Sexting, or the creation and sharing of sexual messages, images, or videos via mediated communication (Burén and Lunde; Hasinoff), has become a normative practice (Madigan et al.). Some prior literature situates sexting as a form of deviant behavior (e.g., Lee et al.; Van Ouytsel et al.). However, people are motivated to sext for many reasons that do not include acts of defiance; rather, sexting is sometimes described as a normal relational activity with inherent benefits, as a way to explore sexuality, as a way to express intimacy and sexual interest, and as a form of sexual agency, self-disclosure, and relational maintenance (Angelides; Jenkins and Stamp; Speno and Aubrey; Van Ouytsel et al.). These positive sexting outcomes indicate that deviance does not fully explain the phenomenon of sexting.

Communication privacy management (CPM; Petronio) deals with how individuals share and manage private information and is applied to various social media contexts such as blogging, Facebook use, and online dating (Chennamaneni and Taneja; Child et al.; Waters and Ackerman). Specifically, Child and Petronio explicitly argued for the application of CPM within the study of digital technologies. New media offer a new way for individuals to manage their privacy concerns using the affordances present in the modality they use to sext. The current study seeks to extend the use of CPM of digital contexts to argue that individuals can meet some of their relational and personal needs by sharing sexually explicit messages. This creates a common understanding of trust with the recipient of the message, which in turn creates a shared privacy boundary.

From a CPM perspective, sexting represents a form of sharing private information. Individuals, therefore, assume personal ownership over their messages, have the right to control whom the messages are shared with, and create privacy rules and negotiate with one another to control who has access to their private information. Therefore, CPM provides a framework for understanding how social media affordances help individuals manage privacy boundaries when sexting and how boundary management can improve sexting experiences by reducing risk. Sexting creates a shared privacy bond, increased trust, privacy, and commitment within the relationship. Therefore, CPM can contribute to positive sexting experiences. Further, certain social media affordances offer utility in many social practices (Bazarova and Choi), and affordances such as modality permanence serve as a way to manage shared privacy boundaries. These factors can contribute to the relationship’s long-term well-being and longevity.

Consequently, this study provides another understanding for sexting that uses a CPM (Petronio) perspective to expand our understanding of sexting motives by examining the potential positive factors that influence individuals’ motivations for sexting including how risk, privacy, and trust influence their sexting experiences. Using CPM to study sexting offers an extension of the existing understanding of CPM and builds on existing research on CPM in mediated contexts.

Motivations for Sexting from a CPM Perspective

Sexting partners must negotiate how they manage their privacy rules in regard to sharing sexts. Individuals fear that sexts may be forwarded (Renfrow and Rollo), and in some cases, sext messages are nonconsensually forwarded to third parties (Drouin et al.). Thus, trust and privacy when sexting cannot be guaranteed, which contributes to the view that sexting is inherently risky. However, sexts are always considered private information that should not be shared beyond the intended recipient, and the sharing of sexts creates a mutual understanding of trust between the partners, resulting in a shared privacy boundary (Hasinoff and Shepherd). In the current study, we argue that the CPM privacy rules apply to the potential sharing of sexts and keeping the messages private. Specifically, each relationship partner must learn to balance their privacy needs with their partners’ privacy needs (Petronio; Petronio and Caughlin). Over time, partners learn which sexting privacy rules are most valued by their partner after some failed privacy disclosures (i.e., instances where a partner shares without realizing it invades their partner’s privacy).

Moreover, CPM differentiates between various privacy and disclosure boundaries: “while communication is the vehicle by which we are social, management of privacy is the mechanism that balances individual identity with social interaction” (Petronio 332). For instance, there are personal boundaries (i.e., information that an individual holds) and collective boundaries (i.e., information stored between two or more people). These boundary limits are controlled by privacy rules that are enacted based on a variety of social, cultural, and personal norms (Petronio and Caughlin). Moreover, boundary coordination takes place when individuals manage their boundaries well (Petronio). In particular, the boundary limits and boundary coordination of CPM are two important principles involved in sexting behaviors. Because of this, our study focuses on individuals who send texts who also believe that it is never okay to share sexts.

As noted, individuals send sexts for a variety of reasons. Some scholars suggest that sexting is most important to consider during adolescents’ development when they begin dating and forming romantic relationships, but others suggest that sexting is a form of self-disclosure, relational maintenance, or possibly even a form of sexual agency (Van Ouytsel et al.). In a comprehensive review of the literature on sexting, Cooper et al. noted that research primarily focused on the prevalence of sexting and the characteristics of people who sext, and far less research focuses on motivational factors of sexting. In an examination of the effects of individual motives, CPM practices (through boundary permeability and boundary ownership), and privacy concerns on Facebook self-disclosure, researchers found that CPM practices influence the amount and depth of self-disclosure (Chennamaneni and Taneja). Importantly, motivations for self-disclosure, in general, and sexting, in particular, are primarily relational in nature and can be either approach or avoidance oriented (Impett et al.). What follows is a discussion of these two forms of motivations related to intimate partner self-disclosure.

