Imagine a pregnant woman. Is she overweight? Does she look like she was too tired to care about the clothes she put on? Is she waddling around on swollen feet? The answer to [End Page 1] all of these questions is most likely “no.” Representations of pregnancy in Western cultures currently revolve around pregnancy as a form of success: pregnant celebrities wear the latest trends and look fabulous, active mothers choose their preferred model of jogging strollers, and a whole array of films feature pregnant career women. In fact, the genre of “romcoms” now includes “momcoms,” stories “that promise women romance, love, and sex, all through the transformative power of pregnancy” (Oliver 3). However, while the display of the pregnant body suggests a form of female empowerment, it simultaneously creates new expectations of women.

Pregnancy has become an index for women with which to measure their success, even in genres that are mostly produced by and for women. Writing about chick lit, for example, Cecily Devereux states that “[t]he conclusion, . . . with or without the wedding, is ideologically driven, reaffirming a conviction in the propriety and perhaps necessity of heteronormative union and babies as the conclusion to a woman’s young life” (222). Category romance titles that focus on pregnancy similarly employ pregnancy to reinforce patriarchal ideologies by participating in a particular representation of pregnancy which reinforces traditional family values and demonstrates that “a childless life is worthless, and anyone who doesn’t want kids must be bitter and selfish and morally deficient” (Kushner). In these pregnancy novels, the heroine’s fulfillment —the happy ending that is made possible by having a baby—is dependent on the choices she makes, such as marrying the father or changing her style of dress. This dependency perpetuates stereotypes for distinguishing “good” from “bad” mothers. Robyn Longhurst comes to the conclusion “that bad mothers tend to be (re)presented as lacking in a number of ways,” such as financial means or a husband (118).

That is not to say that category romance as a whole portrays pregnancy as woman’s destiny, as numerous authors envision a happy end without a baby, and some, such as Penny Jordan’s The Reluctant Surrender (2010), even feature a couple actively deciding against having a baby without being any less fulfilled for it.[1] Likewise, depictions of single motherhood exist that do not represent the heroine as a “bad” mother. Again, Jordan would be another good example with The Sicilian’s Baby Bargain (2009).[2] Yet, there is no shortage of novels that do end with a baby, many of which focus on the actual time or discovery of the pregnancy, rather than those set after the birth. This subset of category romance novels is the subject of my analysis, and I will refer to these texts as “pregnancy narratives” from here on.

I focus on category romance because the women in this genre are not desperate for a baby;[3] in fact, most pregnancies are unplanned. Category romance does not presuppose that women want or need babies; yet, it focuses on the heroine’s fulfillment, and in the narratives that revolve around pregnancy—rather than the raising of children or the time after the birth—this fulfillment is only made possible through the heroine’s pregnancy. This type of narrative thereby creates career women who unfailingly learn that only becoming pregnant can lead to true happiness, which is different from chick-lit where most of the protagonists, such as Bridget Jones, actively yearn to leave singlehood behind in favor of domesticity.

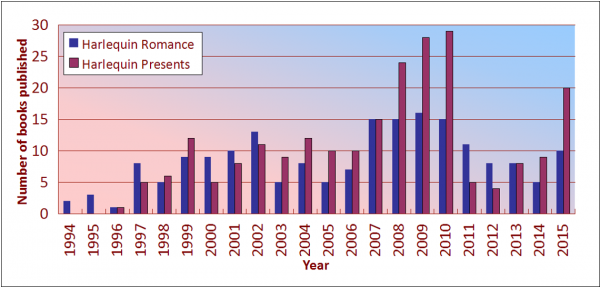

My sample of category romance novels is based on publications by Harlequin, due to the publishing company’s long history and its dominating place in the romance market. They have furthermore all been selected at random on various trips to secondhand bookstores. I chose titles that clearly indicate a pregnancy narrative, but the individual texts depended on what was available at the stores at the time of my visit. Within my sample, pregnancy as the [End Page 2] vehicle for the plot—and something clearly identified by the novel’s title as an important part of the narrative—first appeared in 1994, when Emma Goldrick’s Baby Makes Three was published in the “Harlequin Romance” series. The “Presents” series, which Harlequin’s website describes as “the home of the alpha male” with a focus on “sky-rocketing sexual tension” and thus making the sexual affair the center of the story (“Harlequin”), followed in 1997 Emma Darcy’s Jack’s Baby, whose title clearly identified it as a pregnancy story. From then on, pregnancy was a recurring theme among the publications (Figure 1).[4]

The theme even sparked several mini-series in the new millennium, such as “Bought for Her Baby” (2008) or “Expecting!” (2006-present).

As Figure 1 shows, pregnancy titles in the “Romance” line increased from an average of seven titles per year at the end of the 1990s to about fifteen per year after 2007. The “Presents” imprint took even more enthusiastically to the theme and published more than twenty-five titles in 2009 and 2010. The decrease in titles for the following years, until the number picked up again in 2015, could be related to the “crescendo [of criticism] in 2009” aimed at “Nadya Suleman, the so-called Octo-Mom and her decision . . . to use reproductive technology to give birth to multiples when she was already the mother of six and dependent on welfare” (Rogers 121). Suleman had several media appearances in 2010, and her dependency on welfare, use of rehabilitation facilities, sentence to community service for welfare fraud, and alleged statements about regretting the decision to have children continued to be chronicled for several years afterward (“Natalie”). The negative public opinion formed through this media coverage—while based on Suleman’s use of reproductive technologies and reliance on welfare—might perhaps have resulted in less Harlequin pregnancy narratives, if either the publisher itself or the writers became more hesitant about the reception these texts would receive on the market.

The interest in the pregnancy theme, despite the temporary decrease in titles, is ongoing. It emerged as a trend in the mid-1990s, mirroring a development in Hollywood films as well as in women’s magazines (Boswell; Hine; Sha and Kirkman), and is related to [End Page 3] the achievements of Second Wave feminism. The women’s movement in the 1970s and 1980s advocated a re-evaluation of pregnancy, as writers like Luce Irigaray and Julia Kristeva “attempted to articulate a positive account of pregnancy and of the maternal body” (Oliver 21). Popular culture joined this debate in 1991 when Vanity Fair’s cover featured a naked and very pregnant Demi Moore. Just how problematic the publicly displayed, uncovered pregnant body was at that time can be inferred from the shocked reaction that the image caused. Gabrielle Hine states that “the issue was widely criticized as offensive and numerous stores refused to sell it,” whereas Moore’s post-partum body on the cover in 1992—equally naked despite the body paint used to give the impression that she is wearing a male suit—“provoked less debate” (581). Moore’s picture broke a taboo, and others—most notably Beyoncé’s recent photoshoot, in which she presented her heavily pregnant belly in underwear—followed. By now, entire blogs are dedicated to images of pregnant celebrities in various states of dress or undress, a phenomenon to which I will return in my discussion of the novels’ covers.

