When Janice Radway conducted her now-famous study of romance readers in the early 1980s, she found that all her respondents “cited the educational value of romances,” and she therefore concluded that they have a “penchant for geographical and historical accuracy” (108). Four decades later, another survey of romance readers found that they were still

concerned with authenticity. Writers of historical romance novels often go to great lengths to ensure that their stories are imbued with historically accurate details. […] For readers, “characters can be fictional, but major events and ways of living should be authentic … dress, diet, dances, customs, historic characters”. Portraying historical accuracy is appreciated by readers. (Hackett and Coughlan)

However, as Adrienne Shaw has suggested with regards to digital games that draw on history, “It is never enough to talk about accuracy or veracity when analyzing these constructions; much more is learned by looking at who is telling the story, how they are telling it, and what that demonstrates about what they find important” (6).

The person “who is telling the story” which is the focus of this essay is best-selling author Courtney Milan. She is a romance writer with unique insights into the extent to which some in the romance community will mobilise to protect a racist status quo. In 2019 she found herself

at the center of the implosion of the Romance Writers of America […]. A longtime board member, she had spent years trying to push RWA to take a stronger stance against racism and work harder to promote equity and inclusion within its ranks. Instead, in December, RWA informed Milan of sanctions against her as the result of a formal ethics complaint, suspending her membership and banning her for life from a leadership position. (Lenker)

Just a few months later, Milan had been vindicated and the RWA’s own future seemed precarious (Willingham; Ryan). The events had, however, clearly left an imprint on Milan and her work: The Duke Who Didn’t provides an alternative to the racist stereotype which will be discussed later in the essay and which was at the heart of the ethics complaint against her. Drawing on her own family history, it “has a lot to say about the experience of being an immigrant, of being the child of immigrants, and of being seen as a foreigner in one’s own country” (Catherine Heloise).

With regards to the “how” of Milan’s writing about the past, she has stated that

while I try to make sure that my books are historically accurate in the sense that the events could have happened, my books are not, and will never be, historically average. In fact, I lean towards the opposite—historically extraordinary.

I do that on purpose: I use the past as a crucible to explore the present. (“Fairytales”)

In this essay I demonstrate that Milan’s The Duke Who Didn’t, which was released on 22 September 2020, is a historical romance which uses “the past as a crucible” to explore present romance genre norms and the whiteness which underpins them. I show how, via the race of the characters, the deployment of carnivalesque elements, and the structure of the plot, The Duke Who Didn’t subverts reader expectations of historical romance novels. I analyse how the implausibility of a number of accepted romance tropes is highlighted, and how the novel includes historically accurate details which some readers may nonetheless find implausible. This juxtaposition, I argue, challenges readers to question whether demands for accuracy are deployed consistently, or whether they are, in fact, sometimes invoked in order to maintain the status quo in the genre. Finally, I explore how a plot line involving the recipe for a sauce is deployed to raise issues relating to cultural appropriation and identity, and how these issues are interwoven with Milan’s experience as a Chinese American.

Telling the Story: Setting, Characters, Tone, and Narrative Structure

The Duke Who Didn’t presents a challenge to some genre norms, a challenge which is perhaps made all the more salient because of how closely it adheres to others. In recent years historical romance has been dominated by nineteenth-century English settings and protagonists from the upper ranks of the aristocracy: when Jennifer Hallock examined the best-selling historicals published by RWA members between December 2017 and May 2018, she found that sixty-three percent of them were set in “19th century England,” and in the same period “over one-third of the top 20 Regency and Victorian romances on Amazon’s bestseller lists […] included either duke or duchess in their titles.”

Set in England in 1891, with a duke as its hero and in its title, Milan’s novel would appear to conform perfectly with the norms of its subgenre. However, Milan signals her awareness of the fact that her novel deviates from these norms when she introduces her hero, Jeremy Wentworth, the Duke of Lansing: “He was tall and dark and handsome. The perfect storybook hero, if storybook heroes had ever been half-Chinese” (Milan, The Duke ch. 1). While the statement ostensibly refers to “the English storybooks Chloe had read as a child” (Milan, The Duke ch. 1), it is also easily transferred to modern American popular romance novels, in which tall, dark, and handsome heroes are common but half-Chinese heroes are extremely rare. Jeremy is aware that he does not fit in: the English aunt who took charge of his upbringing “helped me understand that everyone else thought I was unsuitable” (Milan, The Duke ch. 13). However, as Jeremy observes,

It turns out, they were happy to laugh. They’ve always been happy to laugh with me. At Eton. At Oxford. Nobody wants me to be serious, but if I’m willing to have a little fun, well, they’re willing to play along. (Milan, The Duke ch. 13)

Perhaps Milan was experimenting to see if readers, too, would be willing to play along as she and Jeremy made them laugh. In tone the novel is, as stated by one reviewer, “whimsical, fun” (Finston). In the midst of what was by then a global pandemic, Milan hoped she could share with her readers some of the “joy” she had found while “writing this book” (“I’ve hit”).

