In 1915, the Australian poet and journalist C. J. Dennis published a book of verse called The Songs of a Sentimental Bloke. When read in sequence, the verse told a love story about an uncultivated young man, Bill, and his sweetheart, Doreen, who worked in a [End Page 1] Melbourne pickle factory. Though written in verse, the narrative was what we might now call a romantic comedy. Its humor sprang from the fact that Bill was the antithesis of a romantic type, yet he proved himself a hopeless romantic just the same. In the parlance of the day, Bill was an Australian “larrikin.” He was a young rowdy from the city who spent most of his time fighting, gambling, drinking and street-hawking – yet by the end of the narrative he had transformed into a loving husband and family man. Told in the first person by Bill, the work proved enormously popular. It sold prodigiously during the First World War, prompting Dennis to write four spin-off works over the following decade. Over that period, the currency of The Sentimental Bloke (as it became known) grew rather than waned. It became a multi-media phenomenon, comprising a silent film and travelling stage musical, and it was frequently recited on radio and in concert halls.

Crucial to the success of The Sentimental Bloke was the fact that it was a masculine romance. It was a love story expressing heterosexual romantic feeling from a male point of view and in a self-consciously masculine way. As such it touched a cultural nerve. The war and early interwar years were rife with confusion about men’s relationship to women and romance. Australian men had been expected to be warriors during the war, but upon return were expected to transform into caring spouses (Garton). Romantic Hollywood leads such as Rudolph Valentino became celebrities in early interwar Australia, admired for their sophistication and charm (Matthews 4; Teo 2012: 1). At the same time, however, prominent voices such as the bohemian artist and writer, Norman Lindsay, decried romantic love as feminine and marriage as suffocating to men (Forsyth 59). The Bloke helped audiences to navigate these conflicting messages. It insisted that it was possible for a modern Australian man to be romantic without compromising his masculinity, provided he did so in a sufficiently straightforward manner and steered clear of “Yankee” suavity.

The content and reception of The Sentimental Bloke requires us to think more subtly about the relationship between Australian masculinity and romantic sentimentality across the early decades of the 1900s. Chiefly, it requires us to give more credence to Australian men’s interest in certain forms of romantic popular culture, and to masculine constructions of romantic feeling, than most previous scholars have allowed. Yet Australianists are not the only ones who will benefit from contemplating The Sentimental Bloke. In the field of romance studies at large, romantic love is still largely treated as “feminized love,” to borrow Anthony Giddens’ phrase (43). As things stand, the phrases “masculine romance” and “masculine sentimentality” function almost as oxymorons within romance studies – the key exceptions being in a few discussions of homosexual romance (eg. Shuggart and Waggoner 26–7). My hope is that this discussion will prompt romance scholars to take more interest in masculine romance, and to consider in particular how this relationship developed in the war and early interwar years.

The multi-media phenomenon of The Sentimental Bloke

Almost as soon as it hit the bookstores in late 1915, it was apparent that The Songs of a Sentimental Bloke (later shortened to The Sentimental Bloke) held a powerful popular appeal. Dennis had engaged in canny publicity for The Bloke in the preceding years, [End Page 2] publishing a few poems about Bill in an earlier work (“The Sentimental Bloke”, Bulletin). The publicity paid off because by 1920 approximately 110,000 copies of the book had sold in Australasia and the United Kingdom (McLaren 92). That was an astonishing figure for any Australian work given the country’s population was less than five million at the time. Yet it hardly represented the total number of those familiar with its verse. Reports of The Bloke being read aloud in workplaces, performed on recital stages, borrowed from the New South Wales Bookstall Company Library and handed around among Australian servicemen indicate that it reached a considerably larger audience (Chisholm 58; Lyons and Taksa 67; Laugesen 51).

In 1919, the Australian film-maker Raymond Longford released a cinematic version of The Sentimental Bloke. Longford’s film was also a commercial success. It broke box-office records for an Australian-made film after it premiered in Melbourne that October (Bertrand; Pike and Cooper 120). A theatrical version of The Bloke was also successful after it opened at Melbourne’s King’s Theatre in September 1922. It starred Walter Cornock in the lead role, a man described for years afterwards as the “Original Sentimental Bloke” (“Walter Cornock Coming”; “Pot Luck”). The production played for twelve weeks in Melbourne before touring Australia and New Zealand for almost two years. Versions of the musical continued to be performed throughout Australasia for the rest of the decade, during which time recitations of the verse were also broadcast on radio and performed on the elocution stage (e.g. “Today’s Radio”; “Today’s Broadcasting”; “‘The Sentimental Bloke’: A Triumph of Elocution”).

Inspired by the success of The Sentimental Bloke, Dennis wrote four loosely-connected works of verse between 1916 and 1924. These were The Moods of Ginger Mick (1916), Doreen (1917), Digger Smith (1918) and Rose of Spadgers (1924). The Moods of Ginger Mick was also narrated by Bill and became a best-seller in its own right. It concerned the decision by Bill’s larrikin friend Ginger Mick to enlist in the Australian Imperial Forces and travel overseas to take part in the war. Ending with Mick’s tragic death in battle, it had sold over 70,000 copies by 1920 (McLaren 119). Ginger Mick was also made into a film by Raymond Longford in 1920 (Pike and Cooper 129). Although beyond the scope of my discussion here, fresh adaptations of The Bloke continued to appear throughout the rest of the century. These included a talkie film directed by Frank Thring in 1932 (poorly executed and unpopular, and thus omitted here), a ballet by Victoria’s Ballet Guild in 1952, a new stage musical and recordings of the verse by the country music singer Tex Morton in the 1960s, a television drama in 1976, and another rendition in dance by the Australian Ballet in 1985 (Boyd; Dermody; McLaren 199–200; Ingram). Across this period the book continued to sell: indeed, it is still the highest-selling work of poetry in Australian history (Butterss 2009: 16).

The larrikin everyman

When The Songs of a Sentimental Bloke first appeared, some critics hailed Bill as a novel figure in Australian popular culture. According to a writer for the Sydney Morning Herald, Dennis had broken new ground with the work: “a poetic cycle has never been written about such an unpoetic individual as Bill” (“The Sentimental Bloke” SMH 1915). [End Page 3] This claim was inaccurate. Dennis was not the first Australian writer to use a rough male figure as a romantic protagonist. Four years earlier, in fact, the Sydney-based writer Louis Stone had published Jonah, a novel about a street-fighting larrikinwho fell in love with a poor-but-genteel woman and struggled to win her regard. The Melbourne writer Edward Dyson had also included a romantic larrikin as a supplementary character in his collection of narratively-connected sketches, Fact’ry ’Ands (1906).