Category romance likewise reacted to social changes in the course of its publication history. In 1980, Tania Modleski argued that Harlequin novels “are always about a poor girl marrying a wealthy man” (443) and that the “genuine heroine must not even understand sexual desire” (444), but as jay Dixon shows in her work on Mills and Boon fiction between 1909-1995, these claims are not accurate when it comes to category romances from the early twentieth century, and the books “have changed over the past decades” even more dramatically (5). Nowadays, the heroine can be a CEO (Jessica Gilmore’s The Heiress’s Secret Baby, 2015), or own a company (Kandy Shepherd’s From Paradise…to Pregnant, 2015), and a sexually assertive heroine can be found across several imprints, some of which even feature sex as a fundamental part of their storyline, such as “Dare” (2018-present), “Desire” (2011-present), “Blaze” (2001-2017) or “Presents” (1973-present). The incorporation of “some aspects of feminist values—much greater emphasis on women’s sexual desire and much less on the requirement to be a virgin bride, more career women and greater independence for the romantic heroine, for example” even led to a pushback from feminist critics against the initial negative evaluation of the genre (Weisser 132-33). The feminist movement affected popular culture, and pregnancy was taken up as a theme in category romance with the same enthusiasm as it was in Hollywood or in women’s magazines.

Before I address the representation and function of pregnancy at the level of the narrative to show that the heroine’s fulfillment in pregnancy narratives is always dependent on having a baby, let me offer a short analysis of the covers, which also participate in shaping the image of the “good” mother by attaching this value to certain dress and lifestyle choices. In their studies on the representation of pregnancy in Australian and New Zealand women’s magazines respectively, Hine and Sha and Kirkman observe that the monitoring of pregnant celebrities is used to create stereotypes of “good” and “bad” mothers. With regard to Australia’s magazine culture, Sha and Kirkman state that the “magazines tended to feature ‘good’ women (who dressed with restraint) and ‘bad’ women (who did not)” (363). Hine comes to a similar conclusion for her New Zealand selection with regard to discipline, arguing that “[m]agazines . . . associated the ‘success’ of a pregnancy with the size and appearance of the pregnant and post-partum body. Across the sample, pregnant celebrities were represented as graced with willpower, luck, and a fast metabolism” (585). Both magazine samples featured largely U.S. celebrities, which makes their findings relevant for [End Page 4] the North American Harlequin covers. About half of the covers for both imprints feature visibly pregnant bodies.[5]

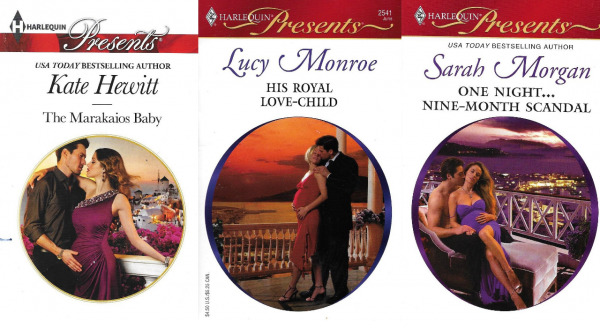

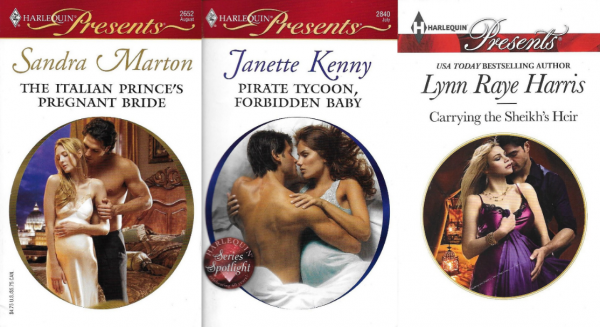

The covers in my sample from “Harlequin Presents” bear the most resemblance to pictures taken of pregnant celebrities, with the women on the covers in Figure 2 all wearing fancy dresses, jewelry (in some), and high heels, when their feet are shown. None of them has put on any weight during their pregnancies, and they all look styled for a night out. This presents women as able to maintain a slim body throughout their pregnancies, while still dressing with style. Hines’s conclusion that current “images of pregnancy encourage the display of the pregnant body, but also endorse the discipline of the pregnant form through an investment in feminine consumer culture” (587) is supported by these covers.

If we compare these covers to pictures taken of pregnant actresses at the Oscars, as seen in Figure 3, we notice striking similarities both in dress and in the angle at which the photo was taken, which often highlights the pregnant belly. [End Page 5]

Figure 3: Jenna Dewan Tatum (2013), Natalie Portman (2011), and Jessica Alba (2008). Images InStyle: http://www.instyle.com/awards-events/red-carpet/oscars/pregnant-celebs-oscars-gallery

Further pictures can also be found on US Weekly’s blog “Bump Watch,” which is dedicated to the collection of pictures of pregnant celebrities. Aligning the cover models with the media’s representations of famous pregnant women might also suggest that the heroines of the novels will experience a life of glamor, riches, and success despite—or because of—their pregnancy.

Other Harlequin covers focus on the more private setting of the bedroom, with the heroine dressed in modest—but still sensuous—nightgowns that heighten her femininity and vulnerability, as can be seen in Figure 4:

[End Page 6] The pregnant bodies on “Harlequin Romance” covers are not clad in evening dresses or decked out in jewelry, favoring instead modestly dressed mothers-to-be, but the slimness and femininity of the expectant mothers is highlighted by their attire (Figure 5). These covers contribute to an ideal—slim, stylish, well-groomed—that is unattainable for most pregnant women who, in contrast to famous celebrities, cannot rely on nannies, personal assistants, or expensive grooming treatments. This representation of the successful mother puts additional pressure on women to conform to certain expectations, in addition to negotiating (single) motherhood and their jobs.

The scope of this article cannot include a more in-depth examination of the covers, even though further exploration of the history of the relationship between modeling Harlequin covers on celebrities would certainly prove insightful; however, I find this short introduction useful in that the covers already indicate certain patterns when it comes to the representation of pregnancy in category romance. On the level of the narrative, these patterns emerge through choices that the heroine makes, be it by contacting the father or by giving up her job. By the end of the novel, the reader is implicitly aware that the female protagonist’s fulfillment and her choices are mutually constitutive.