Her mixing of humour and serious themes recalls Mikhail Bakhtin’s concept of the carnivalesque, which Robert Stam distinguishes from “ultimately less subversive categories such as ‘comedy’ and ‘play’” (85) because “The carnivalesque principle abolishes hierarchies, levels social classes, and creates another life free from conventional rules and restrictions. In carnival, all that is marginalized and excluded […] takes over the center in a liberating explosion of otherness” (Stam 86). The novel is literally set during a sort of carnival, the fictional Wedgeford Trials, a “daylong game,” held in the village of Wedgeford Down, which has “attracted people from all over Britain for centuries […]. Wedgeford was a village of mere hundreds, but for three days—the Trials themselves, and the days before and after—its population would swell to almost a thousand” (Milan, The Duke ch. 2). The village is transformed into a place where the usual social hierarchies do not exist: as Jeremy tells a “spoiled Eton” boy who has arrived for the Trials, “You’re used to people doing your bidding. […] Except that’s not how it works” in Wedgeford (Milan, The Duke ch. 2; ch. 5). Here it is the villagers whose decisions are final and whose knowledge is valued, and so, as in carnival, the period of the Trials constitutes a “temporary liberation from the prevailing truth and from the established order; it marked the suspension of all hierarchical rank, privileges, norms, and prohibitions” (Bakhtin 10).

Wedgeford’s “temporary liberation from the prevailing truth and from the established order” extends to the very structure of the novel itself. Drawing on “kishoutenketsu (in Japanese)” (“So”) Milan decided to depart from the “Western narrative structure” demanded by “Most RWA chapter contests” (“Also”) and which, “As a writer, the first four or five books, you just accept […] [t]his is the way it’s done” (Lenker). In The Duke Who Didn’t, however, Milan challenges the necessity of what Pamela Regis, in her influential account of the structure of the romance novel, termed a “point of ritual death” (35). According to Regis, this is an “essential element” (30) of the romance which “marks the moment in the narrative when the union between heroine and hero, the hoped-for resolution, seems absolutely impossible” (35). Milan, however, “felt like the thing I was being pushed to do didn’t work” (Lenker), and so in this romance, although Jeremy fears that his union with Chloe is “absolutely impossible” (Regis 35), “The thing that happens that would normally be the climactic moment of the book is not a dark moment” (Milan qtd. in Lenker). In other words, whereas in a romance which follows the conventions described by Regis the reader “responds to the peril, the mood, and to the repetition of the imagery of death” (Regis 36), Milan’s carnivalesque romance, while it does have Chloe comment that at this decisive moment Jeremy looks as though he is “about to pronounce a death sentence” (Milan, The Duke ch. 17) on her, has bathos replace the solemnity and fear of a ritual death. Here, “ritual death” merely leaves one protagonist temporarily “befuddled” (Milan, The Duke ch. 17) and then has the other wanting “to laugh with […] relief” (Milan, The Duke ch. 17).

Accuracy: Trials and Tropes

Given the carnivalesque setting and tone, it seems fitting that Milan’s novel appears to be playfully engaging with readers’ potential concerns about accuracy. Milan has often questioned readers’ invocations of historical accuracy, arguing that they may be used as a type of “gatekeeping in the form of objecting to the inclusion of marginalized people having a happy ever after” (“Historical”). Specifically with respect to The Duke Who Didn’t, she suggested that if readers questioned the ethnicity of her hero, it was they who needed to reflect:

If you’re wondering whether there was a half-Chinese duke in the nineteenth century, the answer is no, not that I’ve found. For every character I’ve ever created, I’ve made up names, titles, and multiple details about their family history, often quite elaborate, and rarely tracking any actual family. If you don’t ask questions about people making up family history for fiction—and most people are—but stop to question when that family history includes non-white people, I think it’s a great time to interrogate why that is your reaction. I’m not faulting anyone who has that reaction, because we do have to grow accustomed to things we aren’t used to. Just take the time to think through the possibility that fiction doesn’t need to have happened in reality. (“If”)

Milan, then, has been interrogating which elements of a work readers are likely to reject as implausible and which fantasy or invented elements they will leave unquestioned. Her carnivalesque The Duke Who Didn’t can perhaps be considered a continuation of that process as it subjects its readers to the literary equivalent of the Wedgeford Trials.

During the Trials, teams spend “a day frantically searching for tokens from the other teams” (Milan, The Duke ch. 4). These tokens are known as Wedgelots and are hidden “on the outskirts of town before the start of the Trials, and the first team to bring two Wedgelots (any two Wedgelots) onto their designated territory near the center won” (Milan, The Duke ch. 5). The complication is due to the fact that

Every team engaged in Frauds—the hiding of fake tokens.

Someone had called them Widgelots—so very like a Wedgelot, and yet not one. (Milan, The Duke ch. 5)

The Wedgelots are “painted every year with new designs that symbolized what had happened during the year prior” (Milan, The Duke ch. 5), and the Widgelots are painted “much like a real Wedgelot would have been—but for the white words that said ‘Not a real Wedgelot’ on one side” (Milan, The Duke ch. 7).

