[End Page 1]

In Twilight (2008), heroine Bella’s fantasy sequences repeatedly set out and revise the romance narrative of the ‘Sleeping Beauty’ fairy tale. In particular, these fantasy sequences revise the theme of spectacle in ways that challenge the conception of the feminine adolescent figure as romantic object, a passive spectacle to be scrutinized by a male gaze. Instead, vampire Edward is presented as Bella’s object of desire, and his image is spectacularized, associated with the visual excesses of pattern, lace, and sparkles. This perversion of gendered categories of the image and romance narrative allows for a new set of relations to emerge in which the girl is able to articulate and claim a desiring gaze. In revising this element of the traditional ‘Sleeping Beauty’ narrative, popularized by Charles Perrault (1697) and the Brothers Grimm (1857), Bella claims her fantasy romance scenarios as a rebellion, creating the potential to include other possible modes of ‘doing girlhood,’[1] including the capacity for authorship, protest, dissatisfaction, and the clear articulation of desire and a desiring gaze.

The ‘Sleeping Beauty’ tale is frequently understood by fairy tale scholars like Marcia K. Lieberman and Jack Zipes as a metaphor for the adolescent girl’s acculturation into feminine adulthood signalled by the happy ending resolution of heterosexual romance, marriage, and in some versions, motherhood. Stephanie Meyer’s Twilight novels, and the blockbuster films based on the novels, certainly follow this conservative heteronormative ‘Sleeping Beauty’ resolution. Teen protagonist Bella is ‘awakened’ by her Prince Charming, vampire Edward, they marry, have a baby, and go on to spend eternity together as a family. Like Sleeping Beauty, Bella’s rite-of-passage or ‘awakening’ works towards inducting her into the idealised feminine roles of wife and mother. Several scholars have written about this heteronormative narrative movement in Twilight as retrograde and conservative (Veldman-Genz; Platt; Seifert). However, this paper challenges the simplicity of this reading of Twilight. It deploys a feminist poststructuralist methodology in order to locate points of resistance and innovation in teen film, identifying the ways in which the terrain of girlhood can be expanded to incorporate new and previously unthought-of iterations of power and agency. Chris Weedon writes that the aim of feminist poststructuralism is to ‘understand existing power relations and to identify areas and strategies for change…to explain the working of power on behalf of specific interests and to analyse the opportunities for resistance to it’ (40). I deploy this methodology in the study of this teen screen revision of the fairy tale because it offers a dual optic through which firstly to interrogate and deconstruct the status quo gender relations embedded in and perpetuated by popularised and canonised versions of the fairy tale. Secondly, this optic then works to highlight ruptures and iterations of girls’ resistance, rebellion, and agency in the film’s revision This is a significant theoretical move for both girlhood studies and teen film studies, for, as Alison Jones argues, this feminist poststructuralist methodology becomes ‘part of the process of enlarging the possible discourses on/for girls and thus the range of feminine subject positions available to them in practice. Or, put another way, we can contribute to increasing the number of ways girls can “be”’ (162). The purpose of this article, then, is to identify the ways in which these ruptures can surface on the teen screen, and how Twilight’s Bella resists the status quo and expands feminine adolescence into new territories through fantasy.

It is clear that many scholars have focused on Bella’s narrative journey post-awakening into feminine adulthood. But this teen screen ‘Sleeping Beauty’ text also includes a very significant labouring of this conservative resolution and Bella’s induction [End Page 2] into the strictures of womanhood. As Maria Leavenworth points out, ‘[t]he Twilight saga is not an extended series in the same sense [as a television serial], but it similarly resists closure, and specifically romantic closure, in the first three texts’ (original emphasis 78). In addition to the delay and resistance of closure inherent in the serial format of the text, Twilight’s ‘Sleeping Beauty’ scenes, which focus on Bella’s dreaming and fantasy images of a beautified Edward in particular, dramatically halt narrative development, becoming points of visual and temporal excess which trouble the linear logic of the narrative and the conservative work of closure. It is in this fantasy space that Twilight’s most subversive, rebellious, and resistant moments of ‘doing girlhood’ arise. These points of temporal and visual excess in Bella’s fantasy sequences rupture and reconfigure the gender relations embedded in the earlier ‘Sleeping Beauty’ text, and this rupture provides space for new positions for the girl heroine to adopt in the romance narrative.

The Twilight series certainly participates in postfeminist cultural ideals about femininity, particularly through the paradigm of ‘active hero/passive heroine’ (Taylor 34), a return to domesticity via the glorification of marriage and motherhood (Negra 47; Renold and Ringrose 329), and the obliteration of personal independence in favour of romantic connection (Gill 218; McRobbie 543). However, this paper shows that this postfeminist ideal of girlhood and feminine acculturation is also significantly challenged, interrupted, and even rejected at times during Bella’s ‘Sleeping Beauty’ fantasy and dream sequences. With a particular focus on the fantasy and dream sequences that especially proliferate throughout the film text Twilight, I argue that Bella productively disrupts the discourse of feminine beauty and desirability, which requires girls to silence their own desire whilst simultaneously presenting a desirable image for a heterosexual male gaze.[2] I therefore consider this unruly fantasy element of the romance, which challenges and ruptures discourses that seek to govern girlhood through sexist power structures, central to a feminist reading of the text.