I will first focus on pregnancy narratives in Harlequin’s “Presents” line. My sample consists of fifteen texts that range from 2002-2015 that are clearly identified by their title as a pregnancy narrative. The selection here, too, is based merely on the availability of these [End Page 7] texts at the secondhand bookstores that I visited. The imprint, as the following analysis will show, portrays traditional gender roles. This portrayal stems from the imprint’s requirement to have an alpha male hero who is so influential and wealthy that “there’s nothing in the world his powerful authority and money can’t buy” (“Harlequin”); his exaggerated status causes a socioeconomic divide between him and the heroine that makes her powerless against him in the public sphere and “explains” his dominant behavior in the domestic sphere. True to the imprint’s specifications, the men in these stories are usually billionaires or royals and often presidents or CEOs of international companies, something that is almost always reflected by the title. In that category we have Emma Darcy’s Ruthless Billionaire (2009) or Lynn Raye Harris’s Carrying the Sheikh’s Heir (2014), to name just a few: both titles clearly indicate how powerful the male protagonist is. There are others in which the focus is on conception out of wedlock, such as Lucy Monroe’s One Night Heir (2013) and Pregnancy of Passion (2006) or Miranda Lee’s The Secret Love-Child (2002). “Harlequin Presents” also favors exotic locations and it is therefore not surprising that several titles highlight the European origins of the male protagonist, such as, for example, Maggie Cox’s The Italian’s Pregnancy Proposal (2008) or Sandra Marton’s The Italian Prince’s Pregnant Bride (2007).

In my sample, in “Harlequin Presents” narratives that are clearly identified as a pregnancy narrative and whose focus is on the time of the pregnancy, the pregnancy is never planned. It is often even devastating for the heroine because the pregnancy is frequently discovered just after the heroine and the hero break up. Characteristic of Harlequin romances, the separation is often caused by a misunderstanding or personal fears, as in Lucy Monroe’s His Royal Love-Child (2006), in which Danette agrees to have a secret affair with the prince of an Italian island. Six months later, however, Danette does not want the affair to be secret anymore, which is more than what her lover wants to offer, so she ends the relationship. In another scenario, the characters meet for the first time and end up having a one-night stand, often leading to a longer affair before the pregnancy is discovered. Both the Princess of Surhaadi in Carol Marinelli’s Princess’s Secret Baby (2015) and perfume-maker Leila in Abby Green’s An Heir Fit for a King (2015) end up in bed with a man they only met hours or at most a day earlier.

A small portion of pregnancy novels—three out of fifteen in the sample—evolve from a desire for revenge. In those cases, the hero has a dark secret which drives him to pursue the heroine and tie her to him through marriage and pregnancy, with the plan to destroy her. However, while carrying out his plan, he realizes that she is a different person than he had previously thought and he falls in love with her. Conflicts then arise because the heroine discovers his secret plan, and he has to convince her that his love is now real.

In all cases, the narrative jumps from the conflict to the discovery of the pregnancy, which can be as early as the first month post-conception or as late as the third month. In ten out of fifteen novels, the couple then agrees to enter a marriage of convenience for the sake of the baby. The remaining five novels include two in which the couple are already married because it was part of his plot, and three which conclude with marriage at the end. Marriage, so it is explained, is necessary to provide the child with a stable home. Pregnancy narratives in “Harlequin Presents” are filled with protagonists who grew up as illegitimate and unacknowledged children, or unloved and from a dysfunctional family. In Janette Kenny’s Pirate Tycoon, Forbidden Baby (2009), Keira has suffered her whole life from being kept a secret by her father and abandoned by her mother, and Margo, Kate Hewitt’s protagonist in [End Page 8] The Marakaios Baby (2015), grew up with a mother addicted to crystal meth and no father; both vow to provide their baby with a full set of parents.

At the point that the heroine proposes or agrees to a marriage of convenience, she is convinced that it will be a business-like arrangement without love. The heroes have similar family backstories: Talos in Lucas’s novel Bought: The Greek’s Baby (2010) grew up fatherless and then had to find out that the man he looked up to as a substitute father was corrupt; Monroe’s hero in His Royal Love-Child, Marcello, could never compete with his brother for his father’s affection and was kept out of the family business for years after the father died; and Alex in Tina Duncan’s Her Secret, His Love-Child (2010) was the victim of an abusive father. This observation supports Laura Vivanco’s assessment in her article “Feminism and Early Twenty-First Century Harlequin Mills & Boon Romances” that category romance depicts patriarchy not as detrimental exclusively for women, but as damaging for men as well (1077).

The decision to marry the father—even without love—always proves to have been the “right” one by the end of the novel, as it leads to the heroine’s fulfillment. By retrospectively affirming the heroine’s decision, the pregnancy narratives in both imprints that I examine here contribute to notions of what constitutes a “good” or a “bad” mother. The ideal of the “good” mother includes socioeconomic factors, as Dorothy Rogers, chair of the department of Philosophy and Religion at Montclair State University, pointed out in 2013:

Even in our relatively enlightened age, just about the worst thing a woman can do . . . is bring a child into this world when she [the mother] is unattached, uneducated/undereducated, unemployed/underemployed, without the social sanction of marriage, and with no economic backing—in short, to become the much-maligned welfare mother who is assumed unable to be a ‘good mother.’ (121)

“The perception was,” as Rogers states, that if the birthmother’s pregnancy was unplanned, her “main task was to ‘make things right’” (122). In the pregnancy narratives of the “Presents” imprint, all heroines do indeed inform the father of his new status and agree to a marriage of convenience for the sake of the child.

In order to be a good mother, the heroines have to do everything within their power to provide their child with two parents—married, preferably—financial security, and a home. It might mean giving up career opportunities, moving closer to social support networks, and/or marrying the father. In the course of these narratives, the heroine proves that her child will always come first, that she will protect it, and raise it with love. This need for proof appears as part of the plot as well, because the “Presents” heroes consider themselves the owner of the child, while the mother—if not a “good” one—can be removed from the picture. The heroine therefore needs to demonstrate her worth if she wants to keep her child.

The feelings of the father toward the baby are almost never questioned, despite the unintentional pregnancy. Only one out of fifteen heroines, Morgan’s heroine in One Night…Nine Month Scandal (2010), worries that the hero does not want the child. While some fathers question their paternity in the beginning, it is never in doubt that they want the child as long as it is theirs. The heroes, however, are not emotional about the prospect of fatherhood. Rather, it is about the fact that it is “his” child and ensuring that “his” child will [End Page 9] receive “his” name, as well as everything he himself had lacked growing up. In one of the revenge narratives, Bought: The Greek’s Baby (2010), in which the father is convinced that the heroine is a shallow, cold, and selfish person, he threatens her with taking full custody of the child when he learns of the pregnancy. This is a common scenario across the texts, and several fathers use the same threat to ensure that the heroine agrees to their conditions.