Back in the 1890s, the romantic larrikin had been sent up in the odd vaudeville act performed on Australia’s Tivoli Theatre circuit. These were modelled on English offerings about romantic Cockneys such as Albert Chevalier’s famous music-hall song, “My Old Dutch” (Bellanta Larrikins 35). The use of Cockney figures to voice masculine romantic sentimentality was indeed a feature of British popular culture from the last years of the nineteenth century. In Australia, however, theatrical songs such as “I’ve Chucked Up the Push for My Donah” (meaning “I’ve given up my street-fighting friends for my sweetheart”) had a mocking rather than celebratory air. Created in 1892 for the touring British burlesque comedian, E. J. Lonnen, this act ridiculed the very concept of larrikin romance (Bellanta Larrikins 36).

Though the idea of writing about a romantic larrikin was not original, the way in which Dennis went about it was. The bushman had long been presented sympathetically in Australian culture: a spare, usually solitary figure often portrayed as the essence of the Australian character. The same could not be said for the urban larrikin. In spite of Dyson’s and Stone’s efforts and the occasional story by Henry Lawson (e.g. “Elder Man’s Lane”), larrikins had overwhelmingly been portrayed as vulgar or frightening before Dennis published his work. Back in the 1880s, in fact, the press had fomented a full-scale moral panic about a “larrikin menace” in the colonial capitals after a number of nasty pack rapes of young women took place in inner-industrial Sydney. News reporters had written sensational stories of these outrages, calling their youthful perpetrators larrikin “brutes” and “fiends.” (Bellanta Larrikins 86–91). By the turn of the century, some writers and artists had started creating mocking caricatures of larrikins – the vaudeville routine just mentioned being an obvious example. Bill was obviously different from these earlier representations in that he was offered as a subject with whom audiences could identify.

The fact that Bill was offered to audiences as a subject of affectionate identification was apparent from the opening moments of The Sentimental Bloke. He was depicted in the throes of dissatisfaction with his ne’er-do-well life, wishing for something more uplifting, though he scarcely knew what it might be:

… As the poit sez, me ‘eart ’as got

The pip wiv yearning for … I dunno wot.

The preface, written by Henry Lawson, an iconic literary figure in Australian culture, signaled that this yearning of Bill’s gave him the status of everyman. “Take the first poem”, he wrote. “How many men… have had the same feeling – the longing for something better – to be something better?” Bill was thus presented as an ordinary “bloke” rather than the denizen of a brutish underworld. Though his quaint vernacular and lack of guile, he was able to voice the feelings of any fundamentally decent man, rough around the edges or otherwise. [End Page 4]

The romantic properties of The Sentimental Bloke

Bill might have appeared alone and vaguely yearning in the opening stanzas of The Sentimental Bloke, but it was clear from the next poem that the narrative concerned romantic love. From that moment, the plot proceeded almost as if anticipating Pamela Regis’ hard-line definition of romantic fiction in her Natural History of the Romance Novel. Following its trajectory, one can tick off each of her “eight essential elements” of romantic narratives (30). In the first place, it began with a description of “the initial state of society in which heroine and hero must court” in the form of Bill’s disconsolate musing about his larrikin life (30). It then proceeded to the meeting between hero and heroine; introduced obstacles to their union in spite of their mutual attraction; and came to a point of what Regis calls “ritual death” (35–6), in which it seemed impossible that Bill would prove himself capable of true romance. As one would expect, it then showed Bill’s prospects being reborn, ending with the pair joyfully united against the odds.

The first obstacle to Bill’s romantic union with Doreen was in the form of a straw-hatted suitor, a man Bill called the “stror ‘at coot” (47–52). Unable to help himself, he challenged this socially-superior rival to a fist-fight (50). Doreen was so displeased by this show of roughness that she quarreled and split from Bill. The pair reconciled soon afterwards, after Bill heard her singing a plaintive love-ballad at a neighborhood “beano” (party) and decided to make amends. A more serious obstacle arose after the pair was wed. This took place after Bill was tempted into a drunken bender with his larrikin mate, Ginger Mick. Nursing his hangover in bed the next day, he was painfully aware that he might have destroyed his romance with Doreen. “Eight weeks uv married bliss / Wiv my Doreen, an’ now it’s come to this!” (86). This point of “ritual death” was soon turned to new life, however, when the couple left the city for a small farm. In the final moments of the action, Bill and Doreen appeared blissfully ensconced in their own cottage, mutually delighting in a newborn son.