Twilight’s unruly fantasy elements, which test these sexist structures and gendered boundaries, include an articulation of gender rebellion. Moments of gender rebellion are significant to note because they work ‘against emphasised femininity, a discourse that reinforces women’s subordination to men’ (Kelly et al. 22). These moments are, as Jessica Laureltree Willis points out, ones in which girls can ‘invent and invert notions of gender’ (101). Willis further writes that using ‘imagination as a resource’ is one way in which girls exercise agency because it is here that they can find ‘spaces for manoeuvring within cultural possibilities for re-conceptualising notions of gender’ (109). In the fantasy sequences presented from Bella’s point of view, Bella temporarily rejects a central stricture that seeks to define and delimit girlhood: the discourse that places the girl as object of heterosexual masculine desire. Bella’s rejection of this stricture defies the paradigm of feminine passivity and submission that pervades the Perrault and Grimm versions of the ‘Sleeping Beauty’ tale. These fantasy sequences not only significantly revise the gender dynamics of the fairy tale, but also provide an expansive imaginative space through which Bella explores new and potentially empowering ways of ‘doing girlhood’ and engaging with romance.

Elizabeth Cowie’s theorisation of fantasy is immensely useful for my reading of Twilight. In her psychoanalytic account of cinematic fantasy, Cowie argues that it ‘involves, is characterised by, not the achievement of desired objects, but the arranging of, a setting out of, desire; a veritable mise-en-scene of desire…The fantasy depends not on particular [End Page 3] objects, but on their setting out and the pleasure of fantasy lies in the setting out, not in the having of objects’ (159). She goes on to suggest that in such a setting out, the spectator is presented with ‘a varying of subject positions so that the subject takes up more than one position and thus is not fixed’ (160).[3] Fantasy may therefore provide a significant challenge and rupture to cultural discourses that seek to fix, stabilise, normalise, and restrict girlhood, as it is a practice of setting out and exploring multiple possibilities for being in the world. Furthermore, it provides a method for theorizing girls and girlhood (both for the girl in the film’s diegesis, and the ideal girl spectator that the text addresses) as active and in flux rather than as fixed and static categories. This variability of objects, positions, and ‘settings out’ provides an invitation to explore multiple, contradictory, and perhaps challenging new ways of doing girlhood. In Twilight, Bella designs fantasy sequences in which possible modes of femininity that fall outside of the definitional boundaries of ‘good’ girlhood can be engaged. This reconfigures gendered relations in fantasy, affording the heroine a position from which to articulate her desire and enact a desiring gaze. In this way, Bella’s fantasy sequences are a setting out, an invitation to spectatorial identification with a teen girl gaze and desire.

The exploration of ‘alternative universes’ in which the normative rules that seek to define and delimit girlhood according to the requirements of patriarchal culture can be broken is central to the genres of girls’ fantasy (Blackford 3). Bella’s alternative fantasy universe, which she constructs in the privacy of her own bedroom, includes the breaking of several normative rules that govern girlhood, replacing them with more agentic possibilities for girlhood. Instead of submitting to the notion that girls have little or no control over the processes of their rite of passage, Bella creates a fantasy space that she has authored and designed. This provides a significant opening for reconfiguring her experience of girlhood in order to include new and potentially empowering elements. Spectatorial engagement with this fantasy could therefore mean an engagement with these new articulations of girlhood, providing an opportunity to fantasise about doing girlhood differently. Indeed, Willis argues that media representations of ‘female agency…located within the imaginary realm’ can provide ‘alternate perspectives on gender and subjectivity’ and thus offer readers and spectators ‘spaces in which girls are not bound by the normative rules or roles of a society’ (106-7).

The potential for this space to act as an invitation to fantasy is important for theorising an active teen spectatorial position. In her work on soap opera spectatorship, Ien Ang writes that

‘the pleasure of fantasy lies in its offering the subject an opportunity to take up positions which she could not assume in real life: through fantasy she can move beyond the structural constraints of everyday life and explore other, more desirable situations, identities, lives. In this respect, it is unimportant whether these imaginary scenarios are “realistic” or not: the appeal of fantasy lies precisely in that it can create imagined worlds which can take us beyond what is possible in the “real” world’ (93).

She concludes that ‘[f]antasy and fiction, then, are safe spaces of excess in the interstices of ordered social life where one has to keep oneself strategically under control’ (95). Ang’s theorisation of spectatorial engagement with fantasy provides a way of reading Twilight’s [End Page 4] invitation to identification. Bella’s fantasy ‘Sleeping Beauty’ scenarios, which ‘move beyond the structural constraints’ that govern and keep girlhood ‘under control,’ provide an invitation to spectatorial engagement with an imaginary world in which those governing forces have been replaced with alternative, perhaps more desirable, positions and possibilities for feminine adolescence and for engaging in romance narratives.

The romance narrative of the ‘Sleeping Beauty’ fairy tale has been vigorously critiqued by feminist scholars, who point out the sexist dynamic of feminine adolescent passivity and masculine dominance that the tale represents and even promotes.[4] In its culturally pervasive Perrault and Grimm versions, the tale hinges on an encounter between feminine beauty and passivity which is represented as essential to being desirable, and an active, dominating male prince. This encounter places the unmoving and unconscious girl at the centre of a scene of spectacle, upholding sexist structures of the gendered image and gaze. Indeed, feminist scholars like Rowe, Lieberman, and Kolbenschlag have pointed out that this privileging of feminine glamour and passivity reflects the expectations and restrictions placed on girls and women in contemporary culture. This research revealed how the tale upholds the patriarchal script of feminine passivity and subservience to masculine authority, and furthermore, that the tale shrouds this disturbing script in the guise of romantic love between the prince and princess. Twilight both participates in and yet significantly challenges this tradition to create opportunities for subversive revisions of ‘Sleeping Beauty’s’ sexist gender dynamic.

