The recent calls for #WeNeedDiverseRomance and #OwnVoices have created some change but not enough regarding the representation of people of color in the industry and in the books. Black romance authors are still tasked with working outside of the center and in the margins to create and find success. How did the pioneering Black cisgender heterosexual romance writers survive in this industry? Through the case of Brenda Jackson as the author brand and her novels, I propose that the authors (who did not have access to the financial and social capital most white authors had) were boxed out from the traditional social capital that white authors had. Instead, Brenda Jackson and other authors used the markers of cultural community wealth to build and maintain authentic relationships with readers and to create culturally resonant brands.

Positionality

I come to this project as a romance reader and romance writer, but primarily I am a qualitative communication researcher who is more interested in talking to people and interrogating how brands and organizations manage the relationships that allows them to exist and thrive in society. Under most conditions, my research is not fixated on critical literary studies or genre and textual semiotics. Therefore, this essay might differ greatly from what is expected. It is my opinion that this positionality creates a unique perspective for both theoretical and methodological stances. The perspective that I use for this research is a bifocal lens of critical race theory and communication, and the theoretical frameworks that organize this essay are organizational-public relationships, social capital, and community cultural wealth. This research essay is a mash-up or a “mixtape” that combines the loves of my multi-hyphenate nature (romance reading, romance novels, critical race theory, and communication strategy) yet also requires me to delve into fields beyond my training (Tinsley 16). Within this case study, I will incorporate autoethnographic interludes, interviews with my mother, interviews with Brenda Jackson (conducted by Dr. Julie Moody-Freeman), and sociological and communication theory. In this essay, I will employ “community cultural wealth” as the lens to show how Brenda Jackson as the author and Brenda Jackson as the brand/organization uses six forms of capital to radically transform how we examine the spaces occupied by Black romance authors.

Authors as Authors, Authors as Brands and Small Business Entities

A common refrain in writing circles is that writing is a business. For those who are and want to be more than a hobby writer, regardless of publishing status, one must invest time, talent, and money into the writing part of the job and the marketing of their books. Multiple authors and consultants – through conversations, blog posts, tweets, conferences, articles, podcasts, and books – exhort this point. Podcaster and science-fiction author Joanna Penn argued that the business mindset is necessary for authors who want to take their writing careers to the next level and asks authors to “reframe business as creative” (location 186 out of 317, Kindle). Golubov offered a critical-cultural take on the author-as-small business, which provided this clear description of the entrepreneurial author:

…this entrepreneurial author figure is urged to assume responsibility for her writing self as a project and as an object, actively self-reliant and self-determining, engaged in a continuous process of production of the self required by the dynamic nature of the genre (131).