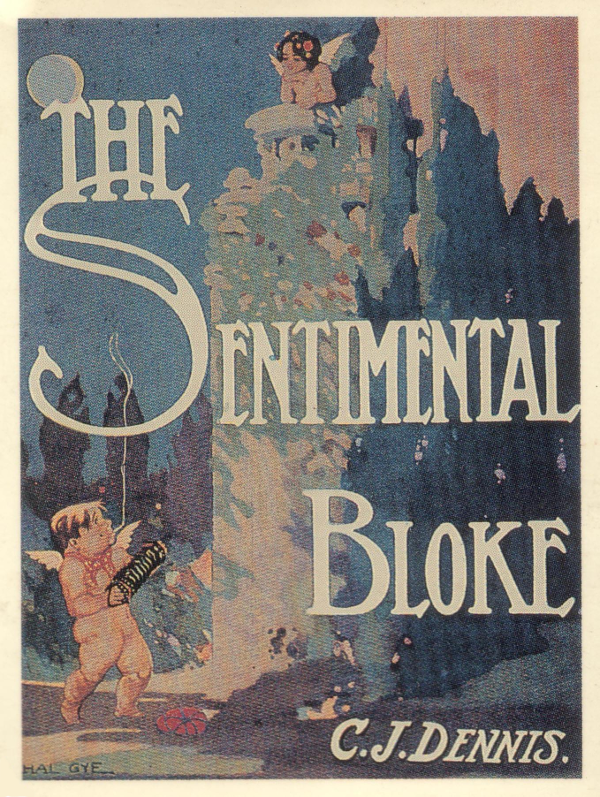

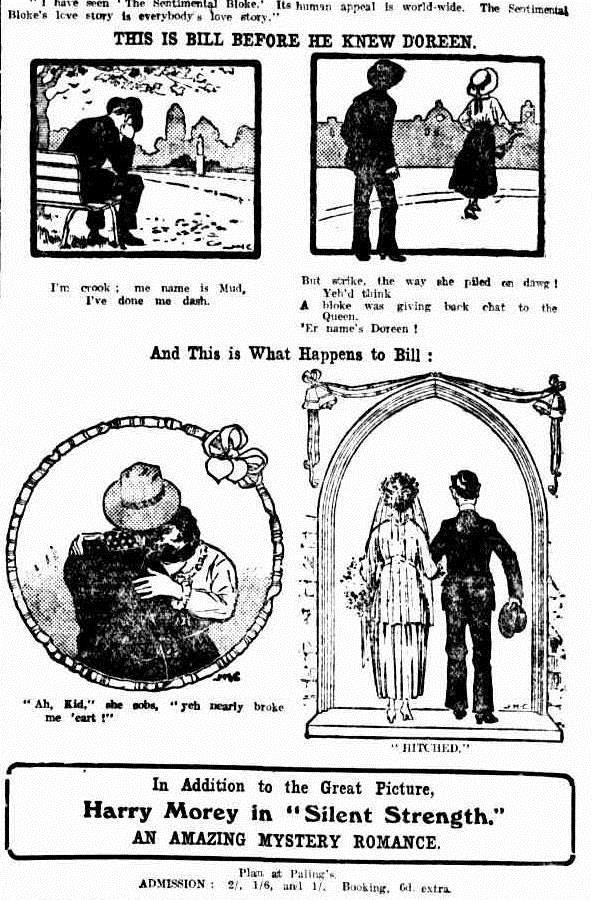

The illustrations accompanying the print version of The Sentimental Bloke highlighted its romantic properties. Drawn by Dennis’ friend Hal Gye, they portrayed Bill as a “Cupid” or “chivalric innocent” (Elliott 254; Cross 57), complete with chubby thighs and stubbily diaphanous wings. On a dust-jacket for an early edition, Gye depicted the couple à la Romeo and Juliet, with a cherub-like Bill playing a concertina at the foot of a balcony as Doreen looked down from above (Figure 1). Advertisements for the silent film similarly highlighted its romantic character. One created for West’s Olympia cinema franchise broke down the narrative into its key romantic elements. It comprised four cartoons representing stages in Bill and Doreen’s love-story. In the first, Bill appeared, sad and lonely before he met Doreen; in the second, Doreen was shown snubbing Bill after their quarrel; in the third, the pair were tearfully reconciled; and in the fourth, “hitched.” [End Page 5]

[End Page 6]

[End Page 7]

Australian masculinity and the “open secret” of romantic sentimentality

Since The Sentimental Bloke was so obviously presented as a romance, one might be forgiven for expecting that the text and its protagonist would have been ridiculed in the Australia of its day. A great deal of what we hear about Australian culture and masculinity in this period emphasizes the dry-witted bushmen as a key figure, “laconic” and “sentimental as a steam-roller” (“Anzac Types” cited in Caesar 150). Much has also been written about the celebration of the tough and irreverently humorous returned serviceman in 1920s Australia (e.g. Seal; Caesar; Williams 127–33; Fotheringham 2010). Historian Richard Waterhouse has argued that opposition to Victorian-era piety and morality was paramount in urban Australia’s popular culture by the end of the First World War (176), while Peter Kirkpatrick (52) and Tony Moore (117–43) show that members of interwar Sydney’s bohemian scene regarded marriage and domesticity contemptuously. In actual fact, one of these bohemians did ridicule the Bloke for his romantic sentimentality. The earlier-mentioned artist and writer, Norman Lindsay, burnt a copy of The Sentimental Bloke on a crucifix and described Ginger Mick as “maudlin rubbish” (Butterss 2009: 16; 2005: 118).

Fascinatingly, though, mocking reactions of this kind were rare. Even masculinist papers such as the Bulletin and the Lone Hand produced glowing reviews (“The Sentimental Bloke” Bulletin; “The Songs of a Sentimental Bloke”; “C. J. Dennis”). The vast majority of critics responded to Bill much as he was presented to them: with affection and/or empathy. After the silent film was released, for example, a reviewer for the Green Room suggested that he had been nervous about whether Arthur Tauchert, the actor playing Bill, would do the justice to the character. “Nearly everybody knew Dennis’ creation by heart, and we all had a hazy mental vision of the gentleman who loved Doreen to distraction”, he wrote. Happily, the actor had acquitted himself admirably: “Tauchert’s Bloke is the Bloke of Blokes” (“C. J. Dennis’ Characters”). Five years later, in 1924, a country Victorian critic waxed rapturous about The Sentimental Bloke musical: “You’ll laugh, you’ll cry… and you’ll join in and say it is the greatest of all” (“The Sentimental Bloke” Horsham Times).

Reports of audiences laughing and noisily applauding recitations of The Bloke point to the fact that ordinary citizens also responded warmly to Bill (e.g. “Lawrence Campbell’; “The Sentimental Bloke” SMH 1922). One of Dennis’ friends, Alec Chisholm, would later recall the enthusiasm he and his colleagues at a country newspaper felt for The Bloke early in its career. Even the most “hard-bitten” of compositors used to beg him to read from it as they worked, Chisholm wrote. “We knew in particular ‘The Introduction’, that delicate tale … of the initial meeting between the Bloke and the ‘bonzer peach’ [Doreen]” (58). Another middle-class reader recalled that even though she had not been a fan of the colloquial verse during her childhood in the 1920s, “The Sentimental Bloke was a great favorite of Dad’s” (cited in Lyons and Taksa 67).

Because The Sentimental Bloke relied so heavily on colloquialisms, it was never regarded as Literature. As Martyn Lyons and Lucy Taksa observe, the work never received “official sanction” (67). It was left off school and university curricula and ignored by most academics until the late twentieth century. Yet this lack of official approval offers vital clues as to why Bill was regarded so affectionately. One of the reasons he was so widely favored [End Page 8] was that he tapped a vein of “unofficial” knowledge about men and romance that had long existed on the sly, as it were, in Australian culture. The Bloke presented masculine tenderness as what Eve Sedgwick would call an “open secret” (145), in other words. Its comedy sprang from the suggestion that all men had the capacity for romantic feeling, even though they tried to hide it beneath a hard-bitten or laconic exterior. Everyone knew that men could be sentimental even though “officially” this was not supposed to be true.