Feminine passivity seems to be embedded in the rite of passage of the ‘Sleeping Beauty’ tradition. In the anonymous fourteenth century telling of the tale, the romance Perceforest and Giambattista Basile’s version of the tale, ‘Sun, Moon and Talia’ (1634), the prince rapes and impregnates the princess as she lies in her enchanted comatose state, inducting her (unwillingly) into the role of mother. While Perrault and the Grimms removed this extreme violation in their more culturally pervasive versions of the tale, the sexist paradigm of feminine passivity versus masculine dominance remains in the narrative of the helpless maiden and the brave, active prince. When the heroine awakes from her slumber and completes her rite-of-passage into womanhood, she is promptly installed in the roles of wife and mother. Lieberman writes that ‘since the heroines are chosen for their beauty…not for anything they do…they seem to exist passively until they are seen by the hero, or described to him. They wait, are chosen, and are rewarded’ with marriage (189). Lieberman elaborates that in this extreme passivity, the heroine has only her beauty to offer, which is most often represented in the tale as ‘a girl’s most valuable asset, perhaps her only valuable asset’ (188). In both the Perrault and Grimm versions, the authors describe the figure of Sleeping Beauty as pure spectacle. Perrault describes the scene of the prince’s discovery in terms that highlight and spectacularize passive feminine beauty: ‘he entered a chamber completely covered with gold and saw the most lovely sight he had ever looked upon – there on a bed with the curtains open on each side was a princess who seemed to be about fifteen or sixteen and whose radiant charms gave her an appearance that was luminous and supernatural’ (691). The scene is described in opulent extravagance, with the girl’s figure set in a room studded with gold, laying in a bed with the curtains suggestively thrown open. Fixed in her comatose state, the girl functions here as passive spectacle, ‘the most lovely sight,’ for the prince’s pleasure.

Feminist film and cultural criticism is similarly centrally concerned with the sexist dynamics that construct woman as passive spectacle for a determining male gaze, and the [End Page 5] ways in which they are played out and reproduced in the cinema (Mulvey). Sandra Lee Bartky elaborates that the scrutiny of the gaze functions as a disciplinary force which ensures that ‘[n]ormative femininity [comes] more and more to be centred on woman’s body…it’s presumed heterosexuality and its appearance’ (80). This gaze becomes so culturally pervasive that ‘the disciplinary power that inscribes femininity in the female body is everywhere and nowhere; the disciplinarian is everyone and yet no one in particular’ (74). Significantly, the girl is not only compelled to make herself available as spectacle for this gaze; she is also required to internalise it, resulting in self-surveillance and self-discipline practices that work to ensure the girl’s position as object (for example, in beauty product and diet discourses). This gaze therefore works as a profound disciplinary force, involved in the maintenance of gendered power relations in which girls and women not only present themselves as passive objects of the gaze, but also view and therefore define themselves through it.

Also central to this construction of girlhood as passivity is the lack of cultural acceptability around girls expressing their desires. Indeed, girlhood studies scholar Marnina Gonick writes that for a girl to be considered ‘good’ ‘usually means that a girl’s desire is left unspoken or spoken only in whispers,’ silencing ‘what has traditionally been socially and culturally forbidden to girls: anger, desire for power, and control over one’s life’ (64 -65). For Deborah Martin, this silencing of girls’ desire in cultural constructions of girlhood reflects ‘the requirements of patriarchal culture for the young girl to give up active and agentic desire and accept her status as object of desire’ (137). These are ‘highly restrictive and regulatory discourses’ that work to contain girlhood (Renold and Ringrose 314) and the possibilities of what it is acceptable to express from the subject position of teen girl. In the ‘Sleeping Beauty’ tale, it is both the spectacularization of the girl’s figure and her inability to direct the course of her own rite-of-passage that not only places her in the position of passive waiting, but also robs her of the opportunity to articulate her own desire.

Twilight provides a significant revision of the earlier text’s construction of feminine adolescent desire because it is central and authoritative, rather than marginalised and silenced. Bella reconceptualises both the elements of spectacle in her romance fantasy ‘Sleeping Beauty’ sequences in ways that are resistant to the literary fairy tale’s construction of girlhood-as-passivity. Bella’s fantasy designs of her ‘prince’ Edward’s image contain spectacular and pretty elements, challenging the tale’s gendered visual economy that privileges the prince’s controlling masculine gaze and the heroine’s passive glamour. This spectacularization of Edward reverses the gendered dynamics of the tale, placing him in the position of ‘Beauty.’ In this reversal, Bella is able to claim a measure of agency and active looking that the heroine of Perrault and the Grimm tales could not. Bella creates a fantasy space in which she can reject the normative construction of femininity that demands that girls present themselves as desirable objects for a determining masculine gaze. These points of excess in the construction of the representation of romance not only challenge the structures designed to keep the heroine in a passive position; they also work to create new meanings in the ‘Sleeping Beauty’ romance, and create new possibilities for representing girlhood in potentially empowering ways.

Cinematic spectacle and prettiness contain the disruptive potential of excess, and Bella’s spectacular and pretty fantasy images of Edward reconfigure the gendered politics of the image and the gaze. Interestingly, it is this spectacular aesthetic of the Twilight films [End Page 6] that some scholars have labelled as potentially harmful and seductive to a teen girl audience.[5] Natalie Wilson, for example, writes that Twilight acts as a powerful ‘drug’ for unsuspecting female fans, who become ‘prisoners to its allure’ (6). Only those who maintain the ‘critical distance’ of ‘mocking’ and ‘resisting’ the films’ spectacular romantic excesses (6-7) can succeed in refusing the harmful ‘seductive message’ of fulfilment through true love and romance with a Prince Charming that Twilight narrativises (8). Margaret Kramar similarly laments, ‘[u]nfortunately, modern teenagers…may not be able to extricate themselves from Bella’s mind-set or question her underlying assumptions analytically’ (26). I challenge this suspicion and derision of spectacle in Twilight, finding that spectacle is one of its most subversive and critical elements in its representation of contemporary romance and girlhood.

