiveness, at times of a menacing quality, is described, once again, through frequent references to his olive skin and classic works of art: “to her surprise, a ruddy flush streaked across his olive-hued cheekbones” (Kenny, loc 284); “She peered at his resolute features and thought marble statues didn’t look as hard or inflexible” (Kenny, loc 1732). Some of the recurring qualifications used by the author in conjunction with the adjective “Italian” are: “handsome Italian,” (“boisterous Italian,” “imposing Italian” (Kenny, loc 61, 54, 165, 166).

[9] In The Italian’s Ruthless Seduction by Miranda Lee (2016), Sergio “had never believed himself a ruthless man – or a vengeful one – it seemed he was even more Italian than he’d thought” (loc 366).

[10] Furthermore, the quality of darkness that belongs to the physical appearance of Italian heroes is sometimes transposed onto the language: “the dark, deep accent tautening every muscle in her already tense body” (Graham, The Italian’s Christmas Child, loc 1015).

[11] In Dante’s Unexpected Legacy, for instance, the use of Italian is consistently incorrect throughout the text, regardless of whether it is spoken by the Italian characters, the British, or the narrating voice. In Between the Italian’s Sheets there are frequent mistakes. Particularly amusing is the use of the sentence “siete il fuoco della mia anima,” pronounced by the hero in the heat of passionate sex. Although grammatically correct, it is ludicrous for its featuring of the extremely formal and out-dated way of addressing an interlocutor in Italian. [End Page 16]

[12] Throughout the modern centuries, a dominant descriptive pattern of the Anglo-Italian encounter in modern and contemporary Anglophone fiction has been focusing on representing Italy as a unique constellation of counter-values to Anglo-American culture and its ethos. This tradition can be characterized as a discursive formation reiterating the construct of Italy’s exoticism and a particularly complex and multi-layered notion of ‘primitivism’ (McAllister; Pierini, 2016). In contrast to puritanism, in particular, Italy has been construed and represented as one of the model spaces for sexual freedom and indulgence (Girelli). The modern trope of sensual and sexual Italy can be traced back to the cultural and social practice of the Grand Tour (eighteenth century) which consecrated Italy as a land of aesthetic beauty and sensual pleasures (Hom). [End Page 17]

Works Cited

Primary sources

Anderson. Natalie. Between the Italian’s Sheets. Mills & Boon, 2009. E-book.

Collins, Dani. Bought by Her Italian Boss. Harlequin, 2016. E-book.

Conder, Michelle. The Italian’s Virgin Acquisition. Harlequin, 2017. E-book.

Faye, Jennifer. The Playboy of Rome. Mills & Boon, 2015. E-book.

Frances, Bella. The Italian’s Vengeful Seduction. Harlequin, 2017. E-book.

Fraser, Laura. An Italian Affair. Pantheon Books, 2001.

George, Catherine. Dante’s Unexpected Legacy. Harlequin, 2014. E-book.

Graham, Lynne. The Billionaire’s Bridal Bargain. Harlequin, 2015. E-book.

Graham, Lynne. The Italian’s Christmas Child. Harlequin, 2016. E-book.

Graham, Lynne. The Italian’s Inherited Mistress. Harlequin, 2018. E-book.

Graham, Lynne. The Italian’s One-Night Baby. Harlequin, 2017. E-book.

Harper, Fiona. Taming her Italian Boss. Harlequin, 2014. E-book.

Hewitt, Kate. The Secret Kept from the Italian. Harlequin, 2018. E-book.

Hull, E.M. The Sheik. Small, Maynard & Company, 1921.

Jackson, Brenda. Delaney’s Desert Sheikh. Harlequin, 2002. E-book.

Kenny, Janette. Bound by the Italian Contract. Harlequin, 2014. E-book.

Lee, Miranda. The Italian’s Ruthless Seduction. Harlequin, 2016. E-book.

Marinelli, Carol. The Italian’s Touch. Harlequin, 2015. E-book.

Metcalfe, Josie. The Italian Effect. Harlequin, 2001. E-book.

McDonagh, Margaret. The Italian Doctor’s Bride. Harlequin, 2006. E-book.

Reid, Michelle. The Italian’s Revenge. Harlequin, 2000. E-book.

Walker, Kate. Olivero’s Outrageous Proposal. Harlequin, 2015. E-book.

Yates, Maisey. The Italian’s Pregnant Virgin. Harlequin, 2016. E-book.

Secondary Sources

Ardis, Ann. “E. M. Hull, Mass Market Romance and the New Woman Novel in the Early Twentieth Century.” Women’s Writing, vol. 3, no 3, 1996, pp. 287-296.

Gargano, Elizabeth. “English Sheiks and Arab Stereotypes: E.M. Hull, T.E. Lawrence, and the Imperial Masquerade.” Texas Studies in Literature and Language, vol. 48, no. 2, Summer 2006, pp. 171-186.

Girelli, Elizabetta. Beauty and the Beast: Italianness in British Cinema. Intellect, 2009.

Hom, Stephanie Malia. The Beautiful Country: Tourism and the Impossible State of Destination Italy. University of Toronto Press, 2015.

Jarmakani, Amira. “Desiring the Big Back Blade: Racing the Sheikh in Desert Romances.” American Quarterly, vol. 63, no. 4, December 2011, pp. 895-928.

McAllister, Annemarie. John Bull’s Italian Snakes and Ladders: English Attitudes to Italy in the Mid-nineteenth Century. Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2007.

Mulvey, Laura. “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” Film Theory and Criticism: Introductory Readings, edited by Leo Braudy and Marshall Cohen, Oxford University Press, 1999, pp. 833-44.

[End Page 18]

Nava, Mica. Visceral Cosmopolitanism: Gender, Culture and the Normalisation of Difference. Berg, 2007.

Pérez-Gil, María del Mar. “Representations of Nation and Spanish Masculinity in Popular Romance Novels: The Alpha Male as ‘Other’.” Journal of Men’s Studies, vol. 27, no. 2, 2019, pp. 1-14.

Pierini, Francesca. “‘He Looks like He’s Stepped Out of a Painting’: The Idealization and Appropriation of Italian Timelessness through the Experience of Romantic Love.” Journal of Popular Romance Studies, Volume 9 (2020).

Pierini, Francesca. “Trading Rationality for Tomatoes: The Consolidation of Anglo-American National Identities in Popular Literary Representations of Italian Culture.” Anglica: A Journal of English Studies, vol. 25, no. 1, 2016, pp. 181-197.

Raub, Patricia. “Issues of Passion and Power in E.M. Hull’s The Sheik.” Women’s Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal, vol. 21, no. 1, 1992, pp. 119-128.

Regis, Pamela. A Natural History of the Romance Novel. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2003.

Teo, Hsu-Ming. “Historicizing The Sheik: Comparisons of the British Novel and the American Film.” Journal of Popular Romance Studies, vol. 1, no. 1, 2010, http://jprstudies.org/ 2010/08/historicizing-the-sheik-comparisons-of-the-british-novel-and-the-american-film-by-hsu-ming-teo/. Accessed 5 September 2019.

Turner, Ellen. “E.M. Hull and the Valentino Cult: Gender Reversal after The Sheik.” Journal of Gender Studies, vol. 20, no. 2, 2011, pp. 171-182.

[End Page 19]