One of the ways that The Bloke gestured at an ordinary belief in male sentimentality was via its original title, The Songs of a Sentimental Bloke. By this means it likened its fourteen poems to romantic songs performed by the earnest young Bill. Male vocalists sang romantic ballads such as “Annie Laurie” and “Belle Mahone” any night of the week in Australian homes or vaudeville shows in the years before, during and immediately after the war (Bellanta “Australian Masculinities”). Just in case fans missed the allusion, the sequel Ginger Mick made explicit reference to these commonplace songs. In a letter written to Bill from a military camp in Egypt, Ginger Mick declared that ballads such as “Bonnie Mary” and “My Little Grey Home in the West” were dear to Australian servicemen’s hearts. Laced with memories of sweethearts and romantic picnics, these songs helped to sustain Australia’s soldiers as they coped with battle far from home. “When I’m sittin’ in me dug-out wiv me rifle on me knees”, Mick began:

An’ a yowlin’, ‘owlin’ chorus comes a-floatin’ up the breeze,

Jist a bit o’ “Bonnie Mary” or “Long Way to Tipperary”–

Then I know I’m in Australia, took an’ planted overseas.

… O, it’s “On the Mississippi” or “Me Grey ‘Ome in the West”.

If it’s death an’ ’ell nex’ minute they must git it orf their chest.

’Ere’s a snatch o’ “When yer Roamin” – “When yer Roamin’ in the Gloamin”.

’Struth! The first time that I ’eard it, wiv me ’ead on Rosie’s breast.

We wus comin’ frum a picnic in a Ferntree Gully train…

But the shrapnel made the music when I ’eard it sung again (61).

In her rich study of Australian servicemen’s reading habits and entertainments during the war, Amanda Laugesen reveals a considerable interest in romantic and otherwise sentimental cultural forms. In their letters home, she tells us, numerous Australian soldiers mentioned the works of Gene Stratton Porter, “a [female] American novelist who wrote romantic novels with a strong moral message and whose works sold in the millions” (62). Others mentioned the sentimental novelists Marie Corelli, Jean Webster, Hall Caine and Charles Garvice (who also wrote under the female pseudonym Caroline Hart) (61–2) – many of whose works were made into films in the 1910s. Laugesen also notes that troop publications “clearly articulated a strong sentimentality focused on home and family” (61), and that servicemen’s vaudeville shows routinely featured romantic songs of the sort referred to in Ginger Mick (79–104; Bellanta “Australian Masculinities).

In pointing to a significant cross-gender interest in romantic ballads and novels, Laugesen gives us a sense of why Dennis was able to appeal to folk knowledge about masculine sentimentality in The Sentimental Bloke. Her examples also suggest that we need to revisit the standard scholarly accounts of male cultural preferences in early-twentieth century Australia. Those accounts tell us plenty about adventure novels and sporting [End Page 9] dramas (e.g. Crotty; Dixon; Fotheringham 1992). Some also tell us about “galloping rhymes” and stories about stoic bushmen (e.g. Schaffer; Murri; Dwyer), but are silent on the topic of a male investment in popular romance. As The Bloke’s success makes clear, however, neither representations of galloping adventurers nor of laconic bushmen amounted to the sum total of popular understandings about Australian masculinity. Nor did men confine themselves to cultural forms that promoted such stereotypical versions of masculinity in the early 1900s. Their cultural consumption was always more complex than that.

A plain approach to romance

If The Sentimental Bloke tapped a vein of unofficial knowledge about masculine romantic feeling, it also, as I said earlier, touched a cultural nerve. The work’s combination of comedy and sentiment sprang from the fact that masculine romance was indeed edgy territory in the war- and early interwar years. It is true that ballads such as “Bonnie Mary” continued to be performed and cherished in the 1920s and even beyond. They were starting to be seen as old-fashioned by then, however, with their quaveringly tender choruses and address of the beloved as “thou” and “thy” (“I have watched thy heart, dear Mary… / Bonnie Mary of Argyle”). Earnest songs of this kind were made the subject of irreverent parodies, in some cases by men who were embarrassed by their emotional impact and wanted to demonstrate that they were not in their thrall (Seal 57–9; Bellanta “Australian Masculinities” 426–7). Similar things may be said of the sentimentality focused on home and family among Australian servicemen during the war. That sentimentality had to be carefully managed in order to prevent it from detracting from military solidarity, hedged about by jokes and the celebration of male-on-male company (Seal 66, 75–7).

Contending claims made about the relationship between men and romantic sentiment became even more apparent after the armistice, when servicemen were being repatriated en masse into the world of civilian work and family. During this period, the allure of marriage and domesticity on the one hand, and of carousing and military fellowship on the other, made for a degree of ambivalence about both sets of ideals (Garton). It was in this context that The Sentimental Bloke’s suggestion that all men were romantic in spite of their hard exteriors (and friendship with mates) really came to the fore. Yet the work went a lot further than gesturing at the “open secret” of men’s romantic feelings. It also suggested that there was a distinctively masculine approach to romantic sentimentality that any man might adopt without fear of embarrassment, the hallmarks of which were plainness and straightforwardness. These were the qualities that marked out a “real” man’s romantic tendencies from a woman’s, and distinguished him from effeminate types.