Wilson and Kramar’s assertion that a productive reading of the text only emerges in the cold, distant manner that opposes and scorns the image not only participates in a sexist aesthetic hierarchy of suspicion and degradation of feminine spectacle and prizing of masculine austerity and distance, but also misses the rich potential for the spectacular and pretty teen screen image to be politically potent and invested with details that significantly disrupt the conservative narrative flow. Such a reading is productive for a feminist perspective on the cinematic text, for, as Rosalind Galt writes, a consideration of the pretty considers ‘how the image is gendered formally and how thematic iterations of gender in film can be read not just against women’s historical conditions, but against the gendered aesthetics of cinema itself’ (255). Engaging spectacle and the pretty in a reading of Twilight reveals the way in which the excesses of these elements not only undermine the conservative ideology of the narrative flow, but also work to create a new set of gendered romantic relations through the image and the gaze. In this new set of relations, Bella claims authorial control over the spectacular design of her fantasy image of Edward, providing her with an opportunity to claim and sustain a desiring gaze.

Bella’s fantasy sequences, which revise the gendered dynamics of the Perrault and Grimm ‘Sleeping Beauty’ tales primarily occur in Bella’s bedroom. In these romantic fantasies, Bella is able to construct a bedroom culture that is enabling and productive. Anita Harris suggests that bedroom culture can function as a kind of ‘retreat,’ which can productively be read as ‘an active choice on the part of young women refusing to participate in particular constructions of girlhood’ (133). Harris elaborates, ‘the scrutiny of young women remains…and it is this scrutiny that forces them into private places to reflect and resist’ (133). The bedroom culture that Bella authors and designs in the fantasy realm is indeed a resistant space, where the construction of girlhood as desirability without desire is thoroughly undermined. It is in this enabling and productive bedroom culture that Bella situates and authors fantasy ‘Sleeping Beauty’ scenes. Instead of accepting her role as passive object for the scrutiny Harris describes, she chooses to design fantasy romance scenarios in which she can clearly articulate her desire and claim a desiring point of view.

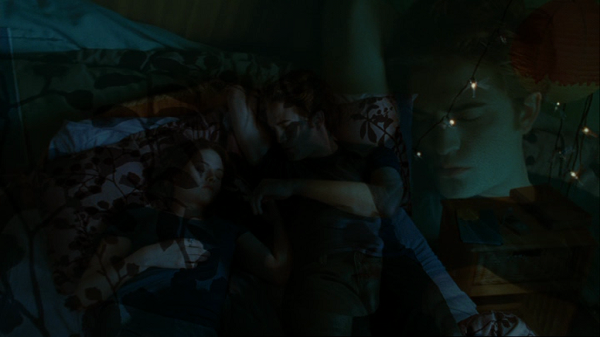

Bella’s authorial control over the fantasy sequences is made clear in the beginning of one sequence in Twilight, which presents the scene on a black and white filmstrip that moves across the screen. The soundtrack is dominated by the clicking and whirring of the film running through a projection machine, further emphasising themes of production and projection. [End Page 7]

This establishes Bella’s ‘Sleeping Beauty’ fantasy – a romantic embrace between the reclining Bella and vampire Edward – as a kind of film within the film, a scene that she has constructed, written, directed, and projected. This scene unfolds according to Bella’s fantasy design, where she has carefully set out her longed-for objects within the mise-en-scene of her desire. This clearly establishes Bella’s authorial authority over the fantasy sequence. As the work of scholars like Gonick and Martin shows, ‘good’ girlhood is governed by an interdiction against girls expressing their own desire and claiming a desiring and authoritative point of view, in order for them to be securely placed in the role of object of desire and scrutiny. Bella’s fantasy sequences, however, create an alternative universe in which this construction of girlhood is thoroughly subverted. Bella authors scenarios and images of her own design, which not only subvert the scrutiny girls are placed under, but creates in its stead a clear position from which to enact a desiring gaze and to articulate her desire.

Twilight’s ‘Sleeping Beauty’ scenes, which focus on Bella’s dreaming and fantasy images of a beautified Edward, dramatically halt narrative development, becoming points of both visual and temporal excess that rupture the logic of the earlier fairy tale text. In the Perrault and Grimm versions of the tale, the heroine’s sleep represents her complete vulnerability and passivity to the prince’s advances, gaze, and, in Basile’s version, the horrific rape. In Twilight, Bella creatively pursues new ‘Sleeping Beauty’ fantasies that halt the narrative of feminine acculturation and instead insistently focus on her enjoyment of gazing at Edward, significantly reversing the gender dynamics of the earlier text. In these bedroom scenes, there is an intense focus on sleep and dreaming, and a heavy-handed deployment of filmic techniques like slow motion, ultra-slow dissolves, and slowly spiralling camera movements. At the beginning of one of these scenes, Edward and Bella move towards one another and kiss at a painstakingly slow place. This lingering on the [End Page 8] incremental, and almost barely perceptible movement stops the narrative in its tracks. The soundtrack punctuates this languor with the couple’s slow, rhythmic inhalations and exhalations. In the following sequence of the scene, there is a transition of shots between a medium and close-up shot of Edward and Bella asleep. The ultra-slow dissolve settles on the scene like a fine mist.