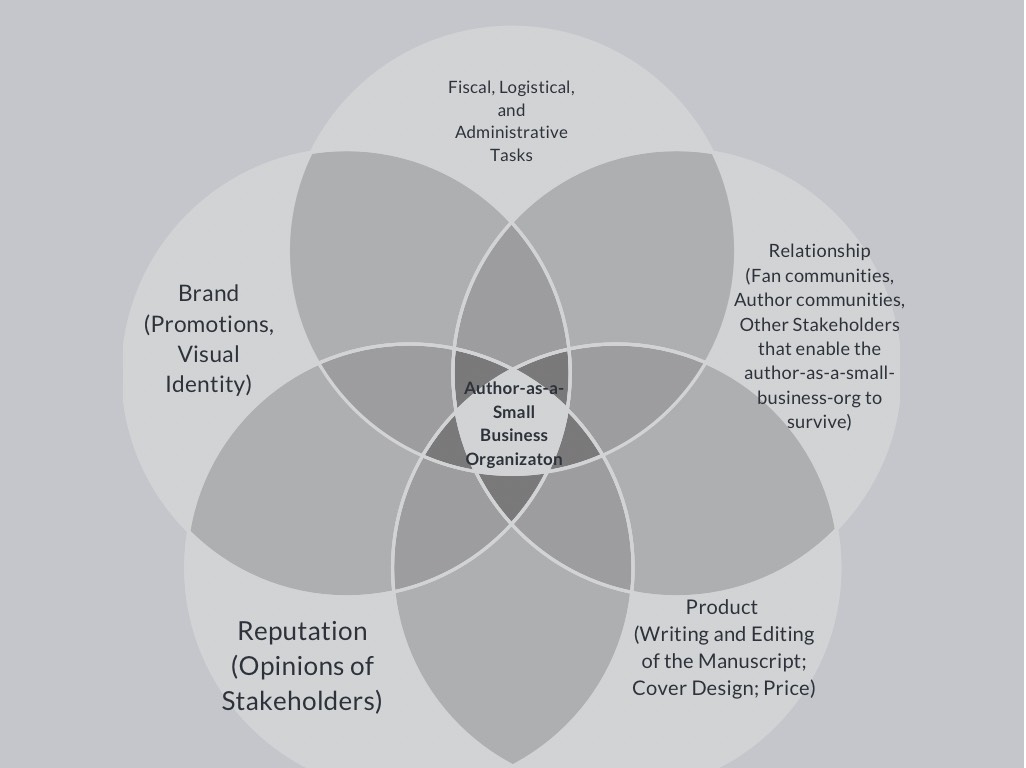

The author-as-a-small-business entity pivots the idea of the author as the word slinger to the concept of a creative who take responsibility for the multiple functions of their enterprise. Whether the author does them by themselves or if the author hires an assistant or other employees, the small business entity has to deal with the functions of business:

- logistics and distribution (e.g., publishing dates, doing wide distribution to all outlets)

- fiscal matters (e.g., taxation, price, salaries)

- product production (e.g., writing, editing, and formatting of the text)

- branding and other marketing (e.g., visual design, promotions)

- relationship management and other public relations functions (e.g., media tours, media releases, social media management)

Like any organization, authors must possess strategic branding, the requisite marketing tactics, a viable brand identity, a solid reputation, and relationships with readers and other stakeholders to be successful. Like many organizations, brand is often flattened into and equated with reputation, relationships, and small business enterprises. However, these are distinct yet interrelated entities. Yet, many authors sink money into logos and websites without truly knowing what a brand does, how the brand functions, or why relationships and reputation matter as well.

A complex, nuanced constellation of definitions for the construct known as branding exist. For this circumstance, I use this definition from Aaker:

A brand is a distinguishing name and/or symbol (such as a logo, trademark, or package design) intended to identify the goods or services of either one seller or a group of sellers, and to differentiate those goods or services from those of competitors. A brand thus signals to the customer the source of the product, and protects both the customer and the producer from competitors who would attempt to provide products that appear to be identical (7).

Authors occupy two realms in the creation of a brand: the business owner (or what I call the author-as-a-small-business) who owns the brand name and symbols, and the content creator (who generates and provides the goods and services readers expect). A company (including the author-as-a-small-business entity) cannot exist on branding alone. Authors and other organizations need quality productions, reputation, and relationships to survive in the marketplace. Reputation, itself an amorphous term, can be distilled into this simple quip from Paul Argenti: “A company creates a brand and earns a reputation.” The author-as-a-small-business entity must devise and implement a feasible brand and deliver strong books that build and solidify the reputation. Both brand and reputation are the bedrock for the relationship between an organization and its public, and entities that craft and manage their reputations in a deliberate, strategic fashion may have stronger relationships with their audiences (Fombrun and Rindova, 1998).

Understanding Relationships (from a Communication Perspective)

Once upon a time not long ago, the strategic communication and the public relations fields only looked at formal corporations and nonprofits as legitimate organizations worthy of study. Thanks to research projects such as Hutchins and Tindall (2016), a pivot is happening. Understanding how individual entities and popular culture franchises create brands, enable participatory culture, maintain fans, and propel anti-fans provides nuanced analysis and examples of how branding and fandom work on micro-levels.

All brands and organizations, whether they are individuals writing for AO3 or if it is a Fortune 500 behemoth, must consider their relationship with their publics or stakeholders. Rawlins (2006) distinguished publics and stakeholders this way: “organizations choose stakeholders by their marketing strategies, recruiting, and investment plans, but publics arise on their own and choose the organization for attention” (2). For this research paper, I will use both interchangeably since hybrid, self-published, and traditional authors have an ideal stakeholder group and manage fans and anti-fan publics who have been created and choose to interact with the author.

My approach to understanding public relations is informed by Kruckeberg and Starck (1988), who felt that public relations should be the “active attempt to restore and maintain a sense of community” (xi). Multiple definitions of organization-publics relationships exist. I lean toward simplicity, thus, my guide in understanding relationships in general and the relationships that romance authors have to establish and sustain to have a viable career is offered by Tomlinson: “a set of expectations two parties have for each other’s behavior based on their interaction patterns” (178).