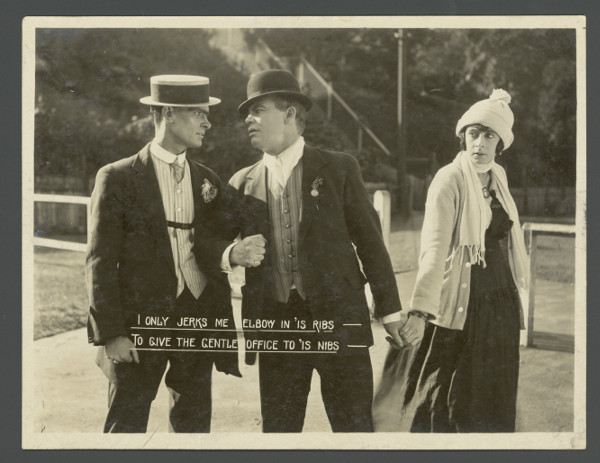

The key way in which The Sentimental Bloke constructed a masculine approach to romance was by juxtaposing the exemplary Bill with two other male characters, both of whom were portrayed as comparatively effete. The first of these men was the parson who conducted Bill’s marriage to Doreen. The second was the straw-hatted rival who also sought Doreen’s hand. Of these, the parson was the most effeminate. In both Dennis’ original text and Longford’s adaptation, he was dressed in flowing vestments and comically labelled “’is nibs” or “the pilot cove” by Bill. At the start of the wedding scene, Bill mocked [End Page 10] his mincing manner, mimicking his reading of the vows in what was supposed to be a sing-song voice: “An’–wilt–yeh–take–this–woman–fer–to–be / Yer–wedded–wife?” Bill then interjected robustly:

O, strike me! Will I wot?

Take ’er? Doreen? ’E stan’s there arstin’ me!

As if ’e thort per’aps I’d rather not!

Take ’er? ‘E seemed to think ’er kind was got

Like cigarette-cards, fer the arstin’.

Still, I does me stunt in this ’ere hitchin’ rot,

An’ speaks me piece: “Righto!” I sez, “I will.” (77)

As the ceremony proceeded, Bill became steadily more frustrated with its “swell” and “stylish” character:

… Ar, strike! No more swell marridges fer me!

It seems a blinded year afore ’e’s done.

We could ’a’ fixed it in the registree

Twice over ’fore this cove ’ad ’arf begun.

I s’pose the wimmin git some sorter fun

Wiv all this guyver, an ’is nibs’s shirt.

But, seems to me, it takes the bloomin’ bun,

This stylish splicin’ uv a bloke an’ skirt. (79)

This scene was instrumental to The Bloke’s message that plainness and directness were characteristic of a masculine approach to romance. There was no doubting that Bill was powerfully in love with Doreen (“Take ’er? … ’E stan’s there arstin’ me! / As if ’e thort per’aps I’d rather not!”) Unlike the parson or the “wimmin”, however, he believed that his feelings stood for themselves without need for elaborate packaging.

The idea that Bill’s stance on romance was solidly masculine was reinforced by his contrast with the “stor ’at coot.” This “coot” was full of simpering smiles and “tork” about his office job in Doreen’s company. Bill, on the other hand, was incapable of glib eloquence: “No, I ain’t jealous – but – Ar, I dunno!” (39). His inability to “tork the tork” was portrayed as a sign of the genuineness of his romantic intentions: a cause for laughter, perhaps, but also proof of his salt-of-the-earth straightforwardness. The “coot” also dressed in what Bill contemptuously described as a “giddy tie an’ Yankee soot” (49), while Bill himself preferred ordinary street attire. The film made this distinction even more conspicuous by choosing the weedy Harry Young to play the “coot”. His slender physique was an obvious foil to the burliness of Arthur Tauchert’s Bill. [End Page 11]

Australian masculinity and the Americanized culture of romantic love

Preserved in the subtitles to the film, Dennis’ description of the coot’s dress as “Yankee” added another dimension to the representation of Bill’s masculinity in The Sentimental Bloke. In the eyes of certain interwar critics, at any rate, the Bloke was seen as quintessentially Australian, a refreshing change from the American characters who were becoming increasingly prominent in Australian popular culture. As early as 1916, in fact, a writer for the Sydney Morning Herald described The Bloke’s use of an Australian vernacular as a welcome break from the “Yankee slang” so often served up to Australian audiences in “comedies and in plays dealing with the American criminal class” (“The Sentimental Bloke” SMH 1916). Comments of this kind were also made in relation to Longford’s film. One Brisbane critic praised its Australian scenery and ambience, pleased that it moved “right away from the rather hard and artificial American convention” (“Entertainments.”)

The idea that Bill represented a specifically Australian masculinity was partly influenced by the surge of interest in national identity that accompanied Australia’s effort in the First World War (Seal; Williams). Yet it was also influenced by a consciousness of the [End Page 12] growing clout of American popular culture in Australian society. As Jill Matthews tells us, all manner of mass-produced American commodities began making their way to Australia during the 1910s. These included “technology, machines and gadgets, business methods, fashions and amusements” (Matthews 11). The arrival of “Yankee” commodities was even more apparent in the 1920s, a decade in which American manufacturers and entertainment companies vigorously expanded their international reach (12; Teo 2006: 182; Glancy). The majority of the Australian public was manifestly enthusiastic about American culture and products in this period; there would not have been a market for them otherwise. Even so, a niggling concern about Americanization was growing among the general populace. This was apparent in a defensive insistence on the Australianness of The Bloke, which in cinematic form was vaunted as a “True Australian Film.” After the premiere of Longford’s Bloke, a writer for Sydney’s Picture Show even commended him for marshaling a team “as great in their particular sphere of acting as any teams D. W. Griffith ever assembled”, attempting to place him on a par with the great American filmmaker (cited in Tulloch 65).

In press interviews about his films in the early interwar period, Longford emphasized his nationalist passion for Australian settings and characters (“C. J. Dennis’ Characters”; “The Man Behind ‘Rudd’s New Selection’” 32). Later in the 1920s he would speak bitterly of the early troubles he had experienced trying to convince cinemas to screen The Sentimental Bloke. Australian film distributors and cinema owners had been so much under the thumb of American operators that he had been forced to hold the premiere for the film in Melbourne Town Hall, he complained (Blake 35–36). These complaints reinforced the fact that the Bloke came to be regarded as “intensely Australian in type” during the 1920s, investing him with a normative power through his association with Australian national identity (“Sentimental Bloke” Townsville Daily Bulletin; see also “The Sentimental Bloke” Brisbane Courier). More pertinently, they helped to ensure that Bill’s approach to romance was understood as an Australian alternative to the American culture of romantic love.

As Hsu-Ming Teo tells us, Australia’s culture of romantic love was undergoing a process of Americanization in the 1920s (2006). By this, she means that a more commodified approach to courtship and romantic fantasy was emerging, modeled on developments that had already taken place in the United States. For decades in America, a premium had been placed on gifts and paid outings as the key means for a man to express romantic feelings towards a woman (174–77; Illouz). American popular culture also celebrated men who made declarations of love with a suave eloquence: Al Jolson singing the smash hit “You Made Me Love You” (1913), or the alluring heroes of romantic films such as The Sheik (1919) and The Big Parade (1925). In addition, American advertisers promoted commodities such as soap and lipstick to female consumers on the basis that they would enhance their chances of romance with glamorous men. A similar process was just starting to become evident in Australia at the end of the First World War.