As this dissolve occurs, the transition between images creates a decorative image in which the figures are decorated with superimposed golden firefly fairy lights and the embellished floral design of Bella’s bedspread. The camera spirals in on the two figures very slowly as this gradual transition between shots occurs, creating a dreamy, hypnotic slowing down and reduction of time. A decorative image is created both by the mise-en-scene’s decorative elements as well as the elaborate editing techniques, suspending narrative and focusing attention on Bella’s fantasy moment of enjoying Edward. This scene of Bella and Edward sleeping is protracted through the use of the ultra-slow dissolve and the dreamy spiralling movement of the camera. As opposed to the determining forces of logic, linearity, and progress, delay provides indeterminate time. Bella’s purposeful slowing-down of time in her fantasy sequences refuses to accommodate the roles and responsibilities of impending womanhood. While the heroine of the Perrault and Grimm versions of ‘Sleeping Beauty’ is imprisoned and made vulnerable by her slumber, Bella’s fantasies of delay are ruled by her expressions of desire, her enjoyment of Edward – and the defiantly intense focus of her attention on these pleasures. This significantly contributes to Twilight’s revision of the passivity and helplessness embedded in the earlier versions of the ‘Sleeping Beauty’ tale. Bella actively constructs these points of temporal and visual excess through her fantasies, significantly interjecting a time that is not ruled by these processes and expectations. This use of slow-motion techniques therefore performs a critical function because it troubles the [End Page 9] seemingly ‘natural’ smooth development of the conservative narrative’s progress towards Bella’s feminine acculturation, and also suggests a desire to rupture this progress and thus an ambivalence and dissatisfaction towards the feminine rite of passage itself.

In these fantasy moments, Bella is temporarily relieved of this construction of time that works to contain and control the progression of girlhood into an idealised womanhood (Lesko; Walkerdine). Girlhood studies scholar Valerie Walkerdine elaborates the specificity of time for feminine adolescence. She writes that girlhood is represented as a period of ‘preparation for the prince’ in both fairy tales and girls’ literature (97). The point of resolution, the prince’s arrival, is ‘attractive precisely because it is the getting and keeping of the man which in a very basic and crucial way establishes that the girl is “good enough”…It is because getting a man is identified as a central resolution to problems of female desire that it acts so powerfully’ (99). This temporality constructs passive progress towards idealised feminine adulthood, which continues to be at least in part defined by romantic ideologies, heterosexual partnership, and motherhood. Interestingly, though the Twilight series’ narrative works towards this resolution that Walkerdine describes, its forestalling techniques consistently frustrate, refuse, and defy its fulfilment. Both the seriality of the Twilight texts and the deployment of filmic techniques such as slow motion and the slow dissolve in the fantasy sequences work to disrupt linearity, defer progress, and challenge narrative cohesion. Bella’s ‘Sleeping Beauty’ fantasy sequences not only challenge but also unravel these forces that seek to govern, define, and delimit ‘acceptable’ or ‘normal’ girlhood. The temporary unravelling of these borders allows the fantasy sequences to incorporate other, potentially disruptive iterations of girlhood.

The spectacular excess of Bella’s fabrication of Edward reconfigures the gendered norms of the gaze and desire. In her ‘Sleeping Beauty’ fantasy sequences, Bella is not coded as the ‘Beauty’: Edward, the glittering, perfectly groomed, alabaster-skinned eternal teenager is. In these scenes, and indeed throughout the film series, Edward’s figure is repeatedly associated with sparkles, lace, shimmering light, soft skin, and immaculately coiffed hair. In one ‘Sleeping Beauty’ fantasy scene in Twilight, Bella dreams that Edward is in her bedroom. Edward’s face is framed in extreme close-up. He is bathed in a golden, shimmering moonlight that shines in through the window. This moonlight shines through a lace curtain, which creates a dramatic dappled frill pattern of light and shade across Edward’s glowing skin. [End Page 10]

This fantasy moment associates Edward’s figure with these elements of visual and decorative spectacle. The supplemental nature of the decorative, its very gratuitousness, is troublesome, because it exceeds the requirements of the narrative and potentially disrupts its ideology.

These spectacular textural details disrupt the gendered politics that govern girlhood and the gaze. Laura Mulvey’s famous argument that the male figure onscreen cannot ‘bear the burden of objectification’ (13) is challenged in Twilight’s construction of Edward as an extravagantly shimmering spectacle. Spectacular cinematic images have political potential because they have the capacity, in their excess, to rub up against and potentially erode the conservative ideology that the narrative works to hold in place. Barbara Klinger’s work on Douglas Sirk’s melodramas argues that the deployment of an excessive or unreal mise-en-scene can work to ‘subvert the system [of representation] and its ideology from within’ (14). Jane Gaines, in her work on the textural excesses of costume in classical Hollywood cinema, similarly argues that these elements have the capacity to become a ‘dissonant detail’ (150) in the text that is resistant to, in excess of, and uncontained by the ‘conservative’ narrative flow. Kay Dickinson similarly writes that one cinematic component may ‘radically contradict’ another, and that such a contradiction of a conservative narrative or image may defy, challenge, and even overwhelm it (15). Dickinson sees this challenge at work in the text as potentially ‘not only an intrinsic property, but also…a political tool at work within both the object of analysis itself and its audience’s active perception’ (19). These moments of visual spectacle can therefore be seen as having political potency and potential as it not only challenges the normative ideology of the narrative, but also prompts a similarly unruly response from the spectator.