Avoidance Motives

Avoidance motives include relational acts such as avoiding conflict, keeping the partner from becoming upset, and preventing the partner from losing interest (Impett et al.). Most research on social media sites has focused primarily on privacy as it relates to Facebook users, which indicates that “the field’s collective understanding of users’ attitudes about social media privacy and corporate policies is very limited outside the Facebook context” (Stoycheff et al. 7). In the past, the primary medium for sexting has been through SMS text messages (Drouin et al., Ringrose and Barajas); however, other mediums such as applications like Snapchat are now used for sexting (Van Ouytsel et al.). Compared to traditional sexting using SMS, sexting using new media poses unique challenges to privacy. In a qualitative assessment, individuals reported that as a consequence of sexting, the message could be used as blackmail or revenge (Van Ouytsel et al.). Further, adolescents believe that sexting through smartphone applications is less risky than sexting through other mediums (Van Ouytsel et al.) and that trust in the message recipient was higher on mobile phones than it was for other mediums (Zemmels and Khey). Therefore, the perception of risk is hypothesized to be associated with more avoidance motives and negatively influence sexting experiences.

Hypothesis 1: The perception of risk moderates the relationship between avoidance motives and having a recent positive sexting experience among study participants who believed it was never okay to share sexts.

Privacy and trust are prerequisites for self-disclosure—in the current study, the self-disclosures are private sext messages. Privacy is defined as the “feeling that one has the right to own private information, either personally or collectively” (Petronio 6). As such, privacy is a “necessary condition that one protects or gives up through disclosure” (Petronio 14). Thus, privacy and trust are important correlates of CPM constructs due to the perception of negative consequences, rejection, and privacy loss to regulate self-disclosure (Waters and Ackerman). Therefore, we argue that trust will be associated with fewer avoidance motives and improve sexting experiences.

Hypothesis 2: The perception of partner trust moderates the relationship between avoidance motives and having a positive recent sexting experience among study participants who believed it was never okay to share sexts.

Approach Motives

Approach motives include relational acts such as promoting intimacy in the relationship, expressing love for the partner, pursuing each partner’s own sexual pleasure, and feeling self-satisfaction (Impett et al.). The most prevalent motivations for sexting include sexting as a form of flirting or gaining romantic attention, sexting within romantic relationships, sexting as an experimental adolescent phase, sexting because their partner pressured them to sext (Cooper et al.), and sexting as intention to flirt, as a sign of trust, and as a gift to their romantic partner (Van Ouytsel et al.). Aside from being pressured to sext, these motivations collectively suggest that sexting serves as a way to increase trust and commitment within intimate relationships. However, even being pressured to sext is a prevalent, albeit negative, motivator for sexting. This provides support for the idea that sexting functions as a form of self-disclosure and as a way to promote intimacy (Van Ouytsel et al.).

Given the heightened privacy concern and ease of distributing messages via new media, it is important to understand the perceived risks of sexting on new media. Petronio argues that privacy boundaries reduce risk when sharing private information. In this sense, boundary ownership refers to the responsibilities and rights co-owners have for the release of mutual, co-owned private information. Boundary permeability refers to how much mutual, co-owned private information is okay to share with a third party (Petronio). During a sexting encounter, boundary-management rules aid individuals by maximizing the benefits of self-disclosure while also minimizing the risks of disclosing private information. Because of this, it is expected that there will be less risk associated with sexting when approach motives are used, since those who use approach motives are already willing to sext and engage in boundary management. Therefore, we argue that less perceived risk will be associated with more approach motives and better sexting experiences.

Hypothesis 3: The perception of risk moderates the relationship between approach motives and having a recent positive sexting experience among study participants who believed it was never okay to share sexts.

Furthermore, trust plays a crucial role in understanding when individuals choose to disclose personal and private information with others (Chen and Sharma, Joinson et al., Metzger). Trust, defined as the “expectation that the other party will act predictably, will fulfill its obligations, and will behave fairly even when the possibility of opportunism exists” (Chen and Sharma 271), has also been found to be “a precondition for self-disclosure because it reduces the perceived risks involved in revealing private information” (Metzger 4). We argue that trust is also a precondition for privacy, because if you trust someone, you are more likely to tell them secrets and share private information (or sext) with them. Therefore, more trust is predicted to be associated with more approach motives and improve sexting experiences.

Hypothesis 4: The perception of partner trust moderates the relationship between approach motives and having a recent positive sexting experience among study participants who believed it was never okay to share sexts.

Message Permanence

Some characteristics of mediated environments including anonymity and the absence of nonverbal cues facilitate more frequent, intimate disclosures (Jiang et al., Tidwell and Walther). Specifically, “social media affordances reflect users’ perceptions of media utility in supporting social practices” (Bazarova and Choi 639). There are four affordances in social media: data permanence, communal visibility of social information and communication, message editability, and associations between individuals, as well as between a message and its creator (Bazarova and Choi). Shared privacy boundaries may vary based on the media’s permanence. Cavalcanti et al. found that Snapchat users adopted collaborative practice rules, as well as social rules to prevent feelings of loss after messages disappeared and to ensure their content was saved. These ephemeral messages are mediated messages that disappear after a set amount of time—allowing users to share temporary moments instead of posting images permanently. Ephemeral messages allow the sender of the message some degree of choice about the duration of the availability of the message before deletion. On some platforms, like Snapchat, messages disappear after a set amount of time, which leads users to perceive the channel as more personalized and enables the users to share more spontaneous, everyday self-disclosures with trusted relationship partners (Bayer et al.). Therefore, we predict that less permanent messages should strengthen the relationship between approach motives and positive sexting experiences.

Hypothesis 5: The perception of message permanence moderates the relationship between approach motives and having a positive recent sexting experience among study participants who believed it was never okay to share sexts.