As I demonstrate later in this essay, the depiction of Chloe’s mother, a Chinese Hakka woman, can be understood, in part, as a reference to “what had happened during the year prior” (Milan, The Duke ch. 5) in Milan’s professional life. It can therefore be considered a Wedgelot. Since the events “during the year prior” revolved around a discussion of historical accuracy, and since this Wedgelot has its historical accuracy highlighted in an author’s note, it seems reasonable to extend the designation of Wedgelot to other elements of the novel which will appear inaccurate to some readers, but which are either historically accurate or, like Jeremy’s ancestry and the personality of Chloe’s mother, have been shaped by Milan’s historical research and are therefore invented but historically plausible. In contrast, there are other aspects of the plot whose implausibility is hinted at and then underscored over the course of the novel, and these can be considered Widgelots. In the Trials of historical accuracy, the aim is to correctly identify two deceptive plot elements (Widgelots), or at least avoid misidentifying any accurate elements (Wedgelots) as inaccurate Widgelots. If readers seize on Wedgelots and declare them to be historically inaccurate, while overlooking the presence of Widgelots, it is they, not Milan, who will have lost the Wedgeford Trials of historical accuracy.

In The Duke Who Didn’t, at least two romance “tropes” are present which can be considered Widgelots: “For the uninitiated, […] ‘The word “trope” has […] come to be used for describing commonly recurring literary and rhetorical devices, motifs or clichés in creative works’” (Davidson viii). In other words, the “trope” is an element which has been repeated over and over again, like the layers of paint on the Wedgeford tokens, which have accumulated “like a tree growing rings with every season” (Milan, The Duke ch. 5). The Duke Who Didn’t contains both the Big Secret and Only One Bed tropes. Precisely because they are so familiar, their presence may be overlooked until Milan underlines or reveals their implausibility.

Only One Bed

The Only One Bed trope, as its name suggests, involves protagonists finding themselves in a situation in which there is only one bed available. For obvious reasons, this can be used to precipitate sexual intimacy. The trope appears in The Duke Who Didn’t in a “just one room” (Milan, The Duke ch. 13) variant. On a short trip to Dover, Jeremy and Chloe fall from their horse and need “some rooms at the inn” in order to “clean up a bit while […] waiting” (Milan, The Duke ch. 13) for return transport to Wedgeford. Chloe, however, suggests that there may be “only one room in the inn” (Milan, The Duke ch. 13). This suggestion is “so absurd” (Milan, The Duke ch. 13) that Jeremy can only blink with astonishment and ask Chloe why she is planning for such an “unlikely possibility” (Milan, The Duke ch. 13). In case a reader has failed to notice the implausibility of the trope in this context, he even goes on to ask, “Doesn’t that ‘just one room’ thing only happen in stories?” (Milan, The Duke ch. 13). Unrealistic though it may be, it certainly does happen in stories, and as Chloe points out to Jeremy, “If you’ve read the stories, you know what you are supposed to say. If there’s only one room, we could share the room. Together” (Milan, The Duke ch. 13) and consider it “fate and the right thing to do” (Milan, The Duke ch. 14). She then proceeds to think to herself that “Fate was precisely what she made of it” (Milan, The Duke ch. 14) and bribes the innkeeper into agreeing that there is “only one room” (Milan, The Duke ch. 14) available.

Chloe and Jeremy’s conversation thus reveals the role of the trope: to make the plot development in which the protagonists are forced into close physical proximity appear inevitable. Readers are usually complicit in the acceptance of this kind of literary “fate”: coincidences and other implausibilities can pass unchallenged if they are accepted tropes or norms of the genre. By making the implausibility of the Only One Bed trope explicit here, however, Milan perhaps indicates that if readers are looking for elements of the novel which are unrealistic, this should be high on their list.

The Big Secret

Milan is more subtle in her deployment of the trope of the Big Secret, but even here she seems to offer a metafictional hint when she has Chloe accuse Jeremy of “setting up an interesting story, not telling me all the relevant information, and tricking me so that I end up listening to you when I have no intention of doing so” (Milan, The Duke ch. 1). Certainly Milan herself is telling “an interesting story,” and she delays the revelation of some of “the relevant information,” so she could therefore be considered to be engaged in “tricking” the reader with regards to the Big Secret. The secret involves Jeremy being “in love with a woman who had no idea who he actually was”: “he was the Duke of Lansing and she had absolutely no idea” (Milan, The Duke ch. 1). The reader is told in the first chapter that the secrecy around Jeremy’s true identity dated from his first visit to Wedgeford, at the age of twelve, when he “had just misled” (Milan, The Duke ch. 1) the villagers about who he was, and by the

second year he’d visited, he had been having too much fun to ruin it by forcing everyone to become stuffy and bow to him and call him “Your Grace.” It had been impossible to hide the fact that he had means. His clothing, his accent, his manners, his ability to patronize businesses in Wedgeford … these were all too indicative of his class. But it was easy enough to misdirect. Nobody saw a half-Chinese boy of thirteen and thought, “By George, that child must be a duke.” (Milan, The Duke ch. 1)

This reasoning seems logical to Jeremy and will probably also seem so to the reader, given that historical romance can easily accommodate a Lost Heir, albeit such a character type has not hitherto tended to be presented in the guise of “a half-Chinese boy of thirteen.”