The spectacular aesthetic that Bella creates significantly challenges the immense scrutiny that girls and women are placed under – it enacts the ‘radical contradiction’ that [End Page 11] Dickinson argues for. This is significant because, as Susan Bordo argues, the ‘grip’ of controlling surveillance and scrutiny is one of contemporary culture’s ways of regulating, monitoring, and manipulating the female body ‘as an absolutely central strategy in the maintenance of power relations between the sexes’ (76-77). Currie et al. similarly show that a ‘dominant way to do girlhood’ is ‘the performance of…“emphasised femininity”: the practice of heterosexual femininity that is “oriented to accommodating the interests and desires of men” and thus to reconstituting women’s subordination’ (94). Bella’s fantasy sequences challenge the visual structures that hold this subordination in place by designing a visual economy in which she can evade this scrutiny and instead take up an active desiring position in the context of her self-authored romantic fantasies.

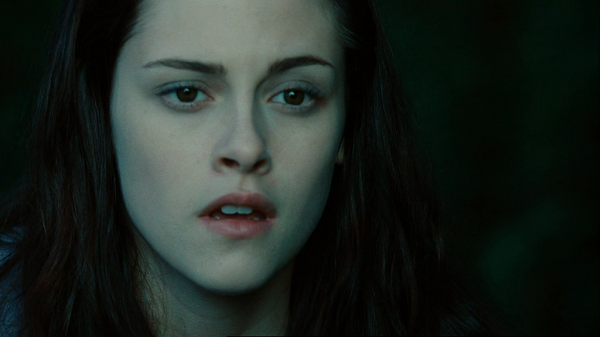

In these fantasy moments of visual spectacle, the conservative trajectory of the narrative is significantly halted in its tracks by the iridescent glittering excess of Edward’s beautiful image and Bella’s enjoyment of that image. The spectacle of Edward’s glittering, luminous skin challenges the gendered politics of the image and the gaze. The first time Edward reveals his sparkling skin, these gendered politics of image and gaze are revised, creating a significant invitation for the heroine to enact a desiring look. Edward and Bella are in the forest, and Edward stands in the sunlight, revealing that it is the reaction of light and vampire skin that creates this glittering effect. Edward unbuttons his coat and shirt as he stands in this spotlight of sunshine, and his face and torso light up with the lustrous shimmer of thousands of tiny diamonds. The scene then cuts to Bella’s face in close-up as she admires Edward’s pretty sparkling display.

Bella exclaims ‘you’re beautiful!’ as the camera cuts to her point of view and slowly pans up his torso, lingering on this spectacle. [End Page 12]

This visual display of the male figure’s prettiness for the heroine perverts the sexist structures of the gaze which fix the female figure in the role of passive spectacle and assert the control of the male figure. It is Edward’s figure that is aligned with spectacle and the over-the-top design of glamorous decoration, and it is Bella who actively enjoys this display – indeed, she calls him ‘beautiful’. Such a perversion of gendered categories carves out a space for a new set of relations to emerge through the image. [End Page 13]

In this way, Bella’s construction of Edward as romantic object and spectacle significantly troubles and reconfigures the gendered politics of the image and the gendered gaze. This provides a challenge to sexist structures of looking, and works to create an opening for a new set of relations in which the heroine’s authorial perspective and desiring look determine the mise-en-scene. This fantasy visualisation is discordant and disruptive. Gaines writes that such visual and aesthetic disruption can create an ‘opening for considering how the spectacular…makes imaginative appeals’ to the spectator and constructs an ‘invitation to…fantasy’ (142-143). These scenes provide an invitation to engage in a fantasy where such a spectacular reconfiguration of gendered dynamics of image and gaze is possible, and where a teen girl gaze can be held as a sustained spectatorial position. Therefore, Bella’s spectacular designs carve out a fantasy space in which spectatorial identification with a desiring teen girl gaze is possible. Such an engagement in fantasy creates an ‘imaginative appeal,’ as Gaines suggests, to consider girlhood in new ways, compelling the spectator to identify with Bella’s challenging and subversive ways of doing girlhood.

Bella is therefore afforded a space in which she can both protest against normative structures of girlhood and romance scripts, then creatively innovate new and potentially empowering positions, expanding the terrain of what is possible for girlhood to include. An examination of fantasy and spectacle is therefore immensely important to a productive feminist reading of the Twilight film texts, as it is here that the most subversive and challenging moments of ‘doing girlhood’ arise. Spectacle in fantasy therefore provides not only an opportunity for rebellion against sexist everyday strictures, but also holds immense creative potential for the valuable work of reconfiguring and reimagining gendered relations in romance. An examination of teen screen fantasy may provide a critical space for examining the scope of both rebellion and innovation in the representation of teen rites of passage.

While many scholarly explorations of the Twilight texts have thoroughly examined Bella’s postfeminist and so-called retrograde journey into adult femininity through marriage and motherhood, few have adequately considered the resistant and unruly fantasy elements in the texts that subvert this conservative closure. As Gottschall et al. note, particular popular images and the ways in which they are engaged with by girls can both ‘rupture and reiterate ways of doing girlhood’ (35) and in this process ‘multiple meanings of girlhood seem to be embodied and enacted’ (39). In this way, Gottschall et al. argue that in any particular media or ‘real life’ example, it is possible for ‘markers of conventional girlhood [to be] enabled and constrained in complex ways’ (40). Therefore, through a feminist poststructuralist methodology, I have argued that while Twilight does present potentially conservative representations of girlhood and girls’ romantic rites of passage, it also simultaneously contains unruly and resistant elements that radically contradict this conservatism. Indeed, in fantasy, Bella is able to break down the visual economy that places girls in a position emphasised femininity, a scrutinised spectacle presented for a heterosexual male gaze, and reconfigures the gendered categories of the image, narrative closure, and the gaze. In this way Bella claims a subjective position and desiring gaze within this romance narrative.