On social media sites, the frequency of social media use increases online self-disclosure (Chennamaneni and Taneja). Sexting frequency increases with age and gender, such that people send and receive more sexts as they get older, and women are more likely to receive sexts from strangers and are more likely to be pressured to send sexts (Burén and Lunde). Consequently, the degree of ephemerality of various platforms may influence people’s choices about whether to use a certain platform for sexting communication. Further, individuals tend to prefer ephemeral communication because these platforms create spaces for fun, spontaneous interactions, and their ephemeral nature promotes privacy (Cavalcanti et al.). In the current study, we argue that platforms with high degrees of ephemerality could also reduce risk to sexters. Therefore, it is posited that risk will improve the relationship between approach motives and positive sexting experience when messages are perceived as less permanent, especially for those who believe sext messages should never be shared.

Hypothesis 6: A mediated moderation model exists whereby message permanence moderates the relationship between approach motives and perceptions of risk, and risk mediates the relationship between approach motives and sexting experiences among the subset of individuals who believed it was never okay to share sexts.

Method

A cross-sectional survey was used to examine individuals’ motivations for sexting using new media and their perceptions of privacy and the consequences of sexting. Measures were included for demographic information, sexting behaviors, modality trust, partner trust, privacy, risk, and message permanence.

Participants

Participants (N = 154) were recruited from undergraduate communication courses at a large Midwestern university, and they received a unit of research credit for their participation. To be eligible to participate, participants needed to be at least 18 years old and have sexted before. The first question of the survey asked if participants had sexted before based on the following definition: “For the purposes of this study, we define sexting as the creation and sharing of sexual or sexually suggestive messages, images, or videos through mediated communication (e.g., the sending of sexts through texts, Snapchat, Instagram, etc.).” If participants had never sexted before, they were offered an alternative assignment; a total of 29 students chose to complete the alternative assignment, indicating that the percentage of the sample who sext was about 84.13%. Participants were also asked to report their sexting frequency. Options ranged from “about every six months” (n = 19, 12.3%), “once every few months” (n = 31, 20.1%), “once a month” (n = 17, 11.0%), “every few weeks” (n = 25, 16.2%), “every other week” (n = 12, 7.8%), “once a week” (n = 16, 10.4%), “a few times a week” (n = 23, 14.9%), “almost every day” (n = 6, 3.9%), and “every day” (n = 4, 2.6%).

More women (n = 111, 72.1%) participated in the survey than men (n = 42, 27.3%), and participants were from the following ethnic backgrounds: white (n = 106, 68.8%), Black or African American (n = 14, 9.1%), American Indian or Alaska Native (n = 1, 0.6%), Asian (n = 13, 8.4%), and other (n = 19, 12.3%). Participants ranged in age from 18 to 55, with the average age of 22 (SD = .487). The following sexual orientations were reported by participants: heterosexual (n = 130, 84.4%), homosexual (n = 5, 3.2%), bisexual (n = 14, 9.1%), or other (n = 5, 3.2%). Participants reported knowing the person they sexted with from less than three days to more than five years, and the average length was three to six months (SD = 3.182). Most participants labeled this relationship as a romantic relationship (n = 109, 70.8%), while others labeled it as “friends with benefits” (n = 30, 19.5%), “friends” (n = 11, 7.1%), or other (n = 4, 3.1%). Responses for the other category included “casual dating,” “it’s complicated,” “no relation,” and “past romantic relationship.” All responses to these questions are included in the analyses.

Measures

Modality choice

Respondents were asked which modalities they used to sext most often based on Van Ouytsel et al.’s findings. The three most popular platforms used for sexting in this study included Snapchat (n = 90, 58.4%), SMS/texting (n = 26, 16.9%), and iMessage (n = 23, 14.9%). Participants’ top modality for sexting was then coded based on varying levels of message longevity: anonymous, ephemeral, dating, traditional, and video. In anonymous chat applications (n = 35, 22.7%), the sender and receiver are only known to one another, and messages disappear after a set amount of time (e.g., Kik and Whisper). In ephemeral applications (n = 58, 37.7%), messages disappear after a set amount of time (e.g., Snapchat and WhatsApp). In disappearing/dating applications (n = 4, 2.6%) messages go away once unmatched (e.g., dating applications like Tinder and Bumble). In traditional SMS messaging (including iMessage), messages cannot be deleted after they are sent (n = 48, 31.2%). Finally, video-messaging or video-calling applications were also relatively common (n = 7, 4.5%).

Privacy

Privacy was assessed using Hasinoff and Shepard’s measure of privacy norms. The measure consists of seven sexting scenarios and asks yes-or-no questions about whether it is okay for the recipient to distribute the sexting image under different circumstances. The different scenarios included asking whether it was okay for the receiver of sext to share a photo if: the couple has been together for one year, the couple has been together for one week, the receiver shows the sext to someone in person (on the receiver’s phone), it is shared through a private messaging platform, the photo has a lock placed on it by the sender, and it does not have a lock on it (Hasinoff and Shepherd). Whether it was okay to screenshot a photo sent via Snapchat and whether it was okay to share a screenshotted photo were also added possible scenarios. Response options included “yes, it is okay to share” and “no, it is not okay to share.” The nine questions demonstrated relatively high internal reliability (a = .847).