However, the Big Secret is a Widgelot hiding in plain sight. Its lack of realism is revealed in stages. First, Mr. Fong, Chloe’s father, reproaches Jeremy for having “neglected to mention the fact that you’re the Duke of Lansing” (Milan, The Duke ch. 8) and, when Jeremy asks how he could know, responds

“You are aware that I obtain additional funds by serving as a chef on occasion? […] People talk,” Mr. Fong said simply. “I’m Chinese. They think that all Chinese people know one another. More than half a dozen have asked me if I know the half-Chinese Duke of Lansing.” (Milan, The Duke ch. 8)

Later, Jeremy breaks the news to Chloe, only for her to point out that, as her father’s comments have already suggested, it would be almost impossible for anyone in Wedgeford to have remained unaware of Jeremy’s true identity given that white people

think all Chinese people know each other. There is precisely one half-Chinese duke in all of Britain… and you somehow think that the village of Wedgeford wouldn’t be continually informed of his existence? […] You cut a ribbon in the May Day parade in London last year. There were tens of thousands of people in the crowd! Did you think, in that massive assembly, that there was absolutely nobody from Wedgeford? (Milan, The Duke ch. 17)

At this point, a reader who has been tricked by this Widgelot may feel almost as foolish as Jeremy. In true carnivalesque manner, expectations have been undercut and the genre’s “established order” has been undermined by the explanation about the trope’s lack of realism. Meanwhile, this same reader may have spent some time misidentifying Wedgelots as Widgelots.

A Stationery Approach to Historical Accuracy

Milan hides a Wedgelot in the very first sentence of the novel, as “Chloe Fong retrieved her board clip from beneath her arm on a fateful spring dawn, not realizing that calamity was about to befall her carefully ordered list” (Milan, The Duke ch. 1). This “board clip” is Chloe’s

most prized possession: a thin metal, light enough to be carried everywhere and yet stiff enough to be used as a makeshift writing desk. It had been a gift from her father, handed over gruffly after he returned from business one day. A newfangled clip, a metal holder that snapped into place by means of a spring mechanism, trapped sheets of paper against the writing surface, with room for a pencil as well. It was the perfect invention if one made a daily list and consulted it regularly.

Chloe, of course, did. (Milan, The Duke ch. 1)

The term “board clip” is unusual enough to catch the attention of readers, including one named Emgeeze, who left a review at Amazon in which they referred to it as an “irritating little inaccuracy: what is a board clip? A Google search says that the clipboard was invented in 1907, and I can find no record of it being called a board clip at any point. That’s some pretty stupid-sounding ye olde talk….” The board clip, however, is entirely historically accurate.

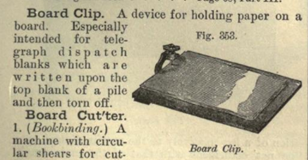

Knight’s New Mechanical Dictionary, which dates from 1884, describes the board clip as being “Especially intended for telegraph dispatch blanks which are written upon the top blank of a pile and then torn off” (Knight 113). This entry is accompanied by an illustration which does not precisely match the description of Chloe’s board clip.

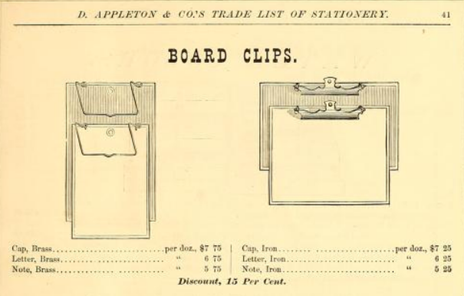

However, this was not the only style of board clip to be produced in the years preceding 1891. Two different types of board clip appear in D. Appleton & Company’s 1869 Illustrated Trade List of Domestic and Foreign Stationery (41).

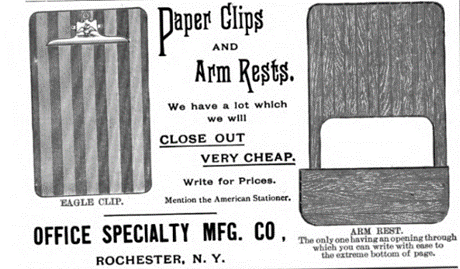

The second style illustrated there resembles the “Eagle Clip,” advertised in 1890 in The American Stationer (9), a year before the opening of the novel.

Both of these board clips appear to match Chloe’s relatively closely, as they seem to feature “a spring mechanism” (Milan, The Duke ch. 1). Moreover, the illustration in the Appleton catalogue, in particular, suggests that the movable part of the clip is curved, thus permitting it to trap “sheets of paper against the writing surface, with room for a pencil as well” (Milan, The Duke ch. 1).

Since the examples above are all from the US, however, and the novel is set in England, it seems important to include a resource to which Milan herself has referred: “The British Newspaper Archive [which] has newspapers from every part of Britain” (Luther). If one searches this archive, one can indeed find mentions of board clips. They feature among the “mercantile and office stationery” advertised by Thomas Wall in The Wigan Observer and District Advertiser on 26 January 1887, and on 16 October 1880, the Barnsley Chronicle published a list of “Stationery and Sundries kept in stock at ‘Chronicle’ Office, Barnsley,” which includes both “Board Clips” in quarto and foolscap sizes (7) and “American Gold Pencils.” The latter suggests that American stationery was imported into the UK, while Appleton’s list also provides an indication that there was transatlantic trade in stationery: that company was based in New York and the title page of their catalogue proclaims that they are “importers of fine English writing papers.”