Through alterations to the image and temporality of the tale, Bella carves out a new space in the ‘Sleeping Beauty’ narrative determined by her desire. As this paper has shown, this is significant, as cultural ideals of girlhood continue to hold that such expressions of [End Page 14] desire are ‘culturally forbidden to girls’ and that ‘a girl’s desire is left unspoken or spoken only in whispers’ (Gonick 64-5). If the category of ‘girlhood’ translates, as Gonick suggests, into the silencing of desire, then Bella’s fantasy designs that provide an articulation of her desire significantly alter this construction of girlhood and productively expand the potential for girls to claim powerful subjective positions in the contemporary romance narrative. This article has deployed the powerful methodology of feminist poststructuralism, which offers a dual optic to both interrogate and deconstruct the earlier text’s gender ideologies, while also stressing the opportunities for the heroine’s resistance and agency in the contemporary revision of the tale. These ruptures productively aggravate and destabilise the gender ideology at hand, creating new opportunities for representing the girl’s power and agency in the tale.

Bella’s fantasies provide a setting out of an alternative universe of new possibilities, positions, and objects of romantic desire made available for teen girl spectators. This setting out of the image of Edward and the access to a desiring gaze provides an invitation to spectatorial fantasy in which girlhood is not constrained by the everyday structures that govern and define it. The spectator is presented with the imaginative possibility of a desiring position for the teen girl to occupy, and this imaginative possibility is one that allows for a fantasy of doing girlhood differently, in potentially new and oppositional ways. Bella’s fantasy space is therefore not just meaningful within the text itself; it also proposes significant implications for spectatorial fantasy and imaginative possibilities that expand the terrains of girlhood, romance, and girl’s spectatorship. Bella’s fantasy ‘Sleeping Beauty’ scenarios, which move beyond the everyday structures that govern and contain girlhood, provide an invitation to spectatorial identification with an imaginary world in which those governing forces can be opposed and replaced with a girlhood that includes empowering elements such as the expression of authorial and creative control, desire, oppositional rebellion, ambivalence, and an authoritative point-of-view.

[1] The concept of ‘doing girlhood’ was proposed by girlhood studies scholars Currie, Kelly, and Pomerantz, and drew from Judith Butler’s theorisation of ‘doing gender.’ Theorising ‘doing girlhood’ accounts for the expression of girls’ agency, explaining ‘what girls say and do to accomplish girlhood within limits’ (xvii).

[2] Recent girlhood studies scholarship has interrogated this particular aspect of how contemporary girlhood and girl’s sexuality is governed in patriarchal culture. See, for example, the work of Marnina Gonick and Deborah Martin.

[3] While there is not enough space in this paper to fully elaborate the Freudian and Lacanian psychoanalytic background to Cowie’s theorisation of fantasy, it is vital to explore her contention that fantasy is a setting out of possibilities, entry points, identifications, and desires.

[4] Feminist writers who have addressed these concerns in relation to the ‘Sleeping Beauty’ include Marcia K. Lieberman, Francine Prose, Karen E. Rowe, and Jack Zipes.

[5] See Eva Chen’s study of how the romance genre has long been considered an ‘opiate for the masses’, a ‘dope’ for women that lulls them into an ‘illusory acceptance of the status quo’ (30). [End Page 15]

Works Cited

Ang, Ien. Living Room Wars: Rethinking Media Audiences for a Postmodern World. London and New York: Routledge, 1996. Print.

Bartky, Sandra Lee. Femininity and Domination: Studies in the Phenomenology of Oppression. New York and London: Routledge, 1990. Print.

Basile, Giambattista. ‘Sun, Moon, and Talia.’ In: The Great Fairy Tale Tradition: From Straparola and Basile to the Brothers Grimm. Ed. Jack Zipes. New York and London: W.W. Norton and Co, 2001 [1634]. 685-688. Print.

Blackford, Holly Virginia. The Myth of Persephone in Girls’ Fantasy Literature. New York and London: Routledge, 2012. Print.

Bordo, Susan. ‘Anorexia Nervosa: Psychopathology as the Crystallisation of Culture.’ The Philosophical Forum 17.2 (1985): 73-104. Web.

Chen, Eva Y. I. ‘Forms of Pleasure in the Reading of Popular Romance: Psychic and Cultural Dimensions.’ Empowerment versus Oppression: Twenty-First Century Views of Popular Romance Novels. Ed. Sally Goade. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2007. 30-41. Print.

Cowie, Elizabeth. ‘Fantasia.’ The Woman in Question. Ed. Parveen Adams and Elizabeth Cowie. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1990. Print.

Currie, Dawn H., Deirdre M. Kelly, and Shauna Pomerantz. ‘Girl Power’: Girls Reinventing Girlhood. New York: Peter Lang, 2009. Print.

Dickinson, Kay. ‘Music Video and Synaesthetic Possibility.’ Medium Cool: Music Videos from Soundies to Cellphones. Ed. Roger Beebe and Jason Middleton. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2007. Print.

Galt, Rosalind. Pretty: Film and the Decorative Image. New York and Chichester: Columbia University Press, 2011. Print.

Gaines, Jane M. ‘Wanting to Wear Seeing: Gilbert Adrian at MGM.’ Fashion in Film. Ed. Adrienne Munich. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2011. 135-159. Print.

Gill, Rosalind. Gender and the Media. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2007. Print.

Gonick, Marnina. Between Femininities: Ambivalence, Identity, and the Education of Girls. Albany: State University of New York Press, 2003. Print.

Gottschall, Kristina, Susanne Gannon, Jo Lampert, and Kelli McGraw. ‘The Cyndi Lauper Affect: Bodies, Girlhood and Popular Culture.’ Girlhood Studies 6.1 (2013): 30-45. Web.