Sexting behaviors

Burén and Lunde measured sexting behaviors based on 12 items based on this study’s following definition of sexting (same as the one used previously in the survey): “for the purposes of this study, we define sexting as the creation and sharing of sexual or sexually suggestive messages, images, or videos through mediated communication (e.g., the sending of sexts through texts, Snapchat, Instagram, etc.)”. Respondents were asked whether they have received and sent sexts from (a) a girlfriend/boyfriend/romantic partner, (b) friends/peers, (c) someone they met online, and (d) someone they had never met in person (Burén and Lunde). The measure also asked how they would rate their most recent sexting experience, with options ranging from “very positive” to “very negative” and whether they felt pressured to send sexts with options ranging from “never” to “very often.”

Risk

The perceived consequences of sexting were assessed on the same scale and included the following prompt—“Do you worry about the following possible consequences of sexting”—to which participants responded to six statements: “Forwarding the photograph or publishing it online (i.e. on a social networking site),” “Showing the photograph to others,” “Not forwarding or showing the photograph but telling others about it,” “Exposing the photograph as revenge after a breakup,” “Blackmailing the sender of the photograph,” and “other” (Van Ouytsel et al., 2017). Items were assessed on a five-point Likert scale with options ranging from “never” to “always.” The six items were averaged for a total risk score, and the items demonstrated high internal reliability (a = .965).

Approach and avoidance motives

The approach motives for sexting were assessed using Impett et al.’s Sex Motives Measure. Participants responded how important each item was to them in their decision to sext. The first five items were added to create the approach motives measures. These items included “to pursue my own sexual pleasure,” “to feel good about myself,” “to please my partner,” “to promote intimacy in my relationship,” and “to express love for my partner.” Together, these five items demonstrated good internal reliability (a = .811). The avoidance-motives measure was created using the last four items of the same scale, which included the statements “to avoid conflict in my relationship,” “to prevent my partner from becoming upset,” “to prevent my partner from getting angry at me,” and “to prevent my partner from losing interest in me.” All statements were assessed on a five-point Likert scale with options ranging from “not at all important” to “extremely important.” Together, these four items demonstrated good internal reliability (a = .929).

Message permanence

Questions were developed based on Cavalcanti et al. that asked about participants’ perceptions of message permanence. Participants indicated on a five-point Likert scale how much they agreed with the following five statements: “It is important to me that platforms delete my sexts after a period of time (e.g., Snapchat),” “I am more likely to sext if I know the message will go away after a set amount of time,” “It is less risky to send sexts through platforms that delete messages after a set amount of time,” “It is more private to sext through platforms that delete messages after a set amount of time,” and “I have more trust in platforms that remove messages after they are received.” Lower scores indicate higher importance of message permanence, and higher scores indicate higher importance of message ephemerality. Together, these five items demonstrated good internal reliability (a = .860).

Trust

Trust was measured based on an adapted version of Fogel and Nehmad’s trust in SNS scales. Fogel and Nehmad’s scales for Facebook trust and social network trust were adapted to refer to the application used for sexting and mobile applications in general, and their measure for cellular trust stayed the same, as it focuses on the trust they have in the recipient of the message. The last four questions in the scale indicated trust for the partner; each group was averaged to get partner trust values. The questions were measured on a five-point Likert scale, and respondents indicated how much they agreed with each statement. Higher scores indicated more trustworthiness (Fogel and Nehmad). The items for partner trust included “the people that I send pictures/video to are trustworthy,” “I can count on those people to protect my privacy,” “I can count on those people to protect my personal information from unauthorized use,” and “those people can be relied on to keep their promises.” Reliability was high for partner trust (a = .979)

Analysis and Results

This study focuses on how partner trust, message permanence, and risk influence the relationship between avoidance or approach motivations for sexting and the experience of the participants’ last sext. Due to our focus on privacy management, we analyzed the participants who indicated that it was never okay to share sexts. Correlations between all study variables are presented in Table 1, and correlations between study variables in the subset of participants who believed it was never okay to share sexts are presented in Table 2. As expected, the correlations are stronger for those who believed it was never okay to share sexts.

Table 1.

Significant Correlations

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Partner Trust | -0.151 | -0.057 | .178* | -0.038 | 0.084 | -.343** | |

| 2. Permanence | -0.038 | -0.073 | -.170* | 0.067 | .194* | ||

| 3. Approach Motives | 0.138 | -0.008 | 0.092 | .179* | |||

| 4. Avoid Motives | 0.011 | .180* | -.341** | ||||

| 5. Modality Type | -0.090 | -.052 | |||||

| 6. Privacy | -.369** | ||||||

| 7. Risk |

*. Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

**. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

N = 154.

Table 2

Subset Correlations

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Permanence | .251* | -0.237 | 0.074 | 0.178 | -.210* | -0.136 | .277** | |

| 2. Risk | -0.352 | -.259* | .278** | -.427** | -.233* | .347** | ||

| 3. Motivation (b) | 0.230 | -0.110 | 0.250 | 0.340 | -0.247 | |||

| 4. Approach motives (r) | 0.107 | 0.167 | .258* | -0.069 | ||||

| 5. Avoidance motives (r) | -0.193 | 0.122 | .229* | |||||

| 6. Partner trust | .268** | -0.186 | ||||||

| 7. Sexting experience | -0.176 | |||||||

| 8. Pressure to sext |

*. Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

**. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

N = 94

(b) indicates behavioral motivations; (r) indicates relational motivations

Among the subset of participants who indicated that it is never okay to share sexts, approach motives are significantly correlated with risk (-.259) and how the participant rated their last sexting experience (r = .258). Avoidance motives are significantly correlated with risk (r = .278) and pressure to sext (r = .229). Further, permanence (r = .277) and risk (r = .347) are correlated with feeling pressured to sext, and risk (r = -.233) and trust (r = .268) are correlated with how the participant rated their last sexting experience. Because the subsample includes only the participants who indicated that it is never okay to share sexts, the correlations demonstrate that individuals only share their private information (i.e., sexts) if they are motivated to do so, and they manage their privacy boundaries by choosing less permanent modalities. Notably, participants seemed to recognize the increased risk involved in being pressured to sext, because they were more likely to prefer ephemeral platforms when pressured to sext. This finding shows that sexting can be seen as a somewhat deviant behavior, but participants are more likely to consider the ephemerality of the platform and the risk involved in participating in such a behavior.