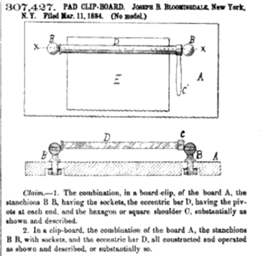

As is apparent from the “pad clip-board” patented by Joseph B. Bloomingdale in 1884 (United States Patent Office 372), it does appear that the “board clip” could, even in this period, be referred to as a “clip-board.”

However, the evidence from the British Newspaper Archive demonstrates that the term “board clip” was in use in the UK in the period in which Milan’s novel was set, and illustrations of late-nineteenth-century board clips exist which match the description given in the novel. While I have not been able to ascertain the designs of board clips typically available in the UK, it is possible that US board clips could have been imported into England or that clips of a design similar to those in the US were manufactured in the UK. In rejecting the accuracy of the “board clip,” therefore, Emgeeze has wrongly identified this Wedgelot as a Widgelot.

Emgeeze’s disbelief in the presence of what must have been a well-researched element of Milan’s novel demonstrates that

authenticity, as it applies to the historical novel, is not simply presenting the past factually. Authenticity is a negotiation between the evidence available to the writer, the reader’s existing understanding of the period and the imaginative power of the author, which combined, can only present the spirit of an era rather than its actuality. (Stocker 310, emphasis added)

When an author chooses to challenge the “existing understanding of the period,” in either large or small matters, they do, as Milan has acknowledged, “throw more people out of the story, and they will object” but, she argues, this is necessary in order to ensure that the existing understanding of the period does not remain stationary: “repeatedly portraying this will shift how people view historical accuracy” (“Historical”). While the inclusion of a board clip does not radically challenge historical romance readers’ “existing understanding of the period,” the village of Wedgeford certainly may.

It Takes a Village to Raise Awareness

With a population that is “only half white,” this “small village in rural England” would have been, as the novel acknowledges, “something of a rarity” (Milan The Duke ch. 9). Wedgeford is, however, a Wedgelot, because although the Chinese

community was fairly small […] it was significant. According to the census returns for 1881 there were 665 Chinese-born ‘aliens’ in England and Wales and a sixth of these lived in London, […] at the heart of London’s Docks. (Gray 84)

These were not merely transient sailors:

A Chinese quarter had developed by the 1880s in the Limehouse district. It consisted of two narrow streets, Pennyfields and Limehouse Causeway. Here the Chinese established grocery stores, laundries, restaurants and seamen’s hostels, catering for the needs of the Chinese crews in port. (Shang 89)

Milan was clearly aware of the location of this Chinese community, since there is a reference in the novel to “the Chinese mercantile exchange near the docks” in London (Milan The Duke ch. 12).

Since “censuses before 1991 recorded only country of birth and ignored ethnic origin,” some of the residents recorded in the census as having been born in China may have been “of non-Chinese ethnic origin” but, on the other hand, the census figure would not have included as Chinese either “people of Chinese ethnic origin born in Britain to immigrants” (Benton and Gomez 50) or people like Chloe, “born in Trinidad” (Milan, The Duke ch. 2), who are “ethnic Chinese from British colonies” (Benton and Gomez 50). Wedgeford, where Chloe’s is “not the only Chinese family, not even the only Hakka family” (Milan, The Duke ch. 2), is an invention of Milan’s, but given that there were Chinese immigrants in England in the 1880s and 1890s, and given that London’s Chinese community had clustered together, it does not seem totally implausible to imagine that, in the circumstances outlined by Milan, a small satellite Chinese community might have grown up in a village in Kent, a county which borders Greater London.

These circumstances are that the village had fallen into decline because it was originally “on a minor stage route,” and first

one of the stage routes ended, killed by the railways, followed by the other. […] The shops closed, and families who had lived here for centuries began to leave too, searching for work. […]

Then Mr. Bei and Mr. Pang had arrived. […] Mr. Bei had been in service with a merchant, but a shoulder injury prevented him from working his way home. They’d been wandering the countryside, looking for work. […] Wedgeford had been mostly empty. Its aging vicar had looked about, shrugged, and said that there were houses and there was land, such as it was. Mr. Bei and Mr. Pang were Hakka—a people that had been farming desolate hillsides in China for longer than the Church of England had existed.

After that, once Wedgeford had been established as a place of refuge when someone would end up stranded in England for some reason—nursemaids brought from foreign countries and tossed out after the children went away to school, or sailors pressed into service and let out in Bristol—they’d sometimes hear of Wedgeford.

That had been all it took for Wedgeford to flourish again. (Milan, The Duke ch. 9)

The references to sailors and, in particular, to “nursemaids brought from foreign lands and tossed out” may imply that one or two of the “at least five separate languages with multiple dialects” Milan, The Duke ch. 9) spoken in Wedgeford are from India. From “about the middle of the nineteenth century […] every year, in response to the needs of the labour market, thousands of sailors and hundreds of ayahs [nannies or nursemaids]” arrived in Britain “directly from the Indian sub-continent” (Visram 44). More than a few of these ayahs did meet the fate described by Milan, since

Return passages, formally agreed in India, were not always honoured, and ayahs were stranded. […] Attention was first drawn to their plight in 1855 when it was reported that 50-60 ayahs were found in one disreputable lodging-house in […] London’s East End. […] Victorian paternalism combined with the moral imperative to rescue the heathen other […] led to the establishment of a hostel for the ayahs, references to which first began to appear in 1891. (Visram 51)

Since the novel is set in 1891, it does not seem implausible that in earlier years some of these ayahs who had been “tossed out” might, had it existed, have found refuge in Wedgeford.