Relationships are the bread-and-butter component of public relations. Ferguson first outlined the idea of relationships as foundational to the organization’s credibility and sustainability with its audiences and argued that researchers should prioritize this concept. Hon and Grunig noted that reputations are built based upon the behavior of the organization and how the publics interpret, understand, and interact with the organization, both currently and historically:

…all of these relationships are situational. That is, any of these relationships can come and go and change as situations change. Finally, these relationships are behavioral because they depend on how the parties in the relationship behave toward one another. Organizations do not have an ‘image’ or ‘identity’ separate from their behavior and the behavior of publics toward them. Instead, organizations have a ‘reputation’ that essentially consists of the organizational behaviors that publics remember (13).

The layered outcomes of a healthy relationship between a brand/organization and its audience must include trust, satisfaction, control mutuality, and commitment. Social capital can only be built through trusting relationships (Ihlen; Putnam; Sommerfeldt; Strauss). Social capital is an intangible form of symbolic capital because its power resides in the relationships formed between and among people and groups (Taylor). The outcomes of relationships – trust, community norms, and information – are grounded in “a system of trusting and supportive interconnected” groups (Taylor 9). Not all social capital is deemed as good or carries the same heft (Edwards). Good social capital normally equates to the items that can be fulfilled easily through elite, largely white status and networks. Without personal links to unlock certain doors or ease certain paths, persons of color have a harder time breaking into and breaking through barriers.

Social capital and relationships

What I believe is missing is an examination of Black romance and how Black romance authors use social capital as a way to build community with readers and other authors, a method to gain access to the gated echelons of publishing (e.g., editors, agents), and the function that places authors of certain identities in the marginalia of the industry. A popular research concept across multiple fields, social capital in its contemporary sense is an idea that arose from two scholars. Coleman posited that social capital functions as “a variety of entities with two elements in common: they all consist of some aspect of social structures, and they facilitate certain action of actors – whether persons or corporate actors – within the structure” (302). Bourdieu (1986) defined social capital as “the aggregate of the actual or potential resources which are linked to the possession of a durable network of more or less institutionalized relationships of mutual acquaintance or recognition” (248-249). As Lin proposed, social capital is created through the investments an entity makes to procure and receive expected returns in the marketplace.

Within the three definitions, the communicative aspects of relationships are embedded. Unless the intangible and tangible attributes of social capital are communicated and agreed upon, the relationship does not exist; communication builds the context for social capital and eventually relationships. Hazleton and Kennan found that for organizations to produce positive social capital, an organization or brand must engage in appropriate communication behaviors to enhance their relationships (“Social Capital”; “Internal Public Relations”).

The connective tissue between relationship management theory, branding, and fandom are social capital and cultural capital. Both forms of capital are the connector that allow for the creation and maintenance of fan community and author-fan relationships. For Black romance authors who are building and trying to woo Black readers, they must access and engage different forms of social capital to build linkages to their reader communities (also known as fans). These fan communities are seeking authenticity from the authors and their texts, and the author must use various forms of capital in their writing and in their presentation of self (or branding) for the relationships to grow and flourish. Using Brenda Jackson’s novels and her experience as a prism, I advocate that Black romance authors and their fandoms are created using the cultural community wealth model.

Cultural Community Wealth

Community cultural wealth is the critically based challenge to traditional ideas of cultural and social capital. Embedded within the community cultural wealth model are intersecting matrices of cultural talents, abilities, contacts, and intelligence grounded in the lived experience of being a member of a marginalized community that has survived and resisted micro-, meso-, and macro-aggressions (Saathoff; Braun). Yosso counters Bourdieu’s constructions of social capital, framing his work as being defined by white, middle-class values and focused on income and socioeconomic status. Yosso identified six types of community cultural wealth (“Whose Culture Has Capital?”):

- “Linguistic capital refers to “the intellectual and social skills attained through communication experiences in more than one language and/or style” (78).

- Familial capital is the “communal bonds” and cultural knowledge that inform one’s understanding of community history, cultural memory, and kinship.

- Social capital builds bridges and bonds that allow for the solidification of relationships and accessible networks. These networks include peers, social contacts, and community resources, for emotional support to navigate institutions.

- Navigational capital includes the skills to traverse through and within social institutions such as publishing or schools.