Moderation Analyses

The significant correlations (see Tables 1 and 2) indicate the relationship between motivations for sexting and the participants’ sexting experiences is influenced by trust, message permanence, and/or risk. Therefore, we proceeded to test our moderation hypotheses. The first eight moderations were tested using Hayes’ PROCESS extension for SPSS (using Model 1). In moderation analysis, the significant interaction indicates a significant moderation effect (Hayes, “Hacking PROCESS”).

Hypothesis 1 states the perception of risk moderates the relationship between avoidance motives and having a recent positive sexting experience among study participants who believed it was never okay to share sexts (n = 93). The results of the moderation demonstrate that perception of risk significantly moderates the relationship between avoidance motives and positive sexting experiences, F (3, 89) = 4.73, R = .371, p = .004. Perception of risk (β = -.413, p = .001) was a significant predictor in the model, and the interaction between risk and avoidance motives was also significant (β = .026, p = .001). Therefore, lesser perceptions of risk are related to perceptions of positive experiences, and the effect depends on the perception of risk (Hayes, “Introduction to Mediation”). These variables accounted for a significant amount of the variance in sexting experiences, Δ R2 = .048, Δ F (1, 89) = 4.92, p = .029, β = .026, t (93) = 2.22, p = .002. In other words, among those who believe it is never okay to share sexts, the perception of risk significantly moderates the relationship between avoidance motives and sexting experience, meaning that when individuals have avoidance motives, they perceive more risk, and more risk changes their experiences of sexting in a negative way.

Hypothesis 2 states that the perception of partner trust moderates the relationship between avoidance motives and having a positive recent sexting experience among study participants who believed it was never okay to share sexts (n = 94). The results of the moderation demonstrate that trust moderates the relationship between avoidance motives and sexting experiences, F (3, 90) = 3.96, R = .341, p = .010. Trust (β = .307, p = .014) was a significant predictor in the model; however, the interaction between avoidance motives and trust was not significant (β = -.016, p = .251). Therefore, Hypothesis 2 was not significant.

Hypothesis 3 states that the perception of risk moderates the relationship between approach motives and having a recent positive sexting experience among study participants who believed it was never okay to share sexts (n = 91). The results of the moderation demonstrate that perception of risk significantly moderates the relationship between approach motives and positive sexting experiences, F (3, 87) = 5.61, R = .403, p = .002. Perception of risk (β = -.705, p = .002) was a significant predictor in the model, and the interaction between risk and approach motives was also significant (β = .033, p = .023). Therefore, lesser perceptions of risk are related to perceptions of positive experiences, and the effect depends on the perception of risk (Hayes, “Introduction to Mediation”). These variables accounted for a significant amount of the variance in sexting experiences, Δ R2 = .052, Δ F (1, 87) = 5.37, p = .023, β = .033, t (87) = 2.32, p = .023. In other words, among those who believe it is never okay to share sexts, the perception of risk significantly moderates the relationship between approach motives and sexting experience, meaning that when individuals have approach motives, they perceive less risk, and less risk changes their experiences of sexting in a positive way.

Hypothesis 4 states that the perception of partner trust moderates the relationship between approach motives and having a recent positive sexting experience among study participants who believed it was never okay to share sexts (n = 92). The results of the moderation demonstrate that trust significantly moderates the relationship between approach motives and sexting experience, F (3, 88) = 7.20, R = .444, p = .000. Trust (β = .881, p = .001) and approach motives (β = .180, p = .001) were significant predictors in the model, as well as the interaction between the two (β = -.049, p = .006). Therefore, approach motives are related to sexting experiences throughout the model, and the effect depends on the perception of risk. These variables accounted for a significant amount of the variance in permanence, Δ R2 = .073, Δ F (1, 88) = 13.42, p = .006, β = -.039, t (92) = -2.83, p = .006. In other words, the perception of risk significantly moderates the relationship between approach motives and sexting experiences. This means that individuals perceive more positive sexting experiences when they have approach motives and perceive their partner as more trustworthy.

Hypothesis 5 states that the perception of message permanence moderates the relationship between approach motives and having a positive recent sexting experience among study participants who believed it was never okay to share sexts (n = 92). The results of the moderation demonstrate that trust moderates the relationship between avoidance motives and sexting experiences, F (3, 88) = 3.32, R = .319, p = .023. However, no variables in the model were significant, and the interaction between approach motives and permanence was not significant (β = .025, p = .290). Therefore, Hypothesis 5 was not significant.