The battle for custody as the right of ownership suggests that the family model in category romance is based on “the property model of parenthood” (Rogers 128). This model, as Janet Farrell Smith argues, has its origin in the patriarchal household of Roman times, when “parental rights and responsibility have explicitly overlapped with property rights” (113), giving the male head of the household the right to treat his child as he would anything else he owns, meaning he could destroy it, let it live, or sell it to someone else.

The modern “Harlequin Presents” pregnancy narrative reflects the idea that patriarchal control is also connected to economic power: the threat of being able to buy the child with the means of a lawyer and the resulting fear in the female protagonist stresses the economic divide between the hero and the heroine. The hero not only wields significant power in the business world, but his financial means far exceed those of the heroine. While the difference in wealth between men and women is realistic—since women in most nations earn less than men[6]—these texts fictionally perpetuate this divide and present marriage as a form of prostitution to which the woman has to agree if she wants access to her child. Several heroes, such as Duncan’s Alex Webber or Hewitt’s Leo Marakaios, even explicitly state that they expect their sexual relationship to resume within their marriage agreement.

The representation of the pregnancy itself is limited to a few stereotypes, while the fetus itself is almost completely absent from the texts;[7] this is also true of medical technology with the exception of ultrasound. All women in these fifteen novels suffer from morning sickness which alerts them to their condition—the heroine’s weakness due to her nausea, as well as back pain or swollen feet, excuse her vulnerability, to which the hero responds by taking care of her. She is carried over hot sand, put into cars, put to rest, or escorted away from crowded gatherings. Her mobility, so the novels suggest, is limited and dependent on masculine strength and chivalry. She is not necessarily confined to a bed, but several heroes ensure that the heroine is kept in one location, usually without access to modern technology, and not one of the heroines keeps working once the hero discovers the pregnancy.[8] For that reason, the treatment of the heroine with its focus on rest rather than on exercise or mental stimulation is reminiscent of the rest cure, a nineteenth-century practice that was believed to alleviate depression, particularly that of women after giving birth.[9]

While the rest cure was criticized in popular fiction as early as 1892 in Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s The Yellow Wallpaper, and even though it is medically recognized as ineffective or even counterproductive, it is revived in the “Harlequin Presents” pregnancy novel as an act of care. It is used to present the men as attentive to the heroine’s emotional and physical needs and enables her to be taken care of instead of fulfilling the role of nurturer herself. Only a small number of novels cover the entirety of the pregnancy from discovery to birth. The majority confines itself to a timeframe of a few months, often ending before the event of the birth. It is therefore not possible to draw any conclusions from my samples about the hero’s role as care-giver with regard to the baby, a question that presents a trajectory for further research. [End Page 10]

The pregnant body is almost never described explicitly. The size of the stomach is never mentioned once it outgrows a small bump, despite the fact that couples in the novels still have sex in the sixth month of pregnancy or later. The narration instead focuses on the transformation of the heroine’s body into a more feminine one; pregnancy softens her and makes her more attractive. Her withdrawal from the public sphere can then be read as being rewarded with beauty, constituted by traditional models of femininity. Attention is, however, paid to her breasts and how pregnancy has enlarged them, which again makes her more desirable, and perpetuates stereotypical views on what makes women attractive. While chick-lit protagonists are explicit about their desire to conform to the norms of the fashion and beauty industries—which can be considered replacements of patriarchal discourse (Jerković)—the heroine’s conformity in category romance is implicit; every step toward feminine beauty ideals takes her closer to her happy ending. One example is Bought: The Greek’s Baby, in which the heroine was never seen without lipstick before the pregnancy (22-23), and the hero is sure that “[j]ust the thought of losing her figure and not fitting into all her designer clothes must have made her crazy” (26). But losing her memory after an accident allows her “true” self to surface, which changes her provocative wardrobe into “pink cotton dress[es]” (153), and rewards her with the love of the hero.

More than anything else, though, it is what the pregnancy signifies that is attractive to the male hero. This is made the most explicit in Monroe’s His Royal Love-Child, in which Marcello experiences “pride in his accomplishment” (131) and the woman’s role in a pregnancy is described as entirely passive. Danette says, “I didn’t get myself pregnant” (135), despite the fact that she was aware that they were having unprotected sex and assumed that he was the one not conscious of it, and he agrees, “No, amante. I did that” (135, emphasis in original). Her pregnancy puts him into a “territorial mood” (142) and he makes it clear to her that she carries his child in her body (120). This conflation of the baby and property is a repeat of the hero’s earlier desire to ensure custody of the child because he considers himself the owner while the mother is merely the vessel and is, if not a good candidate for the mother-role, expendable. This is made explicit at an earlier point in the same novel when the heroine realizes that “the man really, desperately, wanted the baby in her womb, but it had nothing to do with her being the mother” (emphasis in the original, 99).

Other scholars who examined the ways in which pregnancy is treated in the public sphere have noted that pregnant women are now “more susceptible to public surveillance” (Hefferman et al. 322). Drawing on studies by Robyn Longhurst, Jane M. Ussher, Susan Markens, and C.H. Browner, Kristin Hefferman et al. conclude that—because the pregnant body is considered “a ‘container’ for the foetus”—everything the mother does or decides has to be considerate of the baby, in order “to avoid being labeled as a ‘bad’ mother” (322). This split between the pregnant woman and her fetus is particularly noteworthy, as it explains why the Harlequin heroine is so often forced to prove that she is a good mother if she wants to remain a part of her child’s life, particularly in the pregnancy revenge narratives discussed earlier. Marriage without love is a legality in which the baby receives the hero’s name, thereby allowing him to claim ownership of the child. For the mother, marriage is a means to give the baby financial security and the stability that, it is explained through the heroine’s own unhappy upbringing, only a traditional family model can provide.

The hero’s agreement to or proposal of a marriage of convenience, however, does not mean that she is recognized as a good mother, merely that she consents to his control in exchange for his function as father. She first has to prove her worth before the economic [End Page 11] agreement can be transformed into a marriage of love. A similar use of pregnancy as a device for transformation has been noticed in Hollywood films by Oliver, who explains that “pregnancy has become a metaphor for other types of transformations” (8). In romantic comedies, it “is the means through which both the male and female characters grow and mature as individuals, and thereby become suitable partners and parents” (9-10). The Harlequin heroine does not always have to prove her worth as a mother; yet, she ultimately always proves that she is worthy of the hero’s love and that the marriage of convenience is more than a mere business arrangement. The hero is likewise transformed through her pregnancy and has, by the end, “been forced to acknowledge his own sexism and has resolved to change his behavior,” a conclusion that Vivanco argues is representative of the “Presents” line in general (1068).