Wedgeford is diverse, certainly, but Jeremy’s shorter version of its history also emphasises that it should not be seen as exceptional: “Wedgeford happened the same way every other village in England ever happened. People stayed. That’s all” (Milan, The Duke ch. 9). His response suggests that diversity should be seen as a part of the reality of British history, no more worthy of being mistaken for a Widgelot than white characters and their villages.

In addition, the depiction of Chloe and her family challenges stereotypes about Chinese culture. These stereotypes have had a profound impact on Milan, not least because of the contents of the ethics complaints against her which were sent to the Romance Writers of America in 2019 by Suzan Tisdale and Kathryn Lynn Davis. As Milan observed in her response to the complaints, “the primary conduct that Tisdale wants RWA to punish is that I, a half Chinese-American woman, spoke out against negative stereotypes of half Chinese-American women” (“Response” 1). Milan had publicly objected, on Twitter, to elements of one of Davis’s books, including a sentence stating that “In China, no woman was taught much more than cooking and sewing and the graceful art of pleasing her husband” and another in which Davis had a Chinese female character state that “we are demure and quiet, as our mothers have trained us to be” (Davis qtd. in Milan “Response” 6). Davis, who is white, argued that her expertise was greater than Milan’s because

I earned a BA in English and history […] and a Masters in History […]. My major fields of study were the British Empire and China […], I studied Chinese history intensely for over seven years. Its culture was indeed oppressive and restrictive to women. (Davis 4)

In this context, The Duke Who Didn’t can be read as a rejection of Davis’s claim to authority and an attempt to share more accurate knowledge of this area of history.

Milan has stated that the controversy had an impact on her “research for this book about where my heroine’s mother would have come from” (Lenker). Milan’s heroine is Hakka, as are Milan’s Chinese ancestors, and Milan has stated that when she

started doing some research […] it was so illuminating to me in terms of discovering where my grandmother came from. I always thought her to be a full anomaly. But the Hakka people believed that Hakka women, in general, took on more male roles and were given a lot more responsibility. In 1850, there was a man who was Hakka who started, essentially, leading a rebellion. It was a massive civil war in China. But one of the tenets [of the rebel government] was that men and women were equal. I hadn’t really known any of that cultural background. (Lenker)

Milan, who had stated that “The notion of the submissive Chinese woman is a racist stereotype which fuels higher rates of violence against Asian women” (“Response” 7), therefore provides her readers with antidotes to the stereotype in her “intimidating, determined” (Milan, The Duke ch. 12) heroine and that heroine’s mother, who was “a Deputy Chancelloress of the Winter Department” and “could do anything; she usually did” (Milan, The Duke ch. 2). Further details which counter the stereotype can be found in the author’s note at the end of the novel.

A Feast with a Very British Sauce

In addition to countering mistaken ideas about the Chinese, the novel raises questions about the British and Britishness. It does so, appropriately for a carnivalesque novel, through Mr. Fong’s sauce, which is launched during the Trials. According to Bakhtin, feasts are “linked to moments of crisis, of breaking points in the cycle of nature or in the life of society” (9). Mr. Fong’s sauce (served as seasoning for a bao, “a pork bun” [Milan, The Duke ch. 17]), is a compact version of a feast; the competition it poses to an established sauce, White and Whistler’s Pure English Sauce, can be read as a culinary challenge to prevailing ideas about Britishness. Mr. White and Mr. Whistler became purveyors of the first sauce Mr. Fong developed: they wholly appropriated it after they “tossed him out with no money,” took “the sauce he’d left behind in the barrel, used the instructions that they had written out as he worked, and […] made a fortune” (Milan, The Duke ch. 2). This is, indeed, an English sort of “sauce” (in the sense of impudence): the stealing of the recipe replicates colonialist knowledge-extraction practices, such as those of the East India Company, which

first relied heavily on the Indian expertise, used systems (of trading networks, financial institutions, administration, information gathering and transmission, etc.) that were already developed and in place, and simultaneously appropriated the “know-how” that made the operation of these systems possible. Then, the Company institutionalized the appropriated knowledge and thus used it to rebuild the particular system for its own purposes. Arguably, this can be seen as a general pattern in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries in colonial India. (Alamgir 430)

Mr. Fong then spent years perfecting a new sauce, “better, tastier, richer, more balanced” (Milan, The Duke ch. 2), a sauce which, he declares, “is British” (Milan, The Duke ch. 8), even “extremely British” (Milan, The Duke ch. 8).