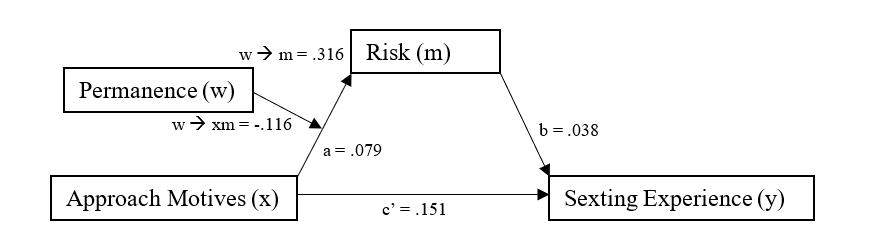

Hypothesis 6 uses a mediated moderation model where message permanence moderates the relationship between approach motives and perceptions of risk, and risk mediates the relationship between approach motives and sexting experiences among the subset of individuals who believed it was never okay to share sexts. Figure 1 presents the model used for Hypothesis 6. The model controls for the possibility that individuals may have both approach and avoidance motives by including avoidance motives as a covariate (Impett et al.).

Figure 1. Mediated Moderation Model

To determine significance of the mediated-moderation model, the moderation first must be significant, then the indirect effect should be more significant than the direct effect, and finally the confidence interval for the moderated mediation index should not include zero. First, permanence significantly moderates the relationship between approach motives and risk, F (4, 86) = 8.88, R = .541, p = .000. Both approach motives (β = -.079, p = .012) and permanence (β = .316, p = .021) , with a significant interaction (β = -.116, p = .001), meaning that the variables accounted for a significant amount of the variance in risk, Δ R2 = .093, Δ F (1, 86) = 11.32, t (86) = -3.36, p = .001. Second, the nonsignificance of the direct effect indicates the presence of a mediation, c’ t = 1.78, p > .05. The significance of the indirect effects (C1 = -.005, C2 = .016, C3 = .034) also indicates the presence of a mediation. Finally, the moderated mediation index (MMI) significantly differs from zero and indicates that the three indirect effects are significantly different from each other and that they are significantly different from the direct effect, MMI = .018, C.I. = .001–.042.

The results from Hypothesis 6 show that when an individual has approach motivations for sexting, the perception of risk mediates the relationship between approach motives and sexting experience, and permanence moderates the relationship between approach motives and risk. In other words, individuals consider permanence as a mechanism to reduce risk when they have approach motives and doing so reduces their perceived risk in sexting and improves their sexting experience.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to better understand how individuals’ motivations for sexting are influenced by trust, risk, and message permanence. To understand this relationship, we conducted a series of moderation analyses that culminated with a mediated moderation model. First, risk moderated the relationship between sexting experiences and both approach and avoidance motivations for sexting. Next, trust also moderated the relationship between approach motivations and sexting experiences. Third, risk moderated the relationship between message permanence and both approach and avoidance motivations for sexting. Fourth, a mediated moderation model demonstrated that message permanence moderated the relationship between approach motives and risk, and risk mediated the relationship between approach motives and sexting experiences. The implications of these findings are discussed next.

Minimizing Risk Regardless of Motivation

In the present study, risk moderated the relationship between avoidance motivations and sexting experiences, but trust and message permanence did not. When individuals experienced avoidance motivations for sexting, their sexting experience changed based on their perception of risk. When participants experienced avoidance motivations and high risk, they reported worse sexting experiences. We also found that risk and trust moderate the relationship between approach motivations and sexting experiences. In other words, the best sexting experiences for these participants occurred when three conditions were met: (a) intimate partners were motivated by relational goals, such as intimacy, affection, and sexual pleasure (i.e., approach motives; Impett et al.), (b) they perceived higher trust, and (c) they perceived less risk. These findings align with Petronio’s claim that the presence of privacy boundaries reduces risk when sharing private information. However, individuals are more likely to manage the risk of their private information being shared when they have approach motivations compared to when they have avoidance motives, as well as when there are perceptions of trust.

Permanence as a Mechanism for Privacy Management

Regardless of the type of motivation to sext, the relationship between motivation and message permanence is moderated by perceptions of risk. Further, when individuals experienced approach motivations for sexting, they considered the permanence of a message as a way to manage their perceptions of risk for sexting. Subsequently, their perceptions of reduced risk from using less permanent platforms led to improved sexting experiences. Thus, the perception of risk is certainly an important factor for sexting. This set of findings highlights that individuals are aware of the risk involved with sexting and actively look for ways to reduce this risk. One of the ways—as suggested by these findings—is to manage sexting risk related to the permanence of a platform.

Theoretical and Practical Implications

The findings from this study offer important theoretical insights about sexting. Sexting has commonly been framed as a deviant behavior (Lee et al.; Van Ouytsel et al.). However, the findings from this study demonstrate that individuals are motivated to sext for both approach and avoidance reasons, not simply as a means to engage in some form of deviant behavior. Risk is inherently involved with sexting, but individuals can use knowledge of technology affordances, in particular less permanent social media, to reduce this risk.

The findings from this study provide additional support for situating sexting within CPM. CPM deals with how individuals manage shared, private information (Child and Petronio). In mediated contexts, individuals have more capacity to manage this shared, private information because individuals are able to choose the modality they use for sexting, and each modality offers varying levels of permanence. By choosing a modality with less permanence (e.g., Snapchat), an individual is able to mitigate the risk involved with sexting because they have more control and ability to manage how their sexts are shared than if they chose a more permanent modality (e.g., traditional text messaging). From a CPM perspective (Petronio), the findings of this study demonstrate that message permanence changed the relationship between approach motivations and risk, such that the privacy boundary created by reduced permanence reduced the risk of sharing private information. Message permanence and potentially other social media affordances could serve as mechanisms that individuals could harness in order to reduce the risk of sexting while improving their sexting experiences.