The Americanizing influences on Australia’s culture of romantic love were largely directed at young women in the 1920s. Advertisers did not begin inducting Australian men into romanticized consumerism until the 1950s. Before then, “items of personal or leisure consumption for men” – products such as Berger Paints, Dunlop rubber, Boomerang whisky, and General Motors-Holden cars – were advertised through images of factories rather than appeals to men as consumers with romantic desires (Teo 2006: 181–86). This [End Page 13] made for a disconnect between young Australian men’s and women’s approach to the culture of romantic love that became increasingly apparent over the interwar era. The disparity was strikingly evident by the time American servicemen arrived in Australia in their thousands during the Second World War. Young Australian women tended to regard these “Yanks” as romantic heroes, while Australian men resented the Americans’ success with “their” women and superior access to consumer goods (Lake 1990; 1992; Connors et al 140–88).

Knowing what we do about the representation of Bill in The Sentimental Bloke helps us understand why Australian men’s approach to romantic love tended to be so different from Australian women’s. The work treated Bill’s lack of glamor and suavity as a boon; proof not just of the genuineness of his romantic intentions but his Australianness. Crucially, it also suggested that Australian men risked compromising their masculinity if they entered too enthusiastically into the Americanized culture of romantic consumerism. “Intensely Australian” types were neither supposed to indulge in glibly romantic “tork” nor trouble over their appearance if they wanted to avoid accusations of effeminacy. They were supposed to regard being plain and unadorned as a good thing, even in their dealings with women. This was not because Australian men did not care about romance, however, but rather because such things detracted from the honest force of their feelings.

The gender of romantic love

With all this talk of Australianness, it would be easy to assume that non-Australian scholars have little to learn from The Sentimental Bloke. This is not the case. Admittedly, the fact that plainness and straightforwardness were claimed to be characteristic of “intensely Australian types” suggests that an unusual degree of emphasis on these qualities could be found “Down Under.” Yet Australia was not the only place in which one could find critiques of elaborately packaged sentimentality, or of an Americanized culture of romantic love, in the war- and interwar years. In Hollywood and the Americanization of Britain, for example, Mark Glancy discusses divisively gendered reactions to the romantic actor Rudolph Valentino, whose glamorous masculinity was regarded as suspicious by many British men in the 1920s. In The Decline of Sentiment, American film scholar Lea Jacobs also speaks of a decisive shift in cultural taste taking place in the United States if not also Anglophone society more broadly, beginning in the 1910s and reaching critical mass the following decade. This shift was away from the “genteel” conventions of Victorian sentimental culture, she tells us, and towards a more informal and understated aesthetics. Its predominantly male advocates presented it in gendered terms: as a movement away from feminine standards of taste towards something simultaneously more modern and robustly masculine (1–24).

As Jacobs sees it, the movement away from elaborate or genteel sentimentality attracted a motley collection of participants. Some were modernist cultural producers. Others included the naturalist writers, film-makers and critics who gravitated to New York in the 1910s. Both the naturalist novelist Theodor Dreiser and the critic H. L. Mencken, for example, were keenly interested in experimenting with vernacular speech. They believed [End Page 14] that the vernacular conveyed feeling more honestly and forcefully than the polished language of Literature (11–12). In this they had something in common with Dennis, regardless of their other differences. Similarly, the film-maker Thomas de Grasse and his colleagues had something in common with Raymond Longford in spite of the fact that they were unlikely to have been aware of each other’s work. Like Longford, America’s naturalist film-makers rejected glamorous characters in favor of depicting “plain folks” on screen in the 1910s and 1920s (29).

While there was a wide-ranging reaction against Victorian-era sentimentality in English-speaking society, The Sentimental Bloke suggests that scholars such as Jacobs go too far. It reminds us that not all reactions against “genteel” involved a rejection of sentimentality per se. An analogous point may be made about reactions against a glamorously consumerist culture of romantic love. It was possible for a critic to take umbrage at the commodification of romantic love in American[ized] popular culture without spurning romantic love in its entirety. Jacobs’ use of the phrase “decline in sentiment” is misleading because of this, for it implies a wholesale rejection of tender feeling rather than a more limited movement away from a certain sentimental style among certain cultural arbiters.

Another reason that the concept of a “decline in sentiment” is misleading is that it overlooks the fact that “genteel” sentimental forms continued to be consumed and enjoyed in Anglophone culture on the sly, in spite of the fact that they were criticized as old-fashioned or embarrassing. A continued interest in romantic ballads was an obvious example of this. In Britain, at any rate, regular performances of such ballads by male vocalists continued well after the Second World War (Hoggart 53–66). More pertinently, the concept of a wholesale feminization of sentiment – of the rejection of sentiment on the basis of its connections to femininity – overlooks the likelihood that a range of “masculine” expressions of romantic sentimentality developed in the early twentieth century. I have explored only one example of this here, although I began by noting that Australia’s first examples of romantic larrikins were influenced by British depictions of romantic Cockney men. It would be fascinating to explore the use of the Cockney vernacular and characters to voice masculine approaches to romantic love in British culture in the early 1900s, as well as to investigate analogous examples in the United States and elsewhere. The multi-media character and enormous popularity of The Sentimental Bloke in Australia certainly suggests that examples of masculine romance might fruitfully identified and explored elsewhere in Anglophone society.

The persistence of masculine sentimentality in Anglo- or American culture across the twentieth century has attracted attention from a number of scholars in recent years. International scholars such as Jennifer Williamson and Eve Sedgwick (131–46) have indeed grappled with similar issues to those discussed in an Australian context here (see also Chapman and Hendler; Shamir and Travis.) Sedgwick in particular has highlighted the fact that heterosexual men’s expressions of tender feeling remained an “open secret” in American culture and everyday life long after masculinity was “officially” supposed to have become incompatible with sentimentality. At the very least, this work should alert romance scholars to the need to take the relationship between heterosexual masculinity and romantic sentimentality seriously. It suggests that romance scholars should give more [End Page 15] thought to the complex relationship between masculinity and romance in twentieth-century culture instead of treating romantic love as “feminized love”. Many men were uncomfortable with elaborate expressions of romantic feeling or the consumerist culture associated with American popular romance by the 1920s. Demeaning romance as feminine was not the only response to this discomfort, however – another was the construction of avowedly masculine articulations of romantic sentiment such as that of The Sentimental Bloke. [End Page 16]

Works Cited

Bellanta, Melissa. Larrikins: A History. St Lucia, Queensland: University of Queensland Press, 2012. Print.