- Aspirational wealth is the ability to keep and follows one’s hopes and dreams despite barriers, both real and perceived.

- Finally, resistant capital refers to the knowledge and skills fostered through oppositional behavior that challenges inequality” (80).

Examining Brenda Jackson’s Journey through Romance

Community cultural wealth provides a larger framework of assets that marginalized groups use to navigate the publishing industry. Together, these concepts radically transform how we examine the spaces occupied by Black romance authors. Every instance of capital is not accessed or used by Jackson.

Linguistic capital as an author

Jackson in her personal interview expressed that writing was an interest from an early age. She wrote short love stories that her classmates gobbled up.

I started writing romance when I was in the eighth grade. Oh, I started writing love stories and again out of a need that was not met. I’m from Florida. And there was always every summer, these Marie Funicello and Frankie Avalon beach movies that came on TV. And then I’m like, wow, they don’t even have any Black friends at all. Why aren’t there Black people on American Bandstand? There were not. So I said, Okay, I’m going to entertain my classmates by writing short 10-page love stories (Jackson, personal communication, undated).

Across more than 20 novels, Jackson has shown her storytelling prowess and has integrated authentic components of African-American life and aspirational goals into her stories. Within this component of community cultural wealth, storytelling traditions of one’s culture are embedded, as well as the ability to communicate through art, dance, and poetry. Without adept storytelling, romance novels would not have the ability to transport readers, and without the ability to craft a narrative with the elements of authenticity and transportation, no writer of romance would have a career.

Familial capital as an author

Jackson accomplishes this through the tight, large congregations of characters related through ancestry or choice. These characters who orbit around the main characters and build a universe serve as mirrors, confidantes, friends, mentors, consiglieres, and counselors. For example, in the multiple-book series featuring the universes of the Madarises, Westmorelands, and Steeles, family is the crux of these characters’ worlds. Family provides shared outlooks, dreams, and expectations, and the realness of those features in Jackson’s books makes the characters align with the middle-class longings and realities of Black readers. They too are mentors with Big Brothers Big Sisters, high-level executives, entrepreneurs, members of social sororities, and community volunteers. In her first family, the parents (Jonathan and Marilyn) are of good caliber who expected their children to do the right thing and be socially active, and the sons did just that. In the first book Jackson ever released, Tonight and Forever, Justin helps with the Children’s Home Society with the boys and takes them camping; later, his brother Clayton was part of the Big Brothers organization. Thus, both sons were living out the Bible verse “to whom much is given much is required.” This family orientation echoes Jackson’s personal commitments as a sister, cousin, aunt, and wife. She crafted her romances to include messages of respectability and responsibility regarding community, romance, and safe sex.

Social capital as an author-as-a small business

Social capital is the idea that value rests within relationships (Strauss). Within her novels, Jackson deploys wide social networks for her characters. They are members of complex networks filled with kin, business associates, and friends who support, challenge, love, and protect each other. Jackson as a writer has also used social networks to find readers and create a loyal fandom for her novels. I am a personal witness to this in action via our sorority connection.

During the 1990s and 2000s, the one place I loved venturing to was Books For Thought, a small Black female-owned bookstore in Temple Terrace, Florida. (Sadly, the store closed after the owner died.) Closer to the University of South Florida, which was on the penultimate exit if leaving Tampa, the bookstore was a hub of Black thought and inspiration. I first heard E. Lynn Harris and bell hooks in this bookstore; this bookstore was a community hub for the Black community of the Tampa Bay area. People made treks from Sarasota, St. Petersburg, Tarpon Springs, and other points to attend book clubs, author events, and just hang out. Whenever we came into the store, Felicia would tell us eagerly about the newest releases, the new authors, and the upcoming author signings. She did not care who the authors were as long as they were creating quality material, and Black romance authors always had shelf space and respect in her shop. My mother and I came there eagerly to get new books and to meet the Black authors we always read. For several years, at our biannual sorority conventions, I would man Felicia’s booth and help her host authors. Every convention I worked, I remember helping line up the tables and watching my (soon-to-be) sorority sisters line up to speak with Brenda Jackson (a member of our sorority), take their photos, and sign their books. People were excited to see a Black author writing Black characters that resonated with them, especially after incidents where Black readers read and loved books that appeared to have Black authorship but did not. Over the years, Jackson and other Black fiction authors used the network of reviewers, Black bookstore owners, and social community groups to find readers (and eventual fans) and success. Even with limited support from their publishers, they were buoyed by Black book clubs, mentions in the Black press (including the best-seller list compiled by Essence magazine), and other kinship opportunities. Even recently, the nurturing of those social networks pop up in conversation. When I sat in a sorority meeting recently, several of the Dears (older members) mentioned that they read Brenda Jackson and met her at the sorority’s national convention at a book signing; on Twitter, I find that fellow professors who are my age were fans of Jackson, had met her via the sorority or book club signings, and were saving to attend an upcoming fan cruise.