The current findings are useful for practitioners, because the findings could inform therapy recommendations, media literacy education, and intervention practices. Specifically, rather than focusing solely on the risks and consequences of sexting, practitioners should focus on ways to improve sexting experiences. As evidenced by the current data, people should, perhaps, be educated about how to manage the privacy boundaries involved in sexting by choosing less permanent social media for their sexting self-disclosures.

Limitations and Future Directions

While this study contributes to CPM in mediated contexts (Child et al.), some limitations and future directions also warrant further discussion. The focus of this study was on sexting; this meant that only those who had ever sexted completed the survey. We also only include within these analyses individuals who believed under no circumstances should sexts be forwarded. However, the inclusion of nonsexters may offer insights about why individuals choose to abstain from sexting. Individuals who abstain from sexting may think the risks of this form of sexual self-disclosure could never outweigh the benefits, or they may not be comfortable with sending sexts in the first place. Individuals who see viable reasons why sext messages should be forwarded would also add a layer of insight about private and risky sexual messages. Future research should examine how these groups differ—if at all—from those in this study.

This study relied on correlational data, single-item measures, and binary response types, which limited the completeness of our conclusions. Moreover, we relied on some measures that are not traditionally used within the self-disclosure context of sexting. The items and scales we use offered high internal reliability, which supports the strength of the findings. Future scholars should determine the validity of these scales in the self-disclosure context of sexting. However, scholars would benefit from specific measurement measures for the context of sexting, especially as they pertain to privacy and trust. However, we recognize the difficulty in such measurement development, as sexting communication is a self-disclosure that is continually developing in form, context, and norms. Further, the present study highlighted only one new media affordance—permanence. We encourage future researchers to consider how other affordances of new media impact the risk and experience of sexting.

This study was focused on the motive expression (i.e., an individual’s self-reported motivations for sexting) rather than the motive attribution (i.e., an individual’s perceptions of a partner’s motivations for sexting). Future research should attempt to remedy this by using a dyadic research paradigm to remedy this methodological design limitation. Finally, a longitudinal study (day to day or even week to week) would offer important insights about sexting in intimate relationships, specifically the impact of motivations for sexting over time.

Conclusion

The current study adds to Communication Privacy Management Theory (CPM) research in mediated contexts by demonstrating that certain media attributes serve as ways to manage privacy boundaries. Further, this study expands our understanding of sexting by highlighting that the motivations for sexting influence the overall sexting experience. The findings contribute to CPM in mediated contexts (Child et al.) by showing that privacy is a concern, but that individuals take steps and use tools like message permanence to manage their privacy boundaries by mitigating risk. As such, social media affordances, including visibility, associations, editability, and permanence, serve as mechanisms that individuals use to manage their privacy boundaries and control the sharing of their private information (i.e., sexts).

Works Cited

Angelides, Steven. “‘Technology, hormones, and stupidity’: The affective politics of teenage sexting.” Sexualities, vol. 16, no. 5-6, 2013, pp. 665–689. doi:10.1177/1363460713487289.

Bayer, Joseph B., et al. “Sharing the Small Moments: Ephemeral Social Interaction on Snapchat.” Information, Communication & Society, vol. 19, no. 7, July 2016, pp. 956–77. Crossref, doi:10.1080/1369118X.2015.1084349.

Bazarova, Natalya N., and Yoon Hyung Choi. “Self-Disclosure in Social Media: Extending the Functional Approach to Disclosure Motivations and Characteristics on Social Network Sites.” Journal of Communication, vol. 64, no. 4, Aug. 2014, pp. 635–57. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1111/jcom.12106.

Burén, Jonas, and Carolina Lunde. “Sexting among adolescents: A nuanced and gendered online challenge for young people.” Computers in Human Behavior, vol. 85, 2018, pp. 210–217. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2018.02.003.

Cavalcanti, Luiz Henrique C.B., et al. “Media, meaning, and context loss in ephemeral communication platforms: A qualitative investigation of Snapchat.” Proceedings of the 2017 ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing—CSCW 17, 2017, pp. 1934–1945. doi:10.1145/2998181.2998266.

Chen, Rui, and Sushil K. Sharma. “Self-Disclosure at Social Networking Sites: An Exploration through Relational Capitals.” Information Systems Frontiers, vol. 15, no. 2, Apr. 2013, pp. 269–78. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1007/s10796-011-9335-8.

Chennamaneni, Anitha, and Aakash Taneja. “Communication privacy management and self-disclosure on social media—A case of Facebook.” AMCIS, vol. 11, 2015.

Child, Jeffrey T., et al. “Blogging, Communication, and Privacy Management: Development of the Blogging Privacy Management Measure.” Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, vol. 60, no. 10, 2009, pp. 2079–94. Crossref, doi:10.1002/asi.21122.

Cooper, Karen, et al. “Adolescents and self-taken sexual images: A review of the literature.” Computers in Human Behavior, vol. 55, 2016, pp. 706–716. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2015.10.003.

Drouin, Michelle, et al. “Let’s talk about sexting, baby: Computer-mediated sexual behaviors among young adults.” Computers in Human Behavior, vol. 29, no. 5, 2013, pp. 25–30. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2012.12.030.