—. “Australian Masculinities and Popular Song: The Songs of Sentimental Blokes, 1900–1930s.” Australian Historical Studies 43.3 (2012): 412–28. Print.

Bertrand, Ina. “The Sentimental Bloke: Narrative and Social Consensus.” Screening the Past: Aspects of Early Australian Film. Ed. Kerry Berryman. Canberra: National Film and Sound Archive, 1995. Print.

Blake, Les. “The Sentimental Bloke on Screen – A Stoush With the Yanks.” Victorian Historical Journal 64.3 (1993): 28–45. Print.

Boyd, David. “The Public and Private Lives of a Sentimental Bloke.” Cinema Journal 37.4 (1998): 3–18. Print.

Butterss, Phillip. “‘Compounded of Incompatibles’: The Songs of a Sentimental Bloke and The Moods of Ginger Mick.” Serious Frolic: Essays on Australian Humor. Ed. Fran de Groen and Peter Kirkpatrick. St Lucia, Queensland: University of Queensland Press, 2009. 16–30. Print.

—. “‘Ar, If Only a Bloke Wus Understood!’ C. J. Dennis and The Songs of a Sentimental Bloke.” Living History: Essays on History as Biography. Ed. Susan Magarey and Kerrie Round. Adelaide: Australian Humanities Press, 2005. 113–26. Print.

“C. J. Dennis: ‘The Sentimental Bloke’ and ‘Digger Smith.’” Lone Hand (Sydney). 2 December 1918: 572–3. Print.

“C.J. Dennis’ Characters Step From His Favorite Book and Live.” Green Room (Sydney). 1 November 1919: 10. Print.

Caesar, Adrian. “National Myths of Manhood: Anzacs and Others.” The Oxford Literary History of Australia. Ed. Bruce Bennett and Jennifer Strauss. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998: 147–68. Print.

Chapman, Mary and Glenn Hendler, eds. Sentimental Men: Masculinity and the Politics of Affect in American Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999. Print.

Chisholm, Alec. H. The Making of a Sentimental Bloke: A Sketch of the Remarkable Career of C. J. Dennis. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 1963. Print.

Clark, Suzanne. Sentimental Modernism: Women Writers and the Revolution of the Word. Indiana University Press: Bloomington and Indianapolis, 1991. Print.

Connors, Libby, Lynette Finch, Kay Saunders and Helen Taylor. Australia’s Frontline: Remembering the 1939–45 War. St Lucia, Queensland: University of Queensland Press, 1992. Print.

Cross, Gary. The Cute and the Cool: Wondrous Innocence and Modern American Children’s Culture. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004. Print.

Crotty, Martin. Making the Australian Male: Middle-Class Masculinity 1870–1920. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 2001. Print.

Dennis, C. J. The Songs of a Sentimental Bloke. Sydney: Angus and Robertson, 1915. Print.

—. The Moods of Ginger Mick. Sydney: Angus and Robertson, 1916. Print.

—. Doreen. Sydney: Angus and Robertson, 1917. Print.

—. Digger Smith. Sydney: Angus and Robertson, 1918. Print.

—. Rose of Spadgers. Sydney: Angus and Robertson, 1924. Print. [End Page 17]

Dermody, Susan. “Two Remakes: Ideologies of Film Production 1919–1932.” Nellie Melba and Ginger Meggs: Essays in Australian Cultural History. Ed. Susan Dermody, John Docker and Drusilla Modjeska. Malmsbury, Victoria: Kibble Books, 1982: 33–59. Print.

Dixon, Robert. Writing the Colonial Adventure: Race, Gender and Nation in Anglo-Australian Popular Fiction, 1875–1914. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995. Print.

Dwyer, Brian. “Place and Masculinity in the Anzac Legend.” Journal for the Association of the Study of Australian Literature (1997): 226–31. http://www.nla.gov.au/openpublish/index.php/jasal/article/viewFile/2833/3247. Web.

Dyson, Edward. Fact’ry ‘Ands. Melbourne: G. Robertson, 1906. Print.

Elliott, Brian. “C. J. Dennis and The Sentimental Bloke.” Southerly. 3 September 1977: 243–65. Print.

“Entertainments.” Brisbane Courier. 26 December 1919: 7. Web.

Felski, Rita.“Kitsch, Romantic Fiction and Male Paranoia: Stephen King Meets the Frankfurt School.” Continuum. 4.1 (1990):

http://wwwmcc.murdoch.edu.au/ReadingRoom/4.1/Felski.html. Web.

Forsyth, Hannah. “Sex, Seduction, and Sirens in Love: Norman Lindsay’s Women.” Antipodes. 19.1 (2005): 58-66. Print.

Fotheringham, Richard. “Laughing It Off: Australian Stage Comedy After World War I.” History Australia. 7.1 (2010): http://journals.publishing.monash.edu/ojs/index.php/ha/article/view/ha100003/125. Web.

—. Sport and Australian Drama. Cambridge and Melbourne: Cambridge University Press, 1992. Print.

Garton, Stephen. “War and Masculinity in Twentieth-Century Australia.” Journal of Australian Studies 22.56 (1998): 86–95. Print.

Giddens, Anthony. The Transformation of Intimacy: Sexuality, Love and Eroticism in Modern Societies. Cambridge: Polity Press, 1992. Print.

Glancy, Mark. Hollywood and the Americanization of Britiain: From the 1920s to the Present. London: I. B. Tauris, 2014. Print.

Hoggart, Richard. The Uses of Literacy: Aspects of Working-Class Life with Special Reference to Publications and Entertainment. Middlesex: Penguin, 1963. Print.

Huyssen, Andreas. After the Great Divide: Modernism, Mass Culture, Postmodernism. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1986. Print.

Illouz, Eva. Consuming the Romantic Utopia: Love and the Cultural Contradictions of Capitalism. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997. Print.