Milan, however, is a US author and not a British one; it is possible that these assertions of Britishness have implications for her own time and place. Such a superimposition of contemporary US politics on a historical British background would certainly not be unprecedented: romance scholar Jayashree Kamblé has argued that in “Regency romances […] the space associated with the British aristocratic and gentrified world, its ballrooms and country estates, ‘becomes charged and responsive to the movements of time, plot and history’ as it is unfolding now for the United States” (166-167). She gives the example of Gaelen Foley’s Knight series, in which the war with Napoleon “lends itself to being read as an allegory, with Britain standing in for the United States, Napoleon for America’s enemies, the liberal Whig party for the less jingoistic Democrats, and the Tories for the Republicans” (70). The Duke Who Didn’t is set in the Victorian period rather than the Regency, but the fact that Milan, as discussed in her author’s note to the novel, has drawn on her own family history of immigration to the US in creating Wedgeford, suggests that, in this novel too, Britishness offers parallels with American identity.

The period in which Milan wrote her novel was one of increasing hostility towards Chinese Americans: having already experienced an increased “readiness of security agencies to view Chinese Americans as potential spies rather than loyal American citizens,” (Li and Nicholson 4-5) their security was further threatened by the global COVID-19 pandemic which led to “a spike in hate crimes against Asian Americans” (Li and Nicholson 5). In this context, Jeremy’s statement that since Mr. Fong’s sauce was “fermented here, […] made here […], this sauce is British. If this sauce is British, I am British, and my wife is British, and my children will be British” (Milan, The Duke ch. 19) can perhaps be read more broadly as an indication of how the nationality of human beings in general, not simply British ones, should be determined. Mr. Fong, it should be noted, considers Jeremy, who was “born in England,” (Milan, The Duke ch. 3) to be “British British. In most of the ways that matter” (Milan, The Duke ch. 2). By extension, Chinese Americans such as Milan are American Americans in most of the ways that matter and should not, as Jeremy instructs a young white visitor to Wedgeford, be constantly subjected to “prying questions” (Milan, The Duke ch. 9) from “everyone who was white […] like ‘where are you from?’ and ‘how did you get here?’” (Milan, The Duke ch. 9). Such questions have been asked of Milan herself repeatedly, and she understands them as attempts to deny her the status of an American American:

I hear the words “originally from” a LOT in the “where are you from” context and people use it EVEN WHEN I explicitly mention my place of birth.

“Where are you from?”

“Southern California.”

“No, where are you FROM.”

“I was born in Southern California.”

“YOU KNOW WHAT I MEAN, where are you ORIGINALLY from?!”

For racists, the origin of white people is wherever they claim it is, but the origin of nonwhite people can only ever be the place where their ancestors lived, no matter how many generations back that was. (“I am”)

Milan, then, has both drawn on her own experiences and carried out primary historical research in order to use “the past as a crucible to explore the present.” Albeit in a carnivalesque manner, The Duke Who Didn’t raises extremely serious questions about racism and the existing norms of historical romance. While Milan is not alone in challenging some of these norms, The Duke Who Didn’t makes an important contribution to the body of works which can be read as advocates for change. It should, indeed, be ranked among the romances recognised “as novels of ideas […] sites of readerly and authorial thinking and communal debate” (Selinger 298-299).

Works Cited

Alamgir, Alena K. “‘The Learned Brāhmen, Who Assists Me’: Changing Colonial Relationships in the 18th and 19th Century India.” Journal of Historical Sociology vol. 19, no. 4, 2006, pp. 419–446. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6443.2006.00291.x

American Stationer. The American Stationer vol. 28. 3 July 1890. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433090916952&view=1up&seq=15

Appleton. D. D. Appleton & Company’s Illustrated Trade List of Domestic and Foreign Stationery. New York, 1869. https://archive.org/details/illustratedtrade01appl

Bakhtin, Mikhail. Rabelais and His World. Translated by Hélène Iswolsky, Indiana University Press, 1984.

Benton, Gregor and Edmund Terence Gomez. The Chinese in Britain, 1800-Present: Economy, Transnationalism, Identity. Palgrave Macmillan, 2008.

Catherine Heloise. “Book Review: The Duke Who Didn’t by Courtney Milan.” Smart Bitches, Trashy Books. 23 September 2020. https://smartbitchestrashybooks.com/reviews/the-duke-who-didnt-by-courtney-milan/

Davidson, MaryJanice. Danger, Sweetheart. Piatkus, 2016.

Davis, Kathryn Lynn. “Formal Complaint: Part 1.” 2019. https://www.docdroid.net/uMizS30/kathryn-lynn-davis-formal-rwa-complaint-pdf . This is also available via https://www.rwa.org/Online/News/2020/Audit_Documents.aspx and directly as a document in a zip folder from https://imis2.rwa.org/web/images/rwa/RWAFiles/files/Pillsbury_Audit_Report/Attachments_Tisdale_and_Davis_Complaints_Milan_responses_Ethics_Committee_Report.zip

Emgeeze, “What an anachronistic, boring mess…” Amazon customer review. 29 September 2020. https://www.amazon.com/gp/customer-reviews/R1BA8FJLP9KONO/ref=cm_cr_arp_d_rvw_ttl?ie=UTF8&ASIN=B08L8772DQ and archived here https://web.archive.org/web/20210318032604/https://www.amazon.com/gp/customer-reviews/R1BA8FJLP9KONO/ref=cm_cr_arp_d_rvw_ttl?ie=UTF8&ASIN=B08L8772DQ

Finston, Rachel. “Desert Isle Keeper: The Duke Who Didn’t.” All About Romance, 2 October 2020. https://allaboutromance.com/book-review/the-duke-who-didnt-by-courtney-milan/

Gray, Drew D. London’s Shadows: The Dark Side of the Victorian City. Bloomsbury, 2013.