Fogel, Joshua, and Elham Nehmad. “Internet social network communities: Risk taking, trust, and privacy concerns.” Computers in Human Behavior, vol. 25, no. 1, 2009, pp. 153–160. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2008.08.006.

Hasinoff, Amy Adele. Sexting Panic: Rethinking Criminalization, Privacy, and Consent. University of Illinois Press, 2015.

Hasinoff, Amy Adele, and Tamara Shepherd. “Sexting in context: Privacy norms and expectations.” International Journal of Communication, vol. 8, 2014, pp. 2932–2415.

Hayes, Andrew F. Hacking PROCESS for Estimation and Probing of Linear Moderation of Quadratic Effects and Quadratic Moderation of Linear Effects. 2017.

Hayes, Andrew F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. 2nd ed., The Guilford Press, 2018, http://afhayes.com/introduction-to-mediation-moderation-and-conditional-process-analysis.html.

Jiang, L. Crystal, et al. “The disclosure-intimacy link in computer-mediated communication: An attributional extension of the hyperpersonal model.” Human Communication Research, vol. 37, no. 1, 2010, pp. 58–77. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2958.2010.01393.x.

Jenkins, Elizabeth M., and Glen H. Stamp. “Sexting in the Public Domain: Competing Discourses in Online News Article Comments in the USA and the UK Involving Teenage Sexting.” Journal of Children and Media, vol. 12, no. 3, 2018, pp. 295–311. doi:10.1080/17482798.2018.1431556.

Joinson, Adam, et al. “Privacy, Trust, and Self-Disclosure Online.” Human-Computer Interaction, vol. 25, no. 1, Jan. 2010, pp. 1–24. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1080/07370020903586662.

Lee, Chang-Hun, et al. “Effects of self-control, social control, and social learning on sexting behavior among South Korean youths.” Youth & Society, vol. 48, no. 2, 2013, pp. 242–264. doi:10.1177/0044118×13490762.

Madigan, Sheri, et al. “Prevalence of multiple forms of sexting behavior among youth: A systematic review and meta-analysis.” JAMA Pediatrics, vol. 172, no. 4, 2018, p. 327–335. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.5314.

Metzger, Miriam J. “Privacy, Trust, and Disclosure: Exploring Barriers to Electronic Commerce.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, vol. 9, no. 4, 2004. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1111/j.1083-6101.2004.tb00292.x.

Petronio, Sandra. “Communication Boundary Management: A Theoretical Model of Managing Disclosure of Private Information between Marital Couples.” Communication Theory, vol. 1, no. 4, Nov. 1991, pp. 311–35. academic-oup-com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu, doi:10.1111/j.1468-2885.1991.tb00023.x.

Petronio, Sandra. Boundaries of Privacy: Dialectics of Disclosure. State University of New York Press, 2002.

Renfrow, Daniel G., and Elisabeth A. Rollo. “Sexting on campus: Minimizing perceived risks and neutralizing behaviors.” Deviant Behavior, vol. 35, no. 11, 2014, pp. 903–920. doi:10.1080/01639625.2014.897122.

Ringrose, Jessica, and Katarina Eriksson Barajas. “Gendered risks and opportunities? Exploring teen girls’ digitized sexual identities in postfeminist media contexts.” International Journal of Media & Cultural Politics, vol. 7, no. 2, Jan. 2011, pp. 121–138. doi:10.1386/macp.7.2.121_1.

Speno, Ashton Gerding, and Jennifer Stevens Aubrey. “Adolescent sexting: The roles of self-objectification and internalization of media ideals.” Psychology of Women Quarterly, vol. 43, no. 1, Sept. 2018, pp. 88–104. doi:10.1177/0361684318809383.

Stoycheff, Elizabeth, et al. “What have we learned about social media by studying Facebook? A decade in review.” New Media & Society, vol. 19, no. 6, June 2017, pp. 968–80. Crossref, doi:10.1177/1461444817695745.

Tidwell, Lisa Collins, and Joseph B. Walther. “Computer-mediated communication effects on disclosure, impressions, and interpersonal evaluations: Getting to know one another a bit at a time.” Human Communication Research, vol. 28, no. 3, 2002, pp. 317–348. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2958.2002.tb00811.x.

Van Ouytsel, Joris, et al. “Adolescent sexting from a social learning perspective.” Telematics and Informatics, vol. 34, no. 1, 2017, pp. 287–298. doi:10.1016/j.tele.2016.05.009.

Van Ouytsel, Joris, et al. “Sexting: Adolescents’ perceptions of the applications used for, motives for, and consequences of sexting.” Journal of Youth Studies, vol. 20, 2016, pp. 446–470. doi:10.1080/13676261.2016.1241865.

Walrave, Michel, et al. “Sharing and caring? The role of social media and privacy in sexting behaviour.” Sexting: Motives and Risk in Online Sexual Self-Presentation, edited by Michel Walrave et al., Springer International Publishing, 2018, pp. 1–17. Springer Link, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-71882-8_1.

Waters, Susan, and James Ackerman. “Exploring privacy management on Facebook: Motivations and perceived consequences of voluntary disclosure.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, vol. 17, no. 1, 2011, pp. 101–115. doi:10.1111/j.1083-6101.2011.01559.x.

Zemmels, David R., and David N. Khey. “Sharing of digital visual media: Privacy concerns and trust among young people.” American Journal of Criminal Justice, vol. 40, no. 2, 2014, pp. 285–302. doi:10.1007/s12103-014-9245-7.