Although the pregnancy appears to be the main focus in these Harlequin narratives, it is a mere plot device, with the baby functioning as the connecting point that keeps the two characters together despite their conflicts and misperceptions. For the sake of the baby, the heroine marries the hero. Sometimes that means having to fit into her husband’s household as well, most likely if her husband is of royal blood. Having to do so enables the heroine to realize that what she had been afraid of all along was her feelings of love for the hero. Along similar lines, Parley Ann Boswell notes that pregnancies are often “used as plot devices, tropes, and deus ex machina” (9), because “our recognition of pregnancy allows it, once introduced into a plot, to morph nimbly and become almost anything from a whispered word, to an abstract idea, to a visual image, to a consumable good” (10). That said, the nature or character of a good marriage is often discussed in these texts, as the characters ponder the often-loveless relationship of their own parents and the detrimental effect it had on themselves as children. Likewise, the heroine realizes that an economically stable but dispassionate marriage is not enough for her own wellbeing; for instance, Green’s protagonist acknowledges that she might wither and die in this loveless environment (170), and the majority follow the example of Duncan’s heroine and decide to leave the hero after all. The hero’s reaction to her decision falls into one of two categories: he has either fallen in love with her in the course of their short marriage and now has to convince her of his feelings, or the threat of losing her makes him realize that what he has been feeling for her is indeed love.

This brings me to the question: What happens to the heroine’s job? Only a few novels discuss her career aspirations. In Kate Hewitt’s The Marakaios Baby (2015), Margo gives her career as a reason for not marrying Leo, explaining that she does not want to be a housewife for fear of being bored, and Keira in Pirate Tycoon, Forbidden Baby is indignant when told that being pregnant is her new job. In all cases, the plot drives the transition from working woman to mother. The marriage because of her pregnancy nullifies all previous conversations about the incompatibility of marriage and the heroine’s independence, because it is now not merely herself she has to care for. In the case of a royal wedding, the heroine has no choice but to take up wifely duties as she will become the new queen—the press also often makes it impossible for the heroine to return to her job, as Leila has to find out when her perfume shop is overrun by the media. Leo and King Alix Saint Croix give their wives an opportunity to work, Leo by providing her with a job in his office and King Alix by presenting his perfume-maker wife with a factory in which she can produce new scents. In both cases, it is only with his help that she can resume work, and in neither is it treated as a potential career. [End Page 12]

Without fail, the transformation into a housewife ultimately makes the heroine of the pregnancy narrative happy. The Princess of Surhaadi finds fulfillment in her family and Eve, the heiress and society girl from Bought: The Greek’s Baby, excels in her role as mother of three while juggling social affairs. The heroines do not need a career to find happiness. The hero exists, so Talos tells his wife in Lucas’s novel, “to satisfy [her] every desire” (146). Along similar lines, Leo argues that he is “not expecting [her] to have duties” around the house; she can do as much or as little as she wants, and being his wife offers her “freedom, not a burden” (Hewitt 95). In all cases, the heroine finds fulfillment through a pregnancy that was unplanned. Becoming a mother had not been part of her plan to lead a happy life, and as such, the pregnancy narrative presents the reader with the “insight” that babies will make her happy, even if she had not considered having one at all or at this stage in her life. The heroine “has it all” in the end: love, wealth, social status, a family, and the option to work.[10] However, the narrative of the novels suggests that none of this would have been possible without the baby.

The “Harlequin Romance” line, in contrast, focuses more on “relatable women” and does not require alpha male heroes (“Harlequin”). Possibly for that reason, the intersection of career and family is more explicitly discussed in the “Romance” than in the “Presents” imprint. Novels in the “Presents” line that focus on pregnancy usually begin with the demand that the heroine will not work during her pregnancy or the first few years of the child’s life, examples of which would be The Marakaois Baby or Pirate Tycoon, Forbidden Baby. The pregnancy titles in the “Harlequin Romance” imprint, such as Jacki Braun’s Boardroom Baby Surprise (2009), Barbara McMahon’s The Boss’s Little Miracle (2007), or Jessica Hart’s Promoted to Wife and Mother (2008), all indicate that their focus is on parenthood as well as on the workplace. The reason that this imprint is more flexible in its representation of the negotiating of a woman’s career and her ability to be a mother is partially due to the fact that “Harlequin Romance” offers a more equal footing for the relationship that can, as Vivanco observes, often be described with the terms “friends” or “partners” (1078). The following analysis of eight pregnancy-focused titles from 2007-2015 will show, however, that even the pregnancy narratives in this imprint suggest that a woman needs a baby to find fulfillment.[11]

The men in the “Harlequin Romance” pregnancy narrative are often at the center of the story. The heroines do not need to prove to the father that they are good mothers; instead, they need to teach the hero to be in touch with his emotions, to accept support and care, or to realize that a career is not a life, such as in Rebecca Winters’s The Greek’s Tiny Miracle (2014) and Michelle Douglas’s The Secretary’s Secret (2011), as well as her Reunited by a Baby Secret (2015). Yet, as my analysis will show, this imprint offers more flexibility than the “Presents” one, enabling more variety in the scenarios. It can therefore also be the hero who has to show the heroine that there is more to life than a career, as in Gilmore’s The Heiress’s Secret Baby; or that he is a permanent addition to her life and is willing to earn her trust, an example of which would be McMahon’s The Pregnancy Promise (2008).

In contrast to pregnancy narratives in the “Presents” line, the novels do not have to begin with a conflict or a break-up. In several instances, such as in Shepherd’s From Paradise…to Pregnant or McMahon’s The Pregnancy Promise, the characters spend more than a hundred pages—that is, almost half of the book—getting to know each other prior either to having sex or at least to discovering the pregnancy. Once the pregnancy is discovered, the decision to keep the baby is as immediate as it is in the “Presents” imprint and likewise never [End Page 13] doubted, even though some texts mention “alternatives like abortion or adoption” and Marianna, Douglas’s heroine, admits that she had thought about it (Reunited 17).

If abortion as an option is raised, it is done by men, and the heroine makes it clear that it is her choice to have the baby: “He wanted her to get rid of their beautiful baby? Oh, that so wasn’t going to happen!” (Douglas, Secretary 50). Shepherd’s heroine, Zoe, is similarly passionate when the doctor tells her that she has “options”: “‘No.’ Zoe was stunned by the immediacy of her reply. ‘No options. I’m keeping it’” (184). Only “bad” women would truly consider an abortion, as McMahon’s The Pregnancy Promise makes clear via the hero’s traumatized state after his ex-girlfriend, a beautiful but cold supermodel, “aborted the[ir] child because she didn’t want stretch marks marring her skin” (84). Oliver states that Hollywood films employ “the language of choice used by the pro-choice movement” in order to justify “a woman’s ‘right to choose her baby,’ in spite of what others may think” (10). Harlequin avails itself of the same sentiment for its “Romance” pregnancy narratives. Some heroines call it a choice, but even without expressing it as such, the romance heroine is depicted as “choosing” the baby when offered alternatives. Category romance titles that follow this representation thereby promote traditional values by presenting the “choice” to have the baby as the way to happiness and fulfillment, a way the women had not even considered.