Grimm, Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm. ‘Briar Rose.’ The Great Fairy Tale Tradition: From Straparola and Basile to the Brothers Grimm. Ed. Jack Zipes. New York and London: W.W. Norton and Co, 2001 [1857]. 696-698. Print.

Hardwicke, Catherine, dir. Twilight. Summit, 2008. DVD.

Harris, Anita. ‘Revisiting Bedroom Culture: New Spaces for Young Women’s Politics.’ Hecate 27.1 (2001): 128-138. Web.

Jones, Alison. ‘Becoming a “Girl”: Post-Structuralist Suggestions for Educational Research.’ Gender and Education 5.2 (1993): 57-66. Web.

Kelly, Deirdre M., Shauna Pomerantz, and Dawn H. Currie. ‘“No Boundaries?” Girls’ Interactive, Online Learning about Femininities.’ Youth Society 38.3 (2006): 3-28. Web.

[End Page 16]

Klinger, Barbara. Melodrama and Meaning: History, Culture, and the Films of Douglas Sirk. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1994. Print.

Kolbenschlag, Madonna. Goodbye Sleeping Beauty: Breaking the Spell of Feminine Myths and Models. Dublin: Arlen House, 1983. Print.

Kramar, Margaret. ‘The Wolf in the Woods: Representations of ‘Little Red Riding Hood’ in Twilight.’ In Bringing Light to Twilight: Perspectives on a Pop Culture Phenomenon. Ed. Giselle Liza Anatol. New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2011. 15-30. Print.

Leavenworth, Maria Lindgren. ‘Variations, Subversions, and Endless Love: Fan Fiction and the Twilight Saga.’ In Bringing Light to Twilight: Perspectives on a Pop Culture Phenomenon. Ed. Giselle Liza Anatol. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011. 69-81. Print.

Lesko, Nancy. ‘Time Matters in Adolescence.’ In Governing the Child in the New Millennium. Eds. Kenneth Hultqvist and Gunilla Dahlberg. New York and London: RoutledgeFalmer, 2001. 35-67. Print.

Lieberman, Marcia K. ‘“Some Day My Prince Will Come”: Female Acculturation through the Fairy Tale.’ Don’t Bet on the Prince: Contemporary Feminist Fairy Tales in North America and England. Ed. Jack Zipes. Aldershot and New York: Gower, 1986. 85-200. Print.

Martin, Deborah. ‘Feminine Adolescence as Uncanny: Masculinity, Haunting and Self-Estrangement.’ Forum for Modern Language Studies 49.2 (2013): 135-144. Web.

McRobbie, Angela. ‘Young Women and Consumer Culture: An Intervention.’ Cultural Studies 22.5 (2008): 531-550. Web.

Meyer, Stephanie. Twilight. London: Atom, 2005. Print.

Mulvey, Laura. ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.’ Screen 16.3 (1975): 6-18. Web.

Negra, Diane. What a Girl Wants: Fantasizing the Reclamation of Self in Postfeminism. London: Routledge, 2009. Print.

Perrault, Charles. ‘Sleeping Beauty.’ The Great Fairy Tale Tradition: From Straparola and Basile to the Brothers Grimm. Ed. Jack Zipes. New York and London: W.W. Norton and Co, 2001 [1697]. 688-695. Print.

Platt, Carrie Anne. ‘Cullen Family Values: Gender and Sexual Politics in the Twilight Series’. Bitten by Twilight: Youth, Media, and the Vampire Franchise. Ed. Melissa A. Click, Jennifer Stevens Aubrey, Elizabeth Behm-Morawits. New York: Peter Lang, 2010. 71-86. Print.

Prose, Francine. ‘Sleeping Beauty.’ Mirror, Mirror on the Wall: Women Writers Explore their Favourite Fairy Tales. Ed. Kate Bernheimer. New York: Anchor, 1998. 283-294. Print.

Renold, Emma and Jessica Ringrose. ‘Regulation and Rupture: Mapping Tween and Teenage Girls’ Resistance to the Heterosexual Matrix.’ Feminist Theory 9 (2008): 313-338. Web.

Rowe, Karen E. ‘Feminism and Fairy Tales.’ In Don’t Bet on the Prince: Contemporary Feminist Fairy Tales in North America and England. Ed. Jack Zipes. Aldershot and New York: Gower, 1986. 209-226. Print.

Seifert, Christine. ‘Bite Me! (Or Don’t)’. Bitch 42. (2009): 23-25. Web.

Taylor, Anthea. ‘“The Urge Towards Love is an Urge Towards (Un)Death”: Romance, Masochistic Desire and Postfeminism in the Twilight Novels.’ International Journal of Cultural Studies 15.31 (2012): 31-46. Web.

[End Page 17]

Veldman-Genz, Carole. ‘Serial Experiments in Popular Culture: The Resignification of Gothic Symbology in Anita Blake Vampire Hunter and the Twilight series’. Bringing Light to Twilight: Perspectives on a Pop Culture Phenomenon. Ed. Giselle Liza Anatol. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011. 43-58. Print.

Walkerdine, Valerie. Schoolgirl Fictions. London and New York: Verso, 1990. Print.

Weedon, Chris. Feminist Practice and Poststructuralist Theory. Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishing, 1997. Print.

Willis, Jessica Laureltree. ‘Girls Reconstructing Gender: Agency, Hybridity and Transformations of “Femininity.”’ Girlhood Studies 2.2 (2009): 96-118. Web.

Wilson, Natalie. Seduced by Twilight: The Allure and Contradictory Messages of the Popular Saga. Jefferson, North Carolina and London: McFarland and Company, 2011. Print.

Zipes, Jack. The Brothers Grimm: From Enchanted Forests to the Modern World. New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2002. Print.

[End Page 18]