Navigational capital as the author-as-a-small-business

For many years, Black authors have navigated outside of the dominant structures of romance, yet they persisted because they believed in romance. For Brenda Jackson, romance has meant writing love stories that celebrate the same love she experienced with her husband, and finding her place in the canon required the grit, aptitude, and strength to continue despite the challenges she faced. Also, as a veteran of corporate America, Jackson knew how to navigate tight and very white spaces where professionalism was coded to mean white.

As Edwards noted in her examination of communication practitioners of color, “[e]ntry takes longer and more work, and they are likely to have to justify their position in a way unnecessary for white colleagues…” (5). Regardless of the profession, this statement rings true for many professionals of color, especially Black women in the creative industries. This is a parallel to the treatment Black authors in romance have received. As an unpublished author in the 1990s and early 2000s, I remember speaking with other Black romance authors who told me to stick with it despite the publisher requests to whitewash the novels I was writing, and this thinking persists. To this day, publishers pushed the blame for not being able to accept and hire writers working on Black books onto the demographics of a certain, imaginary audience. Jackson knew that there was an audience for the romance fiction she was writing, books where heterosexual, cisgender Black couples were romantic, passionate, and caring and novels that captured the lives of middle-class families of educated Black men. And she was able to draw in readers who yearned and hoped for the same things.

Aspirational capital as an author

Resiliency is embedded within this aspect of community cultural wealth. Before Jackson was an author, she was a reader. Yet the world of romance that I entered into was different from the romantic fiction world Jackson started in. For me, the first two Arabesque Romance novels featuring Black characters and then Brenda Jackson were my gateway into romance representations that looked like the middle-class Black folks I knew – the lawyers and pharmacists and entrepreneurs that populated my world of church, Del-Teens, Jack and Jill, and the Links. My mother who had been an avid romance reader for years, experienced the same dissonance that Brenda Jackson did when she read romance: the absence of people who looked like them pulled them fully or partially out of the genre. Jackson in her interview said:

There were no African American romance writers…. I figured, that if modern-day romance could not show me. I really didn’t want to read it, you know. If it didn’t show people that looked like me, I really didn’t want to deal with it….I did not want to deal with reading a modern-day or contemporary that did not show at least neighbors or…friends… (Jackson, personal communication, undated).

Jackson continued to read some romances. My mother stopped, unimpressed with the tidal wave of 1980s romances because they didn’t engage or mesh with her life. It wasn’t until I came across those romances in the now-forgotten K-Mart on 34th Street that my mother reconnected with romance, and it wasn’t until she started to read Brenda Jackson that she became a devout romance reader and a fan of a romance writer. One day in the 1980s, my mother decided she did not want to read about any other white heroines and heroes, but now my mother has found romance novels that provide the cultural and historical resonance she wanted. The dreams and hopes motivated the drive to overcome, which is essentially resistant capital.

Resistant capital as an author

The “sticky floor” and “acrylic vault” metaphors are appropriate in addressing the early treatment of Black romance authors, and to some extent describe the current conditions that some authors have. Early in her career, Jackson believed her biggest challenge would be having a five book series:

As long as I can get one book [deal as] long as they know there are two others already written, it’s a five book series. So I thought that would be my hurdle, but it wasn’t my hurdle. My hurdle was the characters were black. That was the hurdle. If we, you know, and I’m sure a lot of publishers right now will not tell you some of the things they said to Black authors during that time that was very discouraging to us (Jackson, personal communication, undated).