While abortion remains a taboo topic, infertility is a recurring theme in “Harlequin Romance” pregnancy narratives. It is often the hero who is unable to have (more) children; the male protagonist in The Heiress’s Secret Baby is infertile due to cancer treatment in his youth and becomes the adoptive father of the heroine’s baby, and Winters’s hero was injured in a bomb attack after his affair with the heroine and she is now carrying the only child he will ever have. Only The Pregnancy Promise features a female protagonist, Lianne, who might not be able to reproduce in the future, as the doctor urges her to have a hysterectomy to save her own health. Despite the fact that Lianne’s time is running out if she wants to have a baby, she opts for finding a man in order to become pregnant rather than turning to reproductive technologies. Except for Lianne, whose timeframe to have a baby is reduced to a few months, the Harlequin heroines do not express any form of “baby hunger” that might drive women to employ medical technologies in order to become pregnant. Lianne, however, represents the threat that a woman’s chance of having a child might slip from her grasp if she waits too long. The reliance on heterosexual sex that produces the baby in all texts, despite the shadow of infertility, reassures the readers that sex and love,[12] not technology, produces children. And most importantly, the shadow of male infertility emphasizes women’s function as producer of future generations; the heroine’s decision to keep the baby secures the future because without her child there would be no babies at all.

As I stated before, the “Romance” imprint is more flexible when it comes to negotiating motherhood and careers. Most pregnancy texts discuss the compatibility of both, as well as women’s options, while ultimately concluding with happiness in the form of a family. However, the family model that is reflected is more modern than the traditional patriarchal type in which the mother’s job is at home. Depending on the narrative—and on the author, as it seems that particular writers favor certain family models—the heroine can keep her company or position as CEO after the birth, as Gilmore’s and Shepherd’s do. In others—Winters’s The Greek’s Tiny Miracle, for example—the heroine gives up her job and does not resume it by the end of the novel. Douglas’s secretary likewise decides to resign from her job and to move back to her hometown, although she has plans to “get a job;” [End Page 14] whether she does so after the conclusion of the novel is up to the reader to decide (Secretary 44). Regardless of the decision the soon-to-be-mother makes, the question of whether a woman can have both a career and a job is always answered with a “yes,” and it is either the hero who assures the heroine that women can have both (Gilmore 99), or she herself explicitly states that she “will organize [her] own life–[her] own house and furniture, not to mention [her] work,” despite being pregnant (Douglas, Reunited 49).

The affirmation that a woman “can have it all” comes, however, with a caveat. The women in these texts all love their jobs; yet, they are often willing to resign in order to raise the child close to their family (Kit in The Secretary’s Secret or Stephanie in The Greek’s Tiny Miracle); they give up a promotion that would mean relocating in order to stay close to the father (Anna in The Boss’s Little Miracle); or they realize that expanding the company will not be possible if they want to be mothers at the same time (Zoe in From Paradise…to Pregnant). Not all women have to make adjustments in their jobs, but if they have a career, they inevitably have to give up something. Polly, the heroine in The Heiress’s Secret Baby, is the CEO of a large department store. This position, however, means that she “was prickly and bossy. She didn’t know the names of half her staff and was rude to and demanding of the ones she did know” (Gilmore 151). Being a CEO requires her to “adjust” after she returns from a month-long vacation and the “cloaks of respectability and responsibility settling back onto her shoulders . . . were a little heavy” (10, 7). The corporate world has no place for human weakness: “So what if she felt as if a steamroller had run her over physically and emotionally before reversing and finishing the job? She wasn’t paid to have feelings or problems or illnesses” (104). It also requires a particular appearance, so that Polly keeps referring to her makeup as “armour” (159).

When Polly learns of her pregnancy she reacts with shock and, while she ties that response to her “need to be a CEO, not a mother” (99), it is motivated by fears about her inability to be a mother because she “can’t bake” (95) and “can’t sew either” (95). The two, motherhood and a career, are not as compatible as it first seemed after all. In order to be a good mother, Polly needs to realize that a career is not a life (170), and to acknowledge that “valuing her independence, her ability to walk away . . . didn’t seem such an achievement anymore” (213). The conclusions across my sample suggest that a woman can have a career, but she needs a baby if she wants to be happy. The necessity of a baby for fulfillment is not the same as being able to “have it all,” seeing that the baby now becomes mandatory for happiness. Furthermore, the fetus always has to come first if one wants to avoid the label “bad” mother: and that includes giving up career opportunities.

Pregnant women in “Harlequin Romance” are financially secure even if they are not CEOs or owners of a company; they do not seek out the father of their child in order to discuss payments. Douglas’s secretary tells the father: “I don’t want anything from you. I assure you I have everything that I need” (Secretary 51). Marion Lennox’s nurse likewise tells the hero, “I can afford [the baby] [and] I didn’t come here for the money” (134), and Marianna in Reunited by a Baby Secret works as a viticulturist and stresses this point: “I work hard and I draw a good salary. It may not be in the same league as what you earn, Ryan, but it’s more than sufficient for both my and the baby’s needs” (Douglas 64). The heroines are also not interested in a marriage of convenience and some are very outspoken in voicing their opinion when the hero mentions marriage for the sake of the child: Marianna asks, “What kind of antiquated notions do you think I harbor?” (Douglas, Reunited 44). Yet, while several texts explicitly state that single women “get pregnant all the time” and that “[n]o one expects [End Page 15] them to get married any more” because “[n]o one thinks it’s shameful or a scandal” (44), all but one of the women contact the father.[13] That is not to say that there are no Harlequin titles in which the heroine decides against contacting or involving the father and instead raises the child alone, as Julia James’s The Greek and the Single Mom from 2010 or Jordan’s A Secret Disgrace from 2012 in the “Presents” imprint demonstrate. However, under consideration here are only narratives that have the pregnancy at the center and James’s, as well as Jordan’s and other single-mom titles, focus on the events after the birth with an actual child present in the storyline.