Hackett, Lisa J. and Jo Coughlan. “The History Bubble: Negotiating Authenticity in Historical Romance Novels.” M/C Journal, vol. 24, no. 1, 2021. https://doi.org/10.5204/mcj.2752

Hallock, Jennifer. “History Ever After: Fabricated Historical Chronotopes in Romance Genre Fiction.” Paper presented to the 2018 IASPR conference. http://www.jenniferhallock.com/2018/06/27/history-ever-after-iaspr-2018/

Kamblé, Jayashree. Making Meaning in Popular Romance Fiction: An Epistemology. Palgrave Macmillan, 2014.

Knight, Edward H. Knight’s New Mechanical Dictionary. Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1884. https://archive.org/details/knightsnewmechan00knigrich/page/113/mode/1up

Lenker, Maureen Lee. “Romance author Courtney Milan reveals new cover, reflects on RWA implosion.” Entertainment Weekly, 24 August 2020. https://ew.com/books/courtney-milan-reveals-new-romance-cover/

Li, Yao and Harvey L. Nicholson Jr. “When ‘model minorities’ become ‘yellow peril’—Othering and the racialization of Asian Americans in the COVID-19 pandemic.” Sociology Compass, vol. 15, no. 2, 2021, pp. 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12849

Luther, Jessica. “Courtney Milan on Feminism and the Romance Novel.” Shondaland. 27 February 2018. https://www.shondaland.com/inspire/books/a16752742/courtney-milan-on-feminism-and-the-romance-novel/

Milan, Courtney. “Also for the record.” Twitter thread. 22 July 2020. https://twitter.com/courtneymilan/status/1286022674280398849

Milan, Courtney. “Fairytales of meritocracy.” Courtney Milan’s website. 15 December 2010. https://www.courtneymilan.com/ramblings/2010/12/15/fairytales-of-meritocracy/

Milan, Courtney. “Historical accuracy.” Twitter thread. 27 December 2018. https://twitter.com/courtneymilan/status/1078369352871624704

Milan, Courtney. “I am.” Twitter thread. 14 July 2019. https://twitter.com/courtneymilan/status/1150414019355787264

Milan, Courtney. “If you’re wondering.” Twitter thread. 31 August 2020. https://twitter.com/courtneymilan/status/1300491821504577536

Milan, Courtney. “I’ve hit the point.” Twitter thread. 18 August 2020. https://twitter.com/courtneymilan/status/1295739540909350912

Milan, Courtney. “Response to Suzan Tisdale Complaint.” 2019. https://www.docdroid.net/v0hn3eA/tisdale-response-pdf This is also available via https://www.rwa.org/Online/News/2020/Audit_Documents.aspx and directly as a document in a zip folder from https://imis2.rwa.org/web/images/rwa/RWAFiles/files/Pillsbury_Audit_Report/Attachments_Tisdale_and_Davis_Complaints_Milan_responses_Ethics_Committee_Report.zip

Milan, Courtney. “So the narrative structure.” Twitter thread. 22 July 2020. https://twitter.com/courtneymilan/status/1286016663972753408

Milan, Courtney. The Duke Who Didn’t. Self-published ebook, 2020.

Radway, Janice A. Reading the Romance: Women, Patriarchy, and Popular Literature. 1984. University of North Carolina Press, 1991.

Regis, Pamela. A Natural History of the Romance Novel. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2003.

Ryan, Claire. “The Implosion of the RWA.” Claire Ryan’s website. Post first published on 27 December 2019 but updated repeatedly up to 22 February 2020. https://claireryanauthor.com/blog/2019/12/27/the-implosion-of-the-rwa/

Selinger, Eric Murphy. “Literary approaches.” The Routledge Research Companion to Popular Romance Fiction, edited by Jayashree Kamblé, Eric Murphy Selinger, and Hsu-Ming Teo. Routledge, 2021, pp. 294–319.

Shang, Anthony. “The Chinese in London.” The Peopling of London: Fifteen Thousand Years of Settlement from Overseas, edited by Nick Merriman. The Museum of London, 1993, pp. 88–97.

Shaw, Adrienne. “The Tyranny of Realism: Historical Accuracy and Politics of Representation in Assassin’s Creed III.” Loading…, vol. 9, no.14, 2015, pp. 4–24. https://journals.sfu.ca/loading/index.php/loading/article/view/157

Stam, Robert. Subversive Pleasures: Bakhtin, Cultural Criticism, and Film. The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1989.

Stocker, Bryony D. “‘Bygonese’—Is This Really the Authentic Language of Historical Fiction?” New Writing, vol. 9, no. 3, 2012, pp. 308–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790726.2012.693094

United States Patent Office. Official Gazette. 4 November 1884. https://archive.org/details/officialgazette28unit/page/n935/mode/1up

Visram, Rozina. Asians in Britain: 400 Years of History. Pluto Press, 2002.

Willingham, A. J. “A romance novelist accused another writer of racism. The scandal is tearing the billion-dollar industry apart.” CNN, 14 January 2020. https://edition.cnn.com/2020/01/13/us/romance-writers-association-rita-awards-novel-scandal-trnd/index.html