Not only did she (as well as other authors) have to deal with publishers decrying and dismissing Black romance, there was also the issue of dealing with white authors within and outside of the Romance Writers of America:

And I was the only Black in the Romance Writers of America. I was the only Black in the group. I was a founding member of the Charter that formed up in Jacksonville. And so it was like me understanding their culture and them understanding my culture. Because a lot of things when they were, you know, read my work and critique it they would take it out, and I’m like no, that needs to go back in because that’s true, that’s happened, you know, and that one is part of my culture. And then when I read their work I would tell them, you need to put Black people in your book. We have white people in ours. Why can’t you put Black people in yours, but then when I read their book, there were a lot of stereotypes in there and words like when one of my lady writer friends would describe a Black girl, she would put her hair as nappy, and I’m like, where do you get that from? You could use curly not nappy, you know, and so I had to tell them about words that they thought were okay. No, that’s not okay! It was so messed up. So it was a learning lesson for both of us. … (Jackson, personal communication, undated).

She remembers working, revising, and editing her novels prior to 1995, when she was first published, and receiving diminishing responses from publishers. After taking classes at various romance conventions and from authors such as Nora Roberts and Linda Howard, Brenda Jackson rewrote her 100-page novellas into 200- and 300-page novels. Yet, the publishers didn’t want the books because the characters were Black:

And they would tell me that ‘we don’t have an audience for them’ or ‘if the publishing industry isn’t broken, why fix it? We have plenty of readers who are satisfied. Black women are satisfied reading our white books. So why would we change it or add it just for them?’ Then they would worry about the women in the Bible belt (Jackson, personal communication, undated).

Resistant capital as the author-as-a small business

The constant push to push through the invisible obstacles and persist despite sticky floors is a signal of the resilience that Jackson and other writers had. When Jackson launched her career with Tonight and Forever, her publisher refused to do the typical promotion push for her book:

(The publisher) only paid us half the amount the white author’s books were. Whatever their percentage was we got half of that. And we would have to pretty much promote our own book. They would print it for us and get it published (Jackson, personal communication, 2020).

Any author in this circumstance – having a first book within the second wave of widely published Black romance and without a publisher’s push – has to assemble the branding components that will allow for them to be seen and considered as well as building relationships and cultural capital that will amplify those efforts.

Conclusion

If we consider the industry as an obstacle course, Black authors are required to dodge and transcend multiple traps: racial stereotypes, socioeconomic barriers, and social capital blocks. In this case, Jackson’s implementation of the community cultural wealth model during the early years of her romance career assisted with her continued success with Black romance readers. By using the cultural touchstones in her work and being seen in Black spaces such as Black bookstores and conventions, she has demonstrated an ethic of care, concern, and love for her readers and her community, and that has helped her build a beneficial relationship with her audience. The foundations of that relationship are trust, satisfaction, and commitment modeled through the pillars of the cultural community wealth mode.

These six forms of cultural capital explain how African American/Black writers build careers and fandoms without abandoning cultural hallmarks or cultural identity and establish themselves outside of the traditional boundaries of the romance industry. Community cannot exist when the markers of social capital are missing and the relationships among the community members are not functioning. Black romance authors have relied upon the cultural wealth model to sustain, provide agency, and overcome. Without these elements, most authors from marginalized groups would not succeed in the lily-white publishing industry. Brenda Jackson used these elements to form a strong, bonded relationship with Black female romance readers and has managed to continue to hold onto that core constituency while building fans across the other demographics that publishers thought were not ready for Black romance.

Future research

I cannot pass up the opportunity to think about or discuss the next steps. The work should be considered generative; this essay should be a starting point for other research, not the terminal destination. Building on Yosso’s work, other researchers uncovered other areas of community cultural wealth. These elements can be included into an analysis or used to guide a qualitative research project. Also, this research should be replicated or reconsidered with authors who are not writing about cisgendered, heterosexual romance and with authors who are not themselves cisgender and/or heterosexual. Serious consideration should be given to the construction of author brands using community cultural wealth and social capital, the ongoing push-pull dynamics between fan communities and authors, and the relationship building and maintenance strategies.

Recommended Novels from Brenda Jackson

Tonight and Forever (Justin Madaris), Harlequin, 1st printing September 1995; 2nd printing December 2007.

Eternally Yours (Clayton Madaris), Harlequin, 1st printing October 1997; 2nd printing February 2008.

Fire and Desire (Trevor Grant, Madaris Series), Harlequin, 1st printing August 1999; 2nd printing January 2009.

References

Aaker, David A. Managing Brand Equity. Simon & Schuster, 1991/2009.

Bourdieu, Pierre. “The Forms of Capital.” Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, edited by John G. Richardson, Greenwood, 1986, pp. 241-258.