The majority of the heroines—seven out of eight in my sample—do not expect the father to get involved after they contact him: “I’ll not raise him expecting anything from you. You can walk away” (Lennox 142). However, letting the father know of his new status is portrayed as “the right thing to do” (146), and ultimately always leads to a conventional family by the end of the novel because the hero wants to be a part of his child’s life. Despite the pregnancy novels’ assurance that there is no shame in single motherhood, the happy ending in this particular strand of “Harlequin Romance” publication suggests that the father is a necessary part of finding fulfillment and that forming a family is what good mothers achieve. Some narratives, such as Winters’s The Greek’s Tiny Miracle, explicitly articulate the importance of a child having a father in its life: “[Y]ou’ve known nothing about your own father—not even his name. I can see how devastating that has been for you, which makes it more vital than ever that the baby growing inside you has my name so it can take its rightful place in the world” (107).

As in the “Presents” line, pregnancy in the “Harlequin Romance” functions as a plot device that transforms the two protagonists into suitable partners or good parents. Four novels concentrate on the relationship between the heroine and the hero. The other half feature a hero who needs to learn that being a father and having a family enables him to overcome his own trauma. In these texts, her pregnancy provides a mere vehicle for his transformation from “lone wolf” to father (Douglas, Reunited 47). This is reminiscent of the pregnancy movies of the 1980s and 1990s in which the man was domesticated “at the expense of the pregnant woman, who is used primarily as a backdrop against which the men ‘find’ themselves and learn the true meaning of love and family” (Oliver 41). The fact that male domestication is still a main theme in category romance well after 2000 speaks to the persistent anxiety—and reality—that an unwanted pregnancy will result in single parenthood. Pregnancy in category romance provides a fantasy in which men would rather sue the mothers for custody than abandon their child, and where they turn from cold corporate professionals into caring fathers.

I have shown that Harlequin’s “Presents” and “Romance” imprints both feature a strand of pregnancy narratives that contribute to a particular representation of pregnancy in popular culture. In Hollywood as well as in women’s magazines, pregnancy is represented as women’s “biological destiny” (Sha and Kirkman 365), which is perpetuated by this type of category romance where a woman can have a career, but only a child leads to happiness and fulfillment. Popular culture also strongly polices what makes a “good” mother by heralding certain choices, while punishing those who transgress. In the examined pregnancy narratives, “good” mothers are expected to do everything in their power to give the child a father; their success is then rewarded with love and a family instead of single motherhood. Category romance reflects current discourses on pregnancy and while the narratives examined here allow the articulation of some feminist values (depending on the imprint), it [End Page 16] does so within a patriarchal framework that is ultimately reinforced by the conclusion of the narratives.

[1] I want to thank my anonymous reviewer for bringing Penny Jordan and the titles mentioned here to my attention. I also want to express my gratitude to Eric Selinger for his keen eye for detail and the thoughtful observations he made when reading the draft of this article.

[2] The “Harlequin Romance” series “The Single Mom Diaries,” including texts such as Raye Morgan’s A Daddy for Her Sons (2013), is specifically dedicated to the exploration of single motherhood. “Harlequin Presents” likewise features single mothers, for example in Cathy William’s A Reluctant Wife (2013).

[3] My sample only yielded one narrative that starts out with the female protagonist wanting to have a baby, Barbara McMahon’s The Pregnancy Promise (2008).

[4] Only novels with a title that clearly identify it as a story focusing on pregnancy were counted for this statistic, i.e., titles including the words “pregnancy” or “pregnant,” “baby,” “heir,” “nine months,” “expecting,” or similar. Titles were collected using www.romancewiki.com for publications up to 2012 and www.fictiondb.com for the years 2012-2016.

[5] Cover art used by arrangement with Harlequin Books S.A.® and ™ are trademarks owned by Harlequin Books S.A. or its affiliated companies, used under license.

[6] cf. “The Global Gender Gap Report 2015” by The World Economic Forum or, specifically for North America, “The Gender Wage Pay Gap: 2014” by the Institute for Women’s Policy Research as well as “The Simple Truth About the Gender Pay Gap: Spring Edition 2016” done by The American Association of University Women.

[7] The only notable exception in my sample is The Marakaios Baby, in which fear for the fetus’ survival dominates the pregnancy. Even in this novel, though, the focus remains on the bleeding and the potential miscarriage rather than on concrete discussions of or interactions with the baby growing in her.

[8] Pirate Tycoon, Forbidden Baby has the heroine confined to his islands without access to the internet or a phone, and working is prohibited. In His Royal Love-Child, Danette is taken to Marcello’s island so that she cannot see the tabloids, and Talos, the hero of Bought: The Greek’s Baby, likewise takes his heroine to his island; this time to prevent her from regaining her memory.

[9] Silas Weir Mitchel invented the rest cure in the late nineteenth century as a treatment of hysteria and other nervous illnesses. Mostly used on women, this cure confined the patients to their home and bed and prohibited them from any form of mentally engaging activity, such as writing or reading. Famous patients that suffered this treatment were Charlotte Gilman Perkins, who was put to rest to cure her of postnatal depression, and Virginia Woolf.

[10] Most novels do not tell the reader if the heroine will work again. However, they do not state the opposite either. Presumably, it is up to the imagination of the reader to envision if she will remain a fulltime housewife or return to work.

[11] As before, the selection of Harlequin Romance novels is based on their availability in secondhand bookstores at the time of my research.

[12] In category romance, love and sex are co-dependent. Even if the series focuses on sexual encounters, as “Presents” does, the happy ending retroactively turns the one-night- [End Page 17] stand or sex-focused affair into a fated encounter that ends with marriage, thereby ensuring that women’s sexual liberty is tied to state-sanctioned monogamy after all.

[13] The one woman who does not tell the father is Kit, the heroine in The Secretary’s Secret. She does not inform him because he breaks up with her at the beginning of the novel and pre-empts her hope of becoming a family when he tells her that he does not “do long-term, . . . marriage and babies, and [he] certainly [doesn’t] do happy families” (Douglas, Secretary 15). [End Page 18]

Works Cited

Primary Sources:

Braun, Jackie. Boardroom Baby Surprise. Harlequin, 2009. Harlequin Romance.

Cox, Maggie. The Italian’s Pregnancy Proposal. Harlequin, 2008. Harlequin Presents.

Darcy, Emma. Jack’s Baby. Harlequin, 1997. Harlequin Presents.

—. Ruthless Billionaire, Forbidden Baby. Harlequin, 2009. Harlequin Presents.

Duncan, Tina. Her Secret, His Love-Child. Harlequin, 2010. Harlequin Presents.

Douglas, Michelle. Reunited by a Baby Secret. Harlequin, 2015. Harlequin Romance.

—. The Secretary’s Secret. Harlequin, 2011. Harlequin Romance.

Gilman, Charlotte Perkins. The Yellow Wallpaper & Other Stories. 1892. Dover, 1997.

Gilmore, Jessica. The Heiress’s Secret Baby. Harlequin, 2015. Harlequin Romance.