Ingram, Geoffrey. “Dancing the Bloke.” Brolga 4 (1996): 33–36. Print.

Jacobs, Lea. The Decline of Sentiment: American Film in the 1920s. University of California Press: Berkeley, 2008. Print.

Kirkpatrick, Peter. The Sea Coast of Bohemia: Literary Life in Sydney’s Roaring Twenties. St. Lucia, Queensland: University of Queensland Press, 1992. Print.

Lake, Marilyn. “The Desire for a Yank: Sexual Relations Between Australian Women and American Servicemen During World War II”. Journal of the History of Sexuality 2.4 (1992): 621–633. Print.

—. “Female Desires: The Meaning of World War II”. Australian Historical Studies. 24.95 (1990): 267–284. Print. [End Page 18]

Laugesen, Amanda. Boredom Is the Enemy: The Intellectual and Imaginative Lives of Australian Soldiers in the Great War and Beyond. Burlington, U.K.: Ashgate, 2012. Print.

“Lawrence Campbell: ‘The Sentimental Bloke’”. Wellington Times (NSW). 9 September 1920: 4. Web.

Lawson, Henry. “Elder Man’s Lane: XII: A Reconnoitre With Benno”. Bulletin (Sydney). 15 July 1915: 22.

—. Preface to C. J. Dennis, The Songs of a Sentimental Bloke. Sydney: Angus and Robertson, 1915. Print.

Lyons, Martyn and Lucy Taksa. Australian Readers Remember: An Oral History of Reading 1890–1930. Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 1992. Print.

McLaren, Ian. C. J. Dennis: A Comprehensive Bibliography Based on the Collection of the Compiler. Adelaide: Libraries Board of South Australia, 1979. Print.

McNaughton, J. “Belle Mahone”. Songsheet in the Lester S. Levy Sheet Music Collection, Sheridan Libraries, Johns Hopkins University, Box 129, Item 13.

Matthews, Jill Julius. Dance Hall and Picture Palace: Sydney’s Romance With Modernity. Sydney: Currency Press, 2005.

Moore, Tony. Dancing With Empty Pockets: Australia’s Bohemians. Sydney: Pier 9. 2012. Print.

Murri, Linzi. “The Australian Legend: Writing Australian Masculinity/Writing ‘Australian’ Masculine”. Journal of Australian Studies 22:56 (1998): 68–77. Web.

Pike, Andrew and Ross Cooper. Australian Film 1900–1977. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1981. Print.

“Pot Luck.” Examiner (Launceston, Tasmania). 16 June 1931: 8. Web.

Regis, Pamela. A Natural History of the Romance Novel. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2003. Print.

Schaffer, Kay. Women and the Bush: Forces of Desire in the Australian Cultural Tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988. Print.

Seal, Graham. Inventing ANZAC: The Digger and National Mythology. St Lucia, Queensland: University of Queensland Press, 2004. Print.

Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky. The Epistemology of the Closet. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990. Print.

“‘Sentimental Bloke’ and ‘On Our Selection’.” Townsville Daily Bulletin (Queensland). 7 June 1923: 3.

Shamir, Milette and Jennifer Travis, eds. Boys Don’t Cry? Rethinking Narratives of Masculinity and Emotion in the U.S. New York: Columbia University Press, 2002. Print.

Shugart, Helene A. and Catherine Egley Waggoner. Making Camp: Rhetorics of Transgression in U.S. Popular Culture. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: University of Alabama Press, 2008. Print.

Stone, Louis. Jonah. London: Methuen, 1911. Print.

Teo, Hsu-Ming. Desert Passions: Orientalism and Romance Novels. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2012.

—. “The Americanization of Romantic Love in Australia.” Connected Worlds: History in Transnational Perspective. Ed. Ann Curthoys and Marilyn Lake. Canberra: ANU E-Press, 2006. Print and web. [End Page 19]

“The Man Behind ‘Rudd’s New Selection’”. Picture Show (Sydney): 32–33. Web.

The Sentimental Bloke. Dir. Raymond Longford. Southern Cross Feature Film Company. 1919. Film.

“The Sentimental Bloke.” Brisbane Courier. 11 May 1923: 9. Web.

“The Sentimental Bloke”. Bulletin (Sydney). 14 October 1915: “The Red Page”. Print.

“The Sentimental Bloke.” Horsham Times (Victoria). 5 September 1924: 6. Web.

“The Sentimental Bloke.” Sydney Morning Herald. 16 November 1915: 8. Web.

“The Sentimental Bloke.” Sydney Morning Herald. 11 September 1916: 4. Web.

“The Sentimental Bloke.” Sydney Morning Herald. 4 July 1922: 10. Web.

“The Sentimental Bloke: A Triumph of Elocution”. Mail (Adelaide). 23 September 1922: 3. Web.

“‘The Sentimental Bloke’: Successful Private Screening of Film Version.” Advertiser (Adelaide, South Australia). 27 November 1918: 11. Web.

“The Sentimental Bloke: The Play Not the Picture.” Advocate (Burnie: Tasmania). 24 November 1923: 4. Web.

“The Songs of a Sentimental Bloke”. Lone Hand (Sydney). December 1915: 64.

“Today’s Broadcasting”. Register (Adelaide). 22 October 1926: 10. Web.

“Today’s Radio”. Townsville Daily Bulletin (Qld). 20 June 1927: 11. Web.

“True Australian Film: ‘The Sentimental Bloke’.” Register (Adelaide, South Australia). 4 December 1919: 8. Web.

Tulloch, John. Legends on the Screen: The Australian Narrative Cinema, 1919–1929. Sydney: Currency Press, 1981. Print.

“Walter Cornock Coming: Original Sentimental Bloke.” Mirror (Perth). 18 February 1928: 6. Web.

Waterhouse, Richard. Private Pleasures, Public Leisure: A History of Australian Popular Culture Since 1788. Melbourne: Longman, 1995. Print.

Williams, John F. The Quarantined Culture: Australian Reactions to Modernism 1913–1939. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995. Print.

Williamson, Jennifer A. “Introduction: American Sentimentalism From the Nineteenth Century to the Present’”. The Sentimental Mode: Essays in Literature, Film and Television, ed. Jennifer A. Williamson, Jennifer Larson and Ashley Reed. Jefferson NC: McFarland & Co., 2014. Print. [End Page 20]