Braun, Derek C., et al. “The Deaf Mentoring Survey: A Community Cultural Wealth Framewor for Measuring Mentoring Effectiveness with Underrepresented Students.” CBE – Life Sciences Education, vol. 16, no. 1, Spring 2017, pp. 1-14.

Coleman, James Scott. Foundations of Social Theory, Belknap Press, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 1990.

Edwards, Lee. Power, Diversity and Public Relations. Routledge, 2014.

Ferguson, Mary Ann. “Building Theory in Public Relations: Interorganizational Relationships as a Public Relations Paradigm.” Journal of Public Relations Research, vol. 20, no. 4, 2018, pp. 164-178.

Fombrun, Charles, & Rindova, Violina. “Reputation Management in Global 1000 Firms: A Benchmarking Study.” Corporate Reputation Review, vol. 1, no. 3, 1998, pp. 205-215.

Golubov, Nattie. “Reading the Romance Writer as an Author-Entrepreneur.” Interférences littéraires/Literaire interferenties, vol. 21, “Gendered Authorial Corpographies”, edited by Aina Pérez Fontdevila & Meri Torras Francès, 2017, pp. 131-160.

Hazleton, Vincent, and William Kennan. “Social Capital: Reconceptualizing the Bottom Line.” Corporate Communications, vol, 5, no. 2, June 2000, pp. 81-86.

Hon, Linda Childers, and James E. Grunig. Guidelines for Measuring Relationships in Public Relations. Institute for Public Relations, 1999, https://www.instituteforpr.org/wp-content/uploads/Guidelines_Measuring_Relationships.pdf

Hutchins, Amber, and Natalie T.J. Tindall. Public Relations and Participatory Culture: Fandom, Social Media, and Community Engagement. Routledge, 2016.

Ihlen, Øyvind. “Building on Bourdieu: A Sociological Grasp of Public Relations.” Public Relations Review, vol. 33, no. 3, September 2007, pp. 269-274.

Kennan, William R., and Vincent Hazleton. “Internal Public Relations, Social Capital, and the Role of Effective Organizational Communication.” Public Relations Theory II, edited by Carl H. Botan and Vincent Hazleton, Routledge, 2006, pp. 311-338.

Kruckeberg, Dean, and Kenneth Starck. Public Relations and Community: A Reconstructed Theory. Praeger, 1988.

Lin, Nan. Social Capital: A Theory of Social Structure and Action. Cambridge UP, 2002.

Penn, Joanna. Your Author Business Plan: Take Your Author Career to The Next Level. Curl Up Press, 2020.

Putnam, Robert D. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. Simon & Schuster, 2000.

Rawlins, Brad L. Prioritizing Stakeholders for Public Relations. Institute for Public Relations, March 2006, https://www.instituteforpr.org/wp-content/uploads/2006_Stakeholders_1.pdf.

Saathoff, Stacy D. “Funds of Knowledge and Community Cultural Wealth: Exploring how Pre-Service Teachers can Work Effectively with Mexican and Mexican American Students.” Critical Questions in Education, vol. 6, no. 1, Winter 2015, pp. 30-40. ERIC, https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1051078.

Sommerfeldt, Erich J. “The Civility of Social Capital: Public Relations in the Public Sphere, Civil Society, and Democracy.” Public Relations Review, vol. 39, no. 4, 2013, pp. 280-289.

Strauss, Jessalynn R. “Capitalizing on the Value in Relationships: A Social Capital-Based Model for Non-Profit Public Relations.” Prism, vol. 7, no. 2, 2011, https://www.exhibit.xavier.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1065&context=communication_arts_faculty.

Taylor, Maureen. “Public Relations in the Enactment of Civil Society.” The SAGE Handbook of Public Relations, edited by Robert L. Heath, SAGE, 2010, pp. 5-15.

Tinsley, Omise’ eke Natasha. Beyoncé in Formation: Remixing Black Feminism. U of Texas P, 2018.

Thomlinson, T. Dean. “An Interpersonal Primer with Implications for Public Relations.” Public Relations as Relationship Management: A Relational Approach to the Study and Practice of Public Relations, edited by John A. Ledingham and Stephen D. Bruning, Lawrence Earlbaum, 2000, pp. 177-203.

Yosso, Tara J. “Whose Culture Has Capital? A Critical Race Theory Discussion of Community Cultural Wealth.” Race Ethnicity and Education, vol. 8, no. 1, 2005, pp. 69-91.