Goldrick, Emma. Baby Makes Three. Harlequin, 1994. Harlequin Romance.

Green, Abby. An Heir Fit for a King. Harlequin, 2015. Harlequin Presents.

Harris, Lynn Raye. Carrying the Sheikh’s Heir. Harlequin, 2014. Harlequin Presents.

Hart, Jessica. Promoted to Wife and Mother. Harlequin, 2008. Harlequin Romance.

Hewitt, Kate. The Marakaios Baby. Harlequin, 2015. Harlequin Presents.

James, Julia, and Carole Mortimer. An Heir for the Millionaire: The Greek and the Single Mom and The Millionaire’s Contract Bride. Harlequin, 2010. Harlequin Presents.

Jordan, Penny. The Reluctant Surrender. Harlequin, 2010. Harlequin Presents.

—. A Secret Disgrace. Harlequin, 2012. Harlequin Presents.

—. The Sicilian’s Baby Bargain. Harlequin, 2009. Harlequin Presents.

Kenny, Janette. Pirate Tycoon, Forbidden Baby. Harlequin, 2009. Harlequin Presents.

Lee, Miranda. The Secret Love-Child. Harlequin, 2002. Harlequin Presents.

Lennox, Marion. Nine Months to Change His Life. Harlequin, 2014. Harlequin Romance.

Lucas, Jenny. Bought: The Greek’s Baby. Harlequin, 2010. Harlequin Presents.

Marinelli, Carol. Princess’s Secret Baby. Harlequin, 2015. Harlequin Presents.

Marton, Sandra. The Italian Prince’s Pregnant Bride. Harlequin, 2007. Harlequin Presents.

McMahon, Barbara. The Boss’s Little Miracle. Harlequin, 2007. Harlequin Romance.

—. The Pregnancy Promise. Harlequin, 2008. Harlequin Romance.

Monroe, Lucy. His Royal Love-Child. Harlequin, 2006. Harlequin Presents.

—. One Night Heir. Harlequin, 2013. Harlequin Presents.

—. Pregnancy of Passion. Harlequin, 2006. Harlequin Presents.

Morgan, Raye. A Daddy for Her Sons. Harlequin, 2013. Harlequin Romance.

Morgan, Sarah. One Night…Nine Month Scandal. Harlequin, 2010. Harlequin Presents.

Shepherd, Kandy. From Paradise…to Pregnant. Harlequin, 2015. Harlequin Romance.

Williams, Cathy. A Reluctant Wife. Harlequin, 2013. Harlequin Presents.

Winters, Rebecca. The Greek’s Tiny Miracle. Harlequin, 2014. Harlequin Romance.

Secondary Sources:

Boswell, Parley Ann. Pregnancy in Literature and Film. McFarland, 2014.

“Bump Watch.” US Weekly, 28 Feb. 2016, www.usmagazine.com/tag/bump-watch/. Accessed 13 April 2016.

[End Page 19]

Devereux, Cecily. “‘Chosen Representatives in the Field of Shagging’: Bridget Jones, Britishness, and Reproductive Futurism.” Genre, vol. 46, no. 3, 2013, pp. 213-237.

Dixon, jay. The Romance Fiction of Mills & Boon, 1909-1995. 1999. Routledge, 2016.

“Harlequin Submission Manager.” Harlequin, n.d., harlequin.submittable.com/submit/29561. Accessed 18 March 2016.

Hefferman, Kristin, Paula Nicolson, and Rebekah Fox. “The Next Generation of Pregnant Women: More Freedom in the Public Sphere or just an Illusion?” Journal of Gender Studies, vol. 20, no. 4, 2011, pp. 321-332, doi:10.1080/09589236.2011.617602.

Hine, Gabrielle. “The Changing Shape of Pregnancy in New Zealand Women’s Magazines: 1970-2008.” Feminist Media Studies, vol. 13, no. 4, 2013, pp. 575-592, doi:10.1080/14680777.2012.655757.

Jerković, Selma Veseljević. “‘Because I Deserve It!’ Fashion and Beauty Industries in the Service of Patriarchy: The Tale of Chick-Lit.” Facing the Crises: Anglophone Literature in the Postmodern World, edited by Ljubica Matek and Jasna Poljak Rehlicki, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2014, pp. 147-163.

Kushner, Eve. “Go Forth and Multiply: Pronatalist Imperatives on Film.” Bitch Media, 1 January 2000, bitchmedia.org/article/go-forth-and-multiply. Accessed 9 April 2016.

Longhurst, Robyn. Maternities: Gender, Bodies and Space. Routledge, 2008.

Modleski, Tania. “The Disappearing Act: A Study of Harlequin Romances.” Signs, vol. 5, no. 3, 1980, pp. 435-448. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3173584.

“Natalie Suleman.” Wikipedia, n.d., en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Natalie_Suleman. Accessed 9 April 2016.

Oliver, Kelly. Knock Me Up, Knock Me Down: Images of Pregnancy in Hollywood Films. Columbia University Press, 2012.

Rogers, Dorothy. “Birthmothers and Maternal Identity: The Terms of Relinquishment.” Coming to Life: Philosophies of Pregnancy, Childbirth, and Mothering, edited by Sarah LaChance Adams and Caroline R. Lundquist, Fordham University Press, 2013, pp. 120-138.

Sha, Joy, and Maggie Kirkman. “Shaping Pregnancy: Representations of Pregnant Women in Australian Women’s Magazines.” Australian Feminist Studies, vol. 24, no. 61, 2009, pp. 359-371.

Smith, Janet Farrell. “A Child of One’s Own: A Moral Assessment of Property Concepts of Adoption.” Adoption Matters: Philosophical and Feminist Essays, edited by Sally Haslanger and Charlotte Witt, Cornell University Press, 2005, pp. 112-135.

“The Gender Wage Gap: 2014.” Institute for Women’s Policy Research, iwpr.org/publications/the-gender-wage-gap-2014/. Accessed 16 April 2016.

“The Global Gender Gap Report 2015.” The World Economic Forum, reports.weforum.org/global-gender-gap-report-2015/. Accessed 16 April 2016.

“The Simple Truth about the Gender Pay Gap: Spring Edition 2016.” American Association of University Women, www.aauw.org/research/the-simple-truth-about-the-gender-pay-gap/. Accessed 16 April 2016.

Vivanco, Laura. “Feminism and Early Twenty-First Century Harlequin Mills & Boon Romances.” The Journal of Popular Culture, vol. 45, no. 5, 2012, pp. 1060-1089.

Weisser, Susan Ostrov. The Glass Slipper: Women and Love Stories. Rutgers University Press, 2013.

[